Solar flares: Fashioning the future?

“Upcoming solar flares could wreak havoc on Earth”[i] Sensationalist headline, or an element of truth?

What are solar flares and what are their effects?

Solar flares occur when magnetic energy that has built up in the solar atmosphere is suddenly released. Radiation is emitted across the entire electromagnetic spectrum, from radio waves at the long wavelength end, through optical emission to x-rays and gamma rays at the short wavelength end.[ii] It usually takes about a day or two for the emissions to reach Earth.

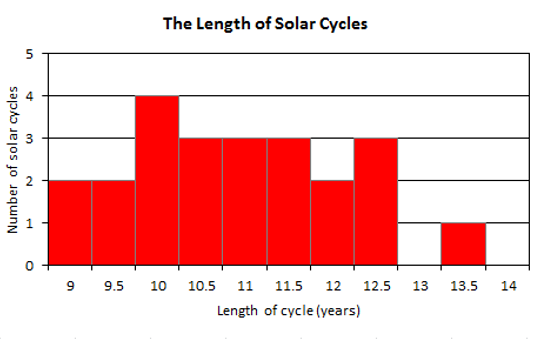

The frequency of solar flares is linked to the solar cycle, which varies between 9 years and 13½ years and averages 11 years.[iii]

Figure 1: The Length of Solar Cycles

Source: Bureau of Meteorology

In general the magnitude of solar flares is such that they are barely noticeable, and there are no effects on Earth except for auroral displays (e.g. Aurora Australis as shown in Figure 2, and Aurora Borealis). However extreme space weather events can affect satellites, GPS, communications systems and power systems.

Figure 2: Aurora Australis

Source: Department of the Environment and Energy, Australian Antarctic Division[iv]

Geomagnetic storms can cause geomagnetically-induced currents in transmission systems, which can flow through high-voltage power transformers, causing them to overheat and possibly fail. The currents can also cause system harmonics, unwanted power consumption and instability in the power system.

The largest solar flare event is the first one recorded, the ‘Carrington Event’, which occurred on 1 September 1859. NASA regards this event as a once-in-500-years event.[v]

However since that time, there have been a number of other significant solar flare events.

On 4 August 1972, a large solar flare knocked out long-distance telephone communication across Illinois. The event caused AT&T to redesign its power system for transatlantic cables.

In December 2005, X-rays from another solar storm disrupted satellite-to-ground communications and GPS navigation signals for about 10 minutes.

However the most significant effects from a solar flare occurred on 13 March 1989, when the ensuing geomagnetic storm, about a third the size of the Carrington Event, caused the collapse of the Hydro-Québec power grid in a matter of seconds as equipment protective relays tripped in a cascading sequence of events. Six million people were left without power for nine hours.[vi] If a similar storm-induced blackout had occurred in the north-eastern United States, the economic impact could have exceeded $10 billion, not counting the negative impact on emergency services and the reduction in public safety associated with the loss of electric power in large cities.[vii]

So what are the chances of this happening today?

Since 1989, power companies in North America, the United Kingdom, Northern Europe, and elsewhere have invested in evaluating the risk from geomagnetically induced currents (GICs) and in developing mitigation strategies. Protection from GIC events requires:[viii]

- detection systems;

- protective relays;

- capacitor blocking systems;

- strategies to isolate portions of the transmission system;

- additional on-demand generating capacity; and

- ultimately, load shedding.

These options are expensive and sometimes impractical.

Nevertheless to mitigate the risk, on 22 September 2016, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission approved Reliability Standard TPL-007-1 (“Transmission System Planned Performance for Geomagnetic Disturbance Events”), which establishes (from 1 July 2017 over a period of five years) requirements for transmission network service providers (TNSPs) to assess the vulnerability of their transmission systems to geomagnetic disturbance events, and collect relevant data and make it publicly available. TNSPs that do not meet certain performance requirements, based on the results of their vulnerability assessments, must develop a plan to achieve the performance requirements – within two years for non-hardware mitigation and within four years for hardware mitigation.

Possible Australian Effects

According to the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM)[ix], the worst case scenario of a high-impact geomagnetic storm may result in:

- partial loss of satellite infrastructure and disruption to satellite communications;

- significantly degraded and unreliable position, navigation and timing systems;

- intermittent disruptions to VHF & UHF telecommunications systems;

- loss of high frequency communications systems; and

- possible power supply instability and transformer damage.

The BOM notes that while widespread loss of power is unlikely, prolonged outages to major metropolitan areas could occur. It provides a geomagnetic warning (http://www.sws.bom.gov.au/Geophysical/2/1) and alert (http://www.sws.bom.gov.au/Geophysical/2/2) system.

Conclusion

While the likelihood of significant geomagnetic disturbances is low, the consequence can be significant. It is reassuring that transmission systems are considering this in their risk assessments.

[i] http://nypost.com/2017/04/21/earth-may-experience-blackouts-from-massive-solar-flares/

[ii] https://hesperia.gsfc.nasa.gov/sftheory/flare.htm

[iii] http://www.sws.bom.gov.au/Educational/2/3/7

[iv] http://www.antarctica.gov.au/__data/assets/image/0017/51371/varieties/square-sml.jpg

[v] https://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2008/06may_carringtonflare/

[vi] http://www.hydroquebec.com/learning/notions-de-base/tempete-mars-1989.html

[vii] https://geomag.usgs.gov/research/GIC.php

[viii] https://selinc.com/solutions/sfci/power-system-risk-mitigation/GIC-GMD/

[ix] http://www.sws.bom.gov.au/Category/Products%20and%20Services/Client%20Support/TISN/TISN_space-weather-information-sheet.pdf

Related Analysis

2025 Election: A tale of two campaigns

The election has been called and the campaigning has started in earnest. With both major parties proposing a markedly different path to deliver the energy transition and to reach net zero, we take a look at what sits beneath the big headlines and analyse how the current Labor Government is tracking towards its targets, and how a potential future Coalition Government might deliver on their commitments.

Transmission Access Reform: Has the time passed?

Last week submissions to the AEMC’s Transmission Access Reform consultation paper closed. It is the latest in a long running consideration of how best to ensure both efficient dispatch and investment in new generation to ensure new kit is sited in the best locations. But this continued pursuit of reform brings to the fore the question of whether other policy initiatives have already superseded the need for the proposed changes. We take a look at where the reform proposals have come from, as well as concerns about the suggested approach that have emerged.

EPBC Act: Does the Government have its finger on a climate trigger?

The Government’s Nature Positive Plan Reform has reignited the debate on whether Australia should add a climate trigger into our environmental protection laws. This was sparked after the Government announced stage three of the Nature Positive Plan would be focusing on “climate-related reforms, including the interaction between environment and climate laws.” So, what is a climate trigger and why is it such a contentious issue? We take a closer look.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.