The return of Trump: What does it mean for Australia’s 2035 target?

Donald Trump’s decisive election win has given him a mandate to enact sweeping policy changes, including in the energy sector, potentially altering the US’s energy landscape. His proposals, which include halting offshore wind projects, withdrawing the US from the Paris Climate Agreement and dismantling the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), could have a knock-on effect across the globe, as countries try to navigate a path towards net zero.

So, what are his policies, and what do they mean for Australia’s own emission reduction targets?

Offshore Wind Ban on "Day 1"

Trump has promised to end the offshore wind industry in the United States on his first day back in office, planning to sign an executive order to block all offshore wind projects. In a May 2024 speech, Trump criticised offshore wind as "the most expensive energy there is" and claimed it harms the environment by disrupting marine ecosystems and killing birds and whales. He has argued offshore wind “destroys everything” and vowed to ensure “that ends on Day 1” of his presidency.[i]

This promise could have far-reaching impacts on the current US offshore wind sector, which has about 65 gigawatts of capacity under development. Some turbines, off the coast of Rhode Island and Virginia, are already operating, but a sudden halt to offshore wind development would disrupt projects still under-development and likely deter further investments in this sector. Clean energy advocates see offshore wind as critical to meeting U.S. climate goals, while Trump and his supporters argue it imposes high costs and environmental risks. [ii]

Opposition to the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)

The Inflation Reduction Act, passed in 2022, has allocated hundreds of billions of dollars to green energy projects, electric vehicle (EV) incentives, and carbon reduction initiatives. Trump has been vocal about his desire to dismantle or significantly roll back the IRA, which he criticises as an unnecessary government subsidy for renewable industries. House Speaker Mike Johnson and other Republican leaders have also indicated their intent to repeal or reduce the IRA if the Republicans gain control of Congress in 2024. However, repealing the IRA could face resistance even within the GOP; approximately 85 per cent of IRA funds have benefited Republican-majority districts, leading some Republican lawmakers to defend it based on its positive economic impacts on their communities. In August, 18 Republican representatives wrote to Speaker Johnson urging him to not revoke all of the IRA if the GOP wins control of the House and Senate, a feat which was achieved, as a full repeal “would create a worst-case scenario where we would have spent billions of taxpayer dollars and received next to nothing in return.”[iii]

By repealing or curtailing the IRA, Trump would cut substantial support for clean energy projects that have drawn investments across the country. Some analysts argue curbing the IRA could slow down the clean energy transition but would not halt it entirely, as the renewables sector has gained momentum independent of government incentives. Nevertheless, any rollback would significantly alter the direction and pace of the US energy market’s shift toward renewables.

“Drill, Baby, Drill”: Increasing Domestic Oil and Gas Production

A key element of Trump’s energy policy is to “drill, baby, drill”, a commitment to increasing oil and gas production. Trump’s plans include expanding drilling on federal lands, particularly in areas like Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) and the Gulf of Mexico. Trump has also proposed fast-tracking permits for fossil fuel infrastructure, including pipelines and refineries, to further bolster U.S. oil and gas production

This aggressive push for fossil fuel expansion echoes Trump’s stance during his first term and builds on the US's already significant standing as the world's largest oil and gas producer, with its oil production having increased to record highs each year for the past six years.[iv] Trump argues increasing domestic production will reduce energy prices and strengthen US energy security. He has vowed to slash energy prices by 50 per cent.[v]

Withdrawing from the Paris Climate Agreement

In line with his 2017 decision to withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement, Trump has reaffirmed his intent to exit the accord once again. He previously stated the agreement is an unfair economic burden to the US, arguing it imposes strict emission requirements on American industries while allowing countries like China and India to continue producing high levels of emissions. Trump’s opposition to the Paris Agreement reflects his stance against binding international climate commitments, which he believes compromise US economic growth, while climate activists argue the US staying in the Paris Agreement is vital for it to maintain its influence in global climate negotiations and achieving collective goals to mitigate the effects of climate change.

Does any of this matter to Australia?

Last week, at the Senate Estimates, the Climate Change Authority said that its advice to the Federal Government on Australia’s 2035 emissions reduction target, which was initially due in October, had been delayed because they need to “consider things in the geopolitical environment’ and the outcome of the US election would have “a bearing on Australia’s place in this [2035] discussion”.

It seems the United States is unlikely to have a 2035 emissions reduction target, given President Trump’s verbal commitment to withdrawing from the Paris Agreement. Given there is a 12-month lag before this can officially happen, and President Trump will not be in office until January 2025, the earliest the US can withdraw is before COP 31.

This brings in another complication facing the Albanese Government – Australia has been lobbying to host COP 31 in partnership with the Pacific and seems likely to be successful. If this does play out as expected, then there will be pressure from all sides – domestic, regional, and international – for Australia to lead by example and have an ambitious 2035 target and climate policy agenda.

If that was not enough, the deadline for submitting updated targets (called NDCs – Nationally Determined Contribution) under the Paris Agreement is 10 February 2025. This means the 2035 target is primed for political controversy as the next federal election is, at the latest, in May 2025. The Opposition has already started positioning that the Federal Government’s interim targets will be an election issue.

The general interpretation to date has been Trump’s re-election has just added to the headache facing the Albanese Government. But it may also prove to be a lifeline. That is because all countries with climate ambition are monitoring what it means for the Paris Agreement and pathways to net-zero. This could result in many countries holding their announcements until after February, allowing Australia to follow suit. Energy Minister Bowen has already indicated as such:

"Countries around the world are indicating different timelines to me about when they might put theirs out … I expect some countries will put their targets out later next year, we'll see what countries do."

The timing of the announcement will obviously influence the level of ambition, as scrutiny about costs and achievability will have less political sting if it is a post-election announcement. This might allow a re-elected Albanese Government to make an announcement in the 65-75 percent range, which is hat the CCA flagged in its initial consultation.

As for the impact of Trump on Australia and the world’s 2035 ambition, crystal balling appears an exercise in futility. Last time, the United States’ withdrawal from the Paris Agreement was a motivating factor for countries to set higher ambition – higher ambition that they are currently not on track to meet.

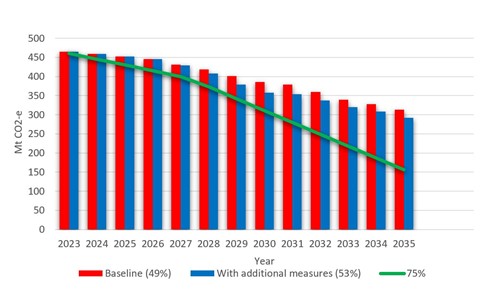

One smaller point of curiosity to come out of the Senate Estimates last week relates to how Australia forecasts its emissions pathways up until 2030 and 2035. Every year, DCCEEW publishes a document called Australia’s Emissions Projections. The most recent 2023 version shows Australia is projected to achieve 37 percent emissions reduction by 2030 (and 49 per cent by 2035) on 2005 levels, and then under a more ambitious scenario (relying on an assumption of 82 percent renewables by 2030), Australia will be 42 per cent by 2030 (and 53 per cent by 2035) on 2005 levels.

At the Senate Estimates, DCCEEW explained that the ambitious scenario’s assumptions would now be used in the baseline scenario in the 2024 Emissions Projections (yet to be published). That is because the Capacity Investment Scheme is now mature enough to allow an assumption the 82 per cent renewables target can be met.

This will likely allow the Federal Government to show its interim target is on track and achievable in the lead-up to the next election, as well as create space for a more ambitious emissions reduction trajectory out to 2035.

Figure 1: Australia’s Emissions Projections by scenario Mt CO2-e, 2023 to 2035

Note: the 75 per cent trajectory is based on pathway assumptions made in CSIRO Modelling Sector Pathways report, p65.

Some experts believe that a Trump administration pull back in funding for the IRA could see investment capital redirected back to Australia, potentially accelerating the country's energy transition. Nick Forster, Head of Power, Utilities, and Infrastructure Investment Banking at Citi Australia, spoke at the recent Australian Financial Review Infrastructure Summit, suggesting that Australia might capitalize on the U.S. "turning away" from renewable energy and climate priorities. He noted, “There’s an opportunity for Australia to potentially take advantage... and so whether that’s technology… or capital, to be able to try and attract that to Australia. I guess it’s a great opportunity.”[vi] This sentiment was echoed by other investment experts at the summit, who view the potential shift in US energy policy as a chance for Australia to strengthen its position in clean energy markets.

Trump’s proposal to ban offshore wind projects could also present a unique opportunity for Australia. With the U.S. potentially moving away from offshore wind, Australia might attract both investment and a skilled workforce for its growing offshore wind sector, which has faced challenges in recruiting talent. While these changes present promising possibilities, it remains to be seen how the geopolitical shifts and US policy adjustments will impact Australia’s energy landscape in the long term.

[i] https://apnews.com/article/trump-offshore-wind-energy-4e5b18ecd4799cc4cfd8cd7dc7b326ee

[ii] https://www.politifact.com/article/2024/sep/30/donald-trumps-2024-campaign-promises-heres-his-vis/

[iii] https://www.reuters.com/world/us/white-house-climate-adviser-touts-key-laws-benefits-red-states-2024-08-13/

[iv] https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=61545#:~:text=The%20United%20States%20produced%20more,six%20years%20in%20a%20row.

[v] https://www.npr.org/2024/09/22/nx-s1-5118358/fact-checking-former-president-trumps-promise-to-cut-u-s-energy-costs

[vi] Trump win could be good news for Australian energy transition

Related Analysis

2025 Election: A tale of two campaigns

The election has been called and the campaigning has started in earnest. With both major parties proposing a markedly different path to deliver the energy transition and to reach net zero, we take a look at what sits beneath the big headlines and analyse how the current Labor Government is tracking towards its targets, and how a potential future Coalition Government might deliver on their commitments.

Is time running out for new generation in WA?

As Western Australia edges towards its next State Election in March, the energy sector continues to be a hot button topic. Already this year, the South West Interconnected System (SWIS) has been forced to navigate record peak demand and highest demand days, a massive test for operators and market participants who successfully dealt with the challenge. Despite this resilience, the timely delivery of new generation will be critical to address the forecast capacity shortfall by the end of the decade and ensure a reliable and affordable system for industry and consumers. Removing the bottlenecks preventing new generation from connecting to the grid in a timely manner will be crucial. Here we take a look at the challenges of delivering new projects in WA and cast a spotlight on some of the issues that still need to be addressed.

Australia’s net zero plan is looking a lot like an electricity-only plan

The past three years have seen a stronger commitment to encouraging economy-wide decarbonisation, as seen through reforms to the Safeguard Mechanism and new policies like the New Vehicle Efficiency Standard and Future Made in Australia. But the release of two emissions reduction progress reports paints a sobering reality – no sector other than electricity is doing anything to help Australia meet its 2030 target. Is this leading to the proverbial “all eggs in one basket”? Or is electricity decarbonisation really the only viable pathway to 43 per cent by 2030? We take a closer look.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.