The wildcat strike: Twenty years on

We are often discussing the great new challenges of securely operating a power system with new renewable and storage technologies. Twenty years ago the National Electricity Market (NEM) supply was much more uniform relying on conventional large power systems, predominately coal. But that was no cruise either as the power system then faced a routine threat as big as anything we face today, but which has now abated: industrial action.

Like elsewhere in Australian industry, power sector industrial relations were improving by the end of the twentieth century. The year 2000 saw something of a last hurrah in Victoria: firstly, extended lockouts and bans at Yallourn Power station, followed by the very memorable evening of 2 November 2000. “Wildcat” action across Victoria’s Latrobe Valley suddenly brought the power system to its knees, then, almost as quickly, resolved itself in the early hours of 3 November.

Twenty years on, we take a nostalgic look back at a night to remember.

Unions and the power system

The power industry was once plagued by industrial disputes that often led to power rationing and/or load-shedding. As there was one government employer, which is understandably very sensitive to electricity disruption, a small number of well-organised workers had tremendous bargaining clout and exercised it frequently.

For example, in 1989 Victorian government changes to workers’ compensation was opposed by the Victorian Trades Hall Council. The Council forced all industry to shut down on 25 July, regardless of their workforces’ views, simply by getting two power sector unions to restrict power station output[i]. Unit controllers didn’t actually walk out, which would be dangerous to plant and personnel, instead they co-ordinated to dispatch plants’ output to the level that forced the desired electricity restrictions to be imposed on the community. This rather contrived form of industrial action seems unthinkable now, but was commonplace in the pre-NEM era.

But threatening the power supply didn’t always work out for the unions: the great Queensland power strike of 1985[ii] was ultimately won by an aggressive Bjelke-Petersen government and permanently weakened power unions in that state. The government invoked a state of emergency, which applies extraordinary legal pressure on strikers. This very heavy-handed approach was claimed to be justified by the community impact of widespread power disruption.

The sector’s industrial climate improved greatly during the 1990s thanks to:

- The “Enterprise Bargaining” and “Protected Action” regime overseen by the Industrial Relations Commission (IRC); and,

- Disaggregation, and ultimately privatisation, of the industry which meant there was no longer one single, electorally-sensitive employer with whom to dispute.

Nevertheless in Victoria’s Latrobe Valley, always an industrial hotbed, unions remained active. This created a problem for generators and retailers in the market that had to be resolved before privatisation. If a strike shut down generators, spot prices would spike whilst retailers were relying on hedging contracts with those generators. To moderate this financial risk a complex arrangement of “Industrial Relations Force Majeure” (IRFM) was set up. This meant if a major industrial disruption extended beyond 24 hours, generators would be relieved of some contracts, and Victorian spot prices would be capped to a low level by the market operator. IRFM continued as a state derogation during the first years of the NEM[iii].

The result was that during an extended strike, power station owners would not be financially crippled. This arguably emboldened them to bargain harder than an elected government could.

Yallourn coal mine changes

The new private owners of Yallourn Power Station saw an opportunity to improve mine efficiency by changing from bucket wheel dredgers to bulldozers scraping the coal off a sloping surface (see photo). Dredgers are complex and extremely maintenance intensive, so bulldozers were much less costly. For the same reason, this change was hotly opposed by those who provided this maintenance, and in late 1999 workplace bans were affecting, but not stopping, Yallourn power station production.

In early January 2000 management brought the dispute to a head by locking-out the workforce, shutting down the power station and invoking IRFM. January was mild, so the power system carried on without Yallourn, but hot weather eventually arrived on 2 February and 800MW of load-shedding resulted[iv]. With a newly privatised industry, the young Bracks state government had little power system expertise to call on. To avoid further load-shedding, it imposed excessive electricity restrictions on the community. The demand restrictions were so excessive they created a supply surplus that was embarrassingly exported into other states[v].

The government ultimately felt it had no choice but to resolve the crisis through invoking its Emergency Services Act – an extraordinary act for a Labor government[vi]. This effectively forced the workers back under management’s terms and the power station re-started. The bulldozers were introduced and are mining coal to this day.

Figure 1: Bucket Wheel Dredger

Source: Energy Australia

Figure 2: Bulldozer slope mining

Source: Energy Australia

CFMEU wildcats

This apparent success of a hard-line management tactic infuriated unions, but there were now few legal options to express this – a reversal of many decades of unions’ strength in the industry. Union head offices realised that a widespread response would be “unprotected” in industrial law, exposing themselves and members to litigation. However the authority of the Construction Forestry Mining and Energy Union (CFMEU) was complicated by a rift with Latrobe Valley delegates[vii].

Meanwhile in the Valley anger about Yallourn festered through 2000.

Thursday 2 November was a mild spring day with plenty of Latrobe Valley generation operating, as was then common, Victoria was exporting surplus electricity to New South Wales and South Australia. During the afternoon a meeting of the CFMEU was held at the Morwell Bowling Club to discuss an IRC decision on Yallourn. The meeting resolved to ignore their union’s head office and take immediate action: known as a “wildcat strike”. The CFMEU represented most of the unit controllers at Yallourn, Hazelwood and Loy Yang A, who immediately began shutting down almost all the 4,000MW of generation the power stations had on-line at the time[viii].

Even in mild conditions, shutting down such a huge amount of generation without warning will create major disruption. The chaotic behaviour showed how much the previously stage-managed industrial processes had broken down. It is possible the system could have collapsed entirely had National Electricity Market Management Company (NEMMCO) staff not successfully pleaded with unit controllers to slow the wind back.

Meanwhile peaking generators scrambled to replace the shortfall. But this was not quick enough, load shedding was required for the second time that year[ix] and Victorian and South Australian prices reached the price cap, $5,000/MWh. And, because it happened so suddenly, the 24-hour IRFM notice could not be exercised.

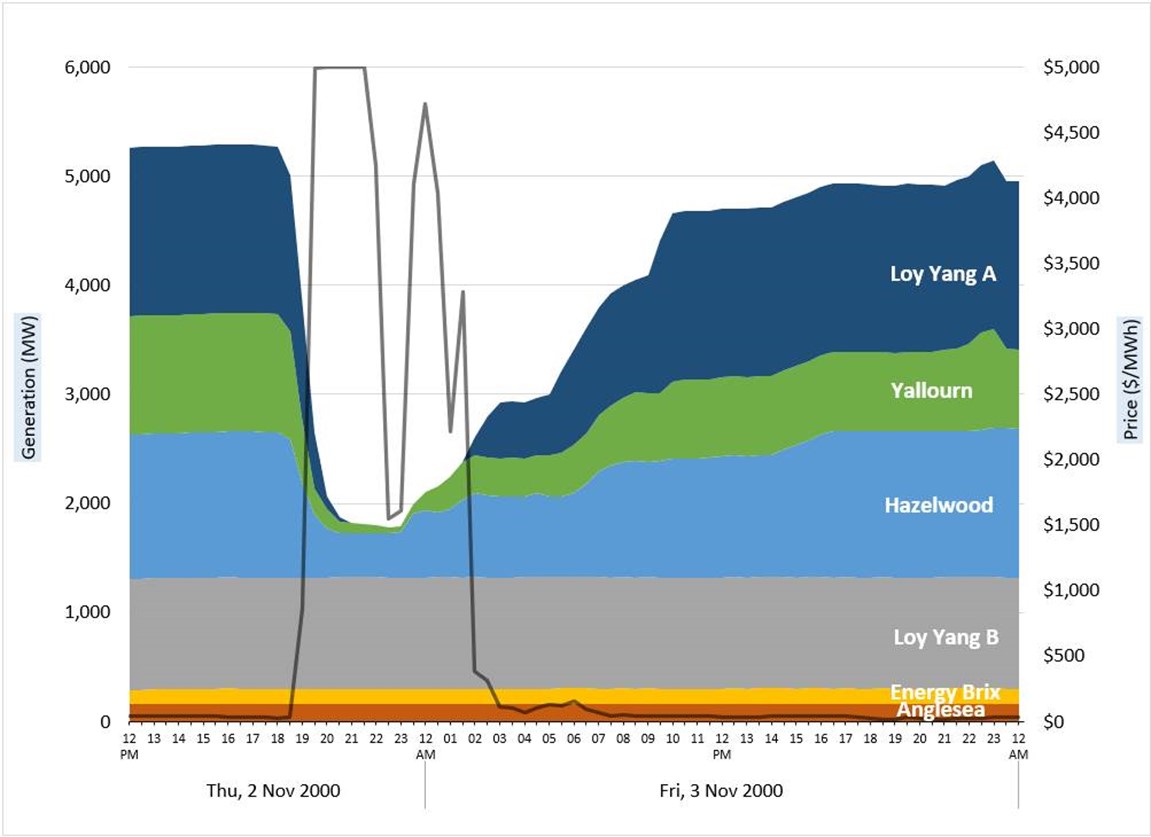

Figure 3: Victorian coal power station output during the wildcat strike and Victorian price

Source: AEC analysis of AEMO MMS data

Source: AEC analysis of AEMO MMS data

Management and government steps in

Within an hour of the action, Loy Yang A management had obtained a supreme court injunction against their own unit controllers and the CFMEU. This was however defied purportedly on the grounds that it was obtained outside court – at the Justice Barry Beach’s home[x].

Meanwhile urgent calls were made to the state government, and, within two hours it had re-activated its emergency powers to direct the workers to cease the action[xi]. By this time, all Loy Yang A units, two Yallourn units and five Hazelwood units had been shutdown. As can be seen in figure 3, it takes many hours to restart brown coal units. The last unit – at Hazelwood -was offline for nearly 24 hours. Meanwhile two other Hazelwood units were being operated by members of another union and were unaffected.

Lawyers, wildcats and money

CFMEU’s head office counsel against the action was wise: the workers’ unprotected actions had seriously exposed themselves to litigation. Loy Yang A, only a bystander to the Yallourn dispute, was unable to earn revenue to cover the payout on their hedge contracts during the high prices, incurring losses of around $20 million.

Then followed some stressful months for all. Seven Loy Yang controllers were stood down from their roles, and their employers commenced Federal Court proceedings against them personally, as well as the CFMEU.

The proceedings were ultimately settled. CFMEU agreed to Enterprise Bargaining concessions, including an agreement to never take such similar actions.

Conclusion

The industrial climate in the power industry has undoubtedly improved for the better during the 21st century. Whilst many critical roles remain unionised, changes in the ownership, technology, and broader industrial relations law, mean that what was once the industry’s greatest risk to supply has all but disappeared. For example, it seems quite inconceivable that operators of wind and solar farms would ever shut them down in a dispute.

For all those used to previously stage-managed industrial action, the wildcat strike was quite shocking in its reckless foolishness. It put the power system at great risk, and what were the workers thinking they could achieve by harming Yallourn’s competitors?

Whilst there are no winners from such an event, in hindsight unions were the biggest losers, as the legal limits to their power became all too evident to themselves, and to their employers.

The Australian Energy Council gratefully acknowledges the assistance of former spot traders; Darryl White, now of AEMO, and Jonathon Dyson, now of Greenview Strategic Consulting, in researching this article. Darryl and Jonathon had very long working nights on 2 November 2000.

[i] https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/from-the-archives-1989-bitter-day-for-all-but-heat-s-on-greiner-20190716-p527tt.html and see page 35 of https://research.iscrr.com.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/297180/to-strike-a-balance-a-history-of-Victoria-workers-compensation-scheme-1985-2010.pdf

[ii] See https://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/national/queensland/archive-documents-reveal-queenslands-1985-seqeb-dispute-20151231-glxgos.html

[iii] See page 240 of https://www.accc.gov.au/system/files/public-registers/documents/D04%2B30895.pdf

[iv] See page 3 of https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard/pdf/council/Autumn%202000/Council%20Parlynet%20Extract%2029%20February%202000%20from%20Book%201.pdf

[v] https://www.abc.net.au/am/stories/s98895.htm

[vi] https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2000/02/pow-f10.html

[vii] The Age, “Sparks Fly in High Voltage Feud” 4 Nov 2000

[viii] https://www.afr.com/politics/victoria-hit-by-power-strike-20001103-k9u34

[ix] Shedding light on the blackouts, The Age, 4 Nov 2000

[x] The Age, “Power Crisis triggers blackouts, restrictions” 3 Nov 2000

[xi] https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2000/12/vict-d22.html

Related Analysis

Judicial review in environmental law – in the public interest or a public nuisance?

As the Federal Government pursues its productivity agenda, environmental approval processes are under scrutiny. While faster approvals could help, they will remain subject to judicial review. Traditionally, judicial review battles focused on fossil fuel projects, but in recent years it has been used to challenge and delay clean energy developments. This plot twist is complicating efforts to meet 2030 emissions targets and does not look like going away any time soon. Here, we examine the politics of judicial review, its impact on the energy transition, and options for reform.

Climate and energy: What do the next three years hold?

With Labor being returned to Government for a second term, this time with an increased majority, the next three years will represent a litmus test for how Australia is tracking to meet its signature 2030 targets of 43 per cent emissions reduction and 82 per cent renewable generation, and not to mention, the looming 2035 target. With significant obstacles laying ahead, the Government will need to hit the ground running. We take a look at some of the key projections and checkpoints throughout the next term.

Certificate schemes – good for governments, but what about customers?

Retailer certificate schemes have been growing in popularity in recent years as a policy mechanism to help deliver the energy transition. The report puts forward some recommendations on how to improve the efficiency of these schemes. It also includes a deeper dive into the Victorian Energy Upgrades program and South Australian Retailer Energy Productivity Scheme.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.