What's happening over the ditch?

The debate about electricity prices and other policy issues is often carried out in highly parochial terms. Often, though, similar debates are taking place elsewhere in the world and it can provide a useful perspective to compare the issues and outcomes in different jurisdictions. While each electricity industry has its own features and challenges, there is often a lot of commonality, particularly where the basic industry structure and regulatory framework is similar. In this light, it’s worth taking a break from the frenzy of Australian energy political debate to look across the Tasman Strait at our neighbours, New Zealand.

Below we take a look at an electricity price review underway in New Zealand and also consider how its retail market matches up with the market in Australia and the United Kingdom.

New Zealand’s Electricity Price Review

In New Zealand, the government has commissioned an electricity price review, to be carried out by an independent expert panel of advisors.

The Electricity Price Review has been commissioned “to investigate whether the electricity market, as it exists at present, is delivering a fair and equitable price to end-consumers”[i]. The Review “will consider whether the current electricity market and its governance structures will continue to be appropriate with rapidly changing technology and new innovations in the sector”[ii].

Background to the New Zealand review

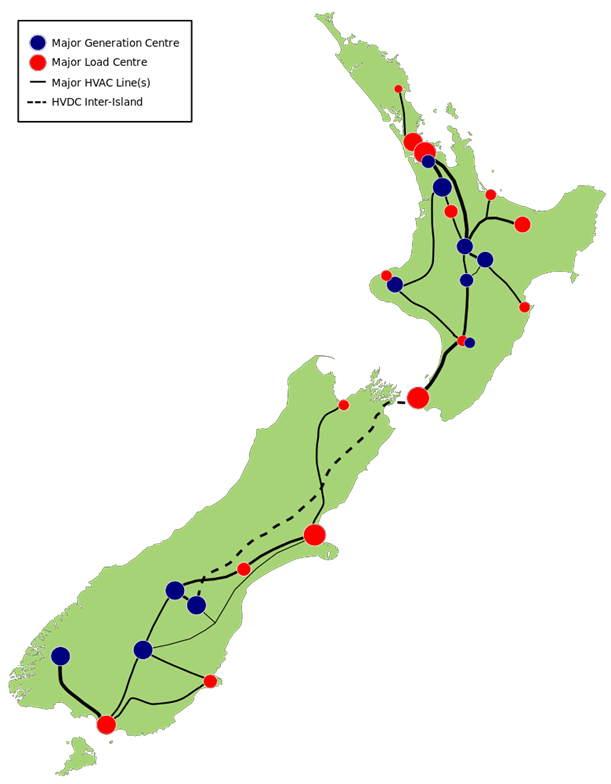

New Zealand’s electricity generation sector is dominated by dispatchable renewable plant: mostly hydroelectric and geothermal. Compared to other International Energy Agency (IEA) countries’ electricity systems, New Zealand has one of the highest proportions of such plant[iii]. New Zealand has some indigenous fossil fuel production but given the small amount of fossil fuelled plant, international gas and coal prices are not a major driver of wholesale electricity prices. There are some wind farms and a modest amount of rooftop solar PV. New Zealand’s two main islands are interconnected by a transmission line, but there is no connection to other countries. Annual consumption is around 39TWh[iv], spread across 2 million customers. Residential demand is a third of the total. Demand is higher in winter due to residential space heating requirements, as there is limited penetration of reticulated gas.

Figure 1: Map of New Zealand electricity system[v]

Up to the 1970’s, the New Zealand Electricity Department (NZED) owned and ran almost all the large-scale generation, the transmission network and carried out system operation. Local distribution systems and the retailing of electricity to users were managed by 69 local supply authorities. Between 1987 and 1999, the industry went through a major restructuring, including corporatisation and separation of the major generating units into four separate businesses, who now make up four out of the five large gentailers in the market. Transmission and system operation were separated out into Transpower. Meanwhile the local distributors were functionally separated into distribution and retail and a period of demergers and mergers resulted, with the distribution businesses becoming somewhat aggregated (there are now 29) and the retail businesses ultimately merging with generators. The restructuring allowed the introduction of competition into the generation and retail sectors, and new entrants soon joined the incumbents. In October 1996, the wholesale electricity market started trading while retail contestability was formally allowed from 1993. 2003, the Electricity Commission was established as the regulator for the New Zealand electricity industry. In 2010, the Commission was replaced by the Electricity Authority, and the Commission’s transmission approval functions were shifted to the Commerce Commission and the Ministry of Economic Development (now MBIE, and the department running the Price Review).

New Zealand has had relatively stable policy settings since it embarked on liberalisation. There have been two significant reform packages. In 1999, four independent generation companies were created from the Contact Energy assets. These businesses were permitted to vertically integrate, stimulating retail competition as they restructured as gentailers and competed against each other in both wholesale and retail markets.

In 2009, the market was reviewed, and some steps were taken to improve competition in the retail market by mandating physical and asset swaps between the generators in order to improve the geographic balance of the main gentailers[vi]. Distribution companies were also permitted to re-enter the retail market without restriction outside their own distribution service area and steps were taken to improve liquidity in the hedge market. Notably, all these reforms were market-oriented rather than trying to regulate the behaviour of market participants.

An Emission Training Scheme (ETS) was introduced in 2008 to help meet New Zealand’s Kyoto Protocol obligations. The stationary energy sector, encompassing electricity generation, was initially required to surrender one emission ‘unit’ for every two tonnes of CO2 emitted (or other equivalent emissions) from July 2010. A fixed surrender price of $25/tonne provided a cap on the costs, but in the event the price declined from $20 to $2 in 2014 before recovering to trade close to the cap price in recent years. Given the dominance of carbon free generation sources, the ETS has only had a limited impact on electricity prices. As a consequence, it is not controversial in the way climate policy has been in the Australian electricity sector.

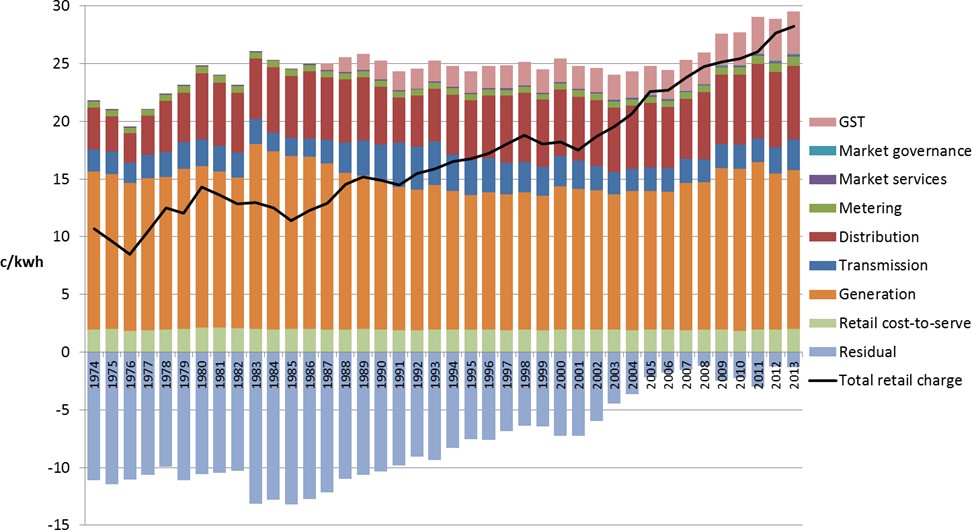

An unusual feature of the New Zealand market (and a factor in the concerns driving the Review) is that in the old NZED days, network charges were heavily weighted towards business users, with both large industrial and residential consumers contributing very little to these shared costs. This cross-subsidy has been gradually unwound, meaning that households have seen a material price rise over the years even though the underlying cost structure of the industry has not changed significantly. This is shown in figure 2 below:

Figure 2: New Zealand residential cost components (Real $2013)[vii]

How does New Zealand match up against Australia?

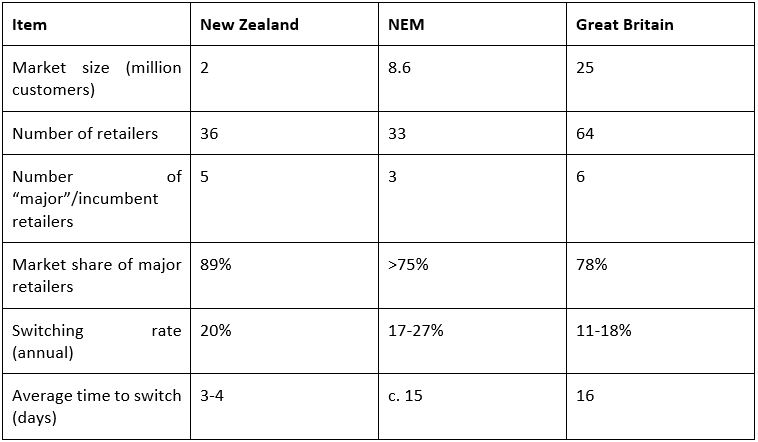

The Electricity Retailers’ Association of New Zealand commissioned my consultancy, Newgrange Consulting, to prepare the International Review of Electricity Retail Markets report: comparing three liberalised electricity retail markets - New Zealand, Australia’s National Electricity Market and Great Britain. A high level comparison of the three markets is shown below:

Table 1 High level metrics of each market [viii]

Some clear themes emerge from the comparison. All three markets covered in the report have high levels of switching by international standards. Switching is not the only indicator of effective competition, but it illustrates that there is genuine competitive tension and that retailers have to actively attract and retain customers to be successful. New Zealand’s What’s My Number campaign has assisted in delivering very high levels of awareness of the ability to switch and the value of doing so. New Zealand has the lowest time to switch of the three countries. In all three countries, a small number of large gentailers have the lion’s share of the market, but although not shown, in each case, new entrants are gradually increasing and capturing a greater share of the market.

Price dispersion is not shown in the table, but has emerged as a key concern across all three markets. Regulatory authorities don’t measure this metric in exactly the same way, but the gaps appear to be lower in New Zealand: while the Electricity Authority estimates the equivalent of up to $192 can be saved by switching to the lowest offer in the market, Ofgem’s figures for Great Britain are $703 and the ACCC’s maximum savings figure is $832 (South Australia). In all cases, analysis suggests that the lowest offers are around the marginal cost of the most efficient supplier, which is consistent with competition theory. Accordingly, retailers seek to recover their fixed costs and margin from other’ “stickier” customers. It follows that any attempt to constrain the extent of price dispersion will likely see the lowest offers disappear as well as the highest. After all, average margins are not especially high. As explained in a previous Energy Insider article, Ofgem’s reforms following its Supply Probe, intended to simplify customer choice by restricting suppliers to four tariffs for electricity supply for each payment method, resulted in lower switching rates and higher retail margins.

Although the impact of new technologies is a key concern of the NZ Price Review, the country is relatively well-placed to manage this. New Zealand is ahead of both Australia and Great Britain in its smart meter rollout, positioning it well for further innovation in retail services and the capacity to offer more cost-reflective tariff types, such as demand tariffs or time of use. The retailer-led rollout has been achieved without the sort of cost shock experienced in Victoria. Meanwhile, the take-up of rooftop solar and batteries have been fairly modest, given that New Zealand’s governments have refrained from offering generous subsidies for these technologies. So compared to Australia, in particular, there is time to observe the impact of growing penetration of these technologies and respond appropriately.

Conclusion

The issues in New Zealand’s electricity retail market are not as acute as in Australia or Great Britain: the cost drivers are not as significant, price dispersion (which is a normal outcome in a competitive market, but which attracts concerns around “fairness”) is not as great, customers are generally aware of the option to switch, prepayment is a cost-effective option, the take-up of new technologies by customers is modest, while smart meters have been successfully rolled out. Regulatory reforms in Great Britain and Australia have failed to achieve their goals: in Britain, tariff simplification failed to drive greater engagement and resulted in higher retail margins, while in Australia hardship policy has failed to stem a rise in disconnections. Meanwhile, New Zealand’s electricity system has been well-served by the competition-oriented reforms and limited government intervention to date.

The perennial concern that some households struggle to pay their electricity bills is of course legitimate. But is an outcome of multiple factors including general poverty levels, the welfare system, and the efficiency of the housing stock. It is not solved by heavy-handed retail regulation, which may even make the situation worse.

[i] New Zealand Electricity Price Review, First Report, 30 Aug 2018, https://www.mbie.govt.nz/info-services/sectors-industries/energy/electricity-price-review

[ii] ibid

[iii] IEA, 2017, Energy policies in IEA countries - New Zealand

[iv] Calculated using demand data at www.emi.ea.govt.nz

[v] Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation, 2017, New Zealand: Electricity Retail Services Market Reform, APEC Policy Support Unit

[vi] ibid

[vii] Electricity Authority, 2014, Analysis of historical electricity - Final Report

[viii] Electricity Authority, Ofgem, AEMC, Advisory Panel

Related Analysis

2025 Election: A tale of two campaigns

The election has been called and the campaigning has started in earnest. With both major parties proposing a markedly different path to deliver the energy transition and to reach net zero, we take a look at what sits beneath the big headlines and analyse how the current Labor Government is tracking towards its targets, and how a potential future Coalition Government might deliver on their commitments.

Navigating Energy Consumer Reforms: What is the impact?

Both the Essential Services Commission (ESC) and Australian Energy Market Commission have recently unveiled consultation papers outlining reforms intended to alleviate the financial burden on energy consumers and further strengthen customer protections. These proposals range from bill crediting mechanisms, additional protections for customers on legacy contracts to the removal of additional fees and charges. We take a closer look at the reforms currently under consultation, examining how they might work in practice and the potential impact on consumers.

International Energy Summit: The State of the Global Energy Transition

Australian Energy Council CEO Louisa Kinnear and the Energy Networks Australia CEO and Chair, Dom van den Berg and John Cleland recently attended the International Electricity Summit. Held every 18 months, the Summit brings together leaders from across the globe to share updates on energy markets around the world and the opportunities and challenges being faced as the world collectively transitions to net zero. We take a look at what was discussed.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.