Singapore: Some familiar issues in an unfamiliar context

In late July, Ben Skinner, General Manager Policy & Research, addressed a biennial conference[i] run by the Singapore market operator, the Energy Market Company (EMC). Along with other international speakers, Ben participated in committees discussing long-term market reform proposals for the National Electricity Market of Singapore (NEMS). Here he shares his reflections on a market and reform process that has some similarities, but also great differences, to our own…

Singapore and Australia: International parallels

Those experienced in the Australian National Electricity Market (NEM) would see many parallels in the design of the National Electricity Market of Singapore (NEMS). It is an energy-only market with a high price cap. Like the NEM, it has single-pass pricing (no day-ahead market), with self-commitment assisted by non-binding pre-dispatch forecasts.

It uses 30-minute ex-ante security-constrained dispatch and pricing periods and three kinds of co-optimised ancillary services to balance supply and demand within the half-hour. Bids can change right up to dispatch, but rebids made in the last 65 minutes are investigated.

Remarkably for such a small geographic area, it employs locational marginal (nodal) pricing on its generation fleet, whilst load is settled at a weighted average price. In practice there does not seem to be much price variation across the island.

Like the original Western Australian arrangements, the independent EMC is a market operator, but not the system operator. It and the network activities are overseen by the regulator, the Energy Market Authority (EMA). Like New Zealand, the market operator role is itself contestable: the Energy Market Company is on its second 10-year licence, and is owned by the Singapore (stock) Exchange.

Development of the industry and competition

The market officially began in 2003, and in 2008 the generation fleet was privatised into three main vertically-integrated energy companies. There is now strong competition with 15 registered generators, including cogenerators in Singapore’s large hydrocarbon processing industry.

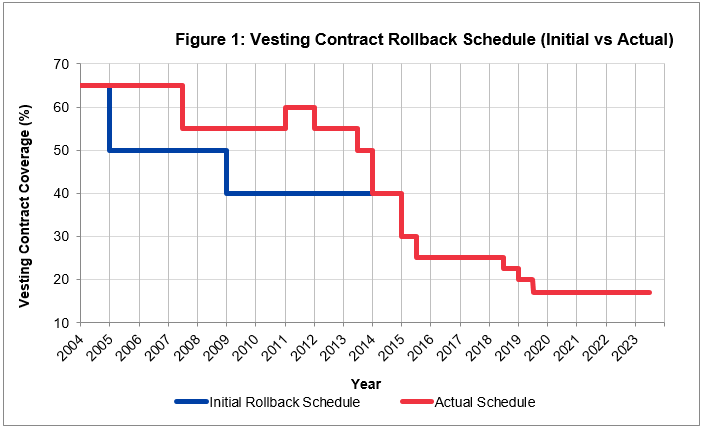

Like the NEM, retail competition opened progressively, and in the meantime vesting contracts covered the non-contestable load. Earlier this year, the entire market was opened to competition. Host retailing is provided by SP, performing a “retailer of last resort” function – supplying customers at a regulated price linked to the vesting contracts until they are won by competing retailers. SP itself does not compete for new customers. Thanks to current market conditions, customers who move off the legacy rate are receiving as much as 30 per cent discounts, so churn to market contracts has been high.

Source: EMC

Source: EMC

At first glance, this would seem to be a successfully competitive outcome delivering broadly what the market designers hoped for.

The physical situation

As a small city-state with no indigenous fossil fuel, NEMS could not be more different to the NEM and WEM. It has a modestly growing peak demand of just over 7,000MW, but Australians might struggle to consider it a “peak”, since the average load is just under 6,000MW: implying a load capacity factor of over 80 per cent.

There is an Alternate Current interconnector to Malaysia, however, this does not participate in the market and is only used in exceptional circumstances.

Practically, all generation is gas-fired. Installed capacity is around 13,500MW, symptomatic of a major over-supply.

Historically, gas came by pipe from Malaysia and Indonesia, however, in 2013[ii] a liquefied natural gas (LNG) import terminal was completed following a government commitment to diversify supply. Generators committed to long-term contracts from this new supply, which has led to an oversupply of fuel as well as capacity. As a consequence, spot market prices are low and conditions are financially challenging for the generators.

Renewable Energy

Around 200MW of solar is presently installed with an ambition to grow this to 1,000MW during the 2020s. Geography limits the ability to grow on-island renewable energy much beyond this, and post-Fukushima there is no enthusiasm for nuclear.

For a wealthy country, Singapore’s Paris Agreement commitment does not seem ambitious, with a commitment to reduce emissions intensity (ie per $ GDP) by 36 per cent from 2005 to 2030 and to stabilise absolute emissions by 2030. This does seem to dampen prospects for transformational projects as the Sun Cable [iii].

Capacity Market Proposal

Fitting 1,000MW of solar into an over-supplied gas-fired grid with a very flat customer demand sounds like a problem Australian market operators would love to have. Indeed, the swings in supply/demand would probably still be smaller than those the NEM and WEM began with, let alone are experiencing now.

Nevertheless, it is very much exercising the minds of the EMA and EMC who have committed to introduce a forward capacity market by 2022 [iv]. This is largely modelled off the Pennsylvania-New Jersey-Maryland (PJM) market design, with three-year rolling auctions for capacity to meet the forecast peak plus a reserve margin. Meanwhile the energy-only market will continue to operate alongside.

The rationale for the change appears to be:

- A firm desire to maintain at least a 30 per cent reserve margin of non-intermittent plant above peak demand. Whilst this is seen as politically necessary, it is well above what energy-only markets such tend to deliver over the long-term. Indeed 30 per cent seems inefficiently large and well above the WEM’s capacity market settings.

- Concern about the long-term ramifications of the current low prices. The oversupply may drive the exit of many plants, whilst discouraging new-entry, which may move the market from over to under-supply during the 2020’s.

Similar concerns were raised by parts of the NEM’s industry during its over-supplied period of 2014-15, with capacity markets being proposed as a way of smoothing the economic cycles. It may be observed that the Singaporean concerns about the next decade have parallels to the NEM’s real experience in the current decade.

Demand-side Mechanism

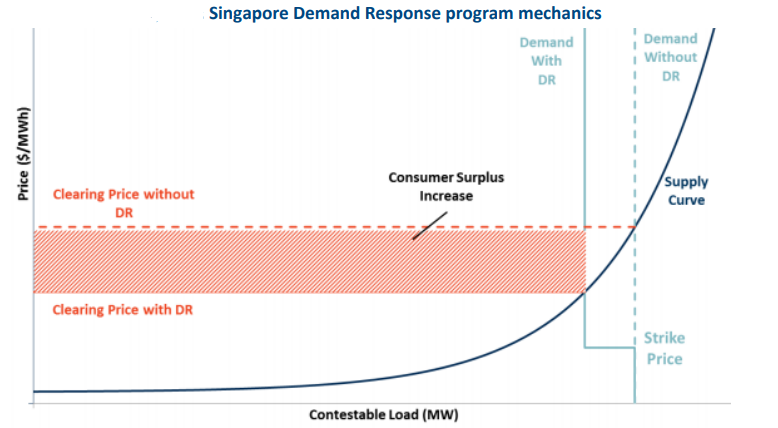

In 2016 the NEMS introduced a unique reward for demand-side response, which involves sharing the consumer surplus created by reducing the market price. This was studied in the current AEMC rule change determination of a demand-response mechanism for the NEM. In the diagram below, one-third of the value of the orange box is levied on customers not responding and paid to those responding.

Figure 2:

Source: Brattle Group for AEMC

Source: Brattle Group for AEMC

As identified by the AEMC’s consultant, Brattle, take-up of this mechanism in the NEMS has been very low. This is not necessarily a bad outcome, as there would be expected to be little value in demand response in such a stable market. It was interesting to discover however that it seemed an unpopular mechanism. Many parties doubted the economic rationale of sharing such a surplus, especially the customers being levied, whilst demand-response aggregators strongly disliked the operational constraints they needed to comply with to benefit from it.

This is not the mechanism being proposed for the NEM [v], but there is perhaps a lesson here for any such scheme that attempts to provide additional incentives to a desirable activity through an artificial mechanism outside of normal market processes. Rather than sating the activity’s supporters, it inevitably leads to evermore criticism of the mechanism chosen to sate them.

Conclusion

It is fascinating to observe a market design that has many similarities to those in Australia, and has experienced similar successes and challenges, yet is operating on a power system that could not be more alien.

And whilst the governance and consultation processes for market reform look very similar to Australia’s, they occur in what is a very different cultural environment. Parties seem to think long-term and are less publically adversarial. Once key decisions, such as the introduction of the capacity market, are made parties seem to resign themselves to the decision and the consultation process limits itself to details.

There are no industry associations such as the Australian Energy Council active in the NEMS. It is not clear whether this absence is a consequence of, or a cause of, the less combative regulatory environment.

[i] EMC, Singapore Electricity Roundtable 2019

[ii] SLNG, Newsroom: https://www.slng.com.sg/website/newsroom.aspx?mmi=60

[iii] Suncable. The project overview says it will produce approximately a fifth of Singapore's electricity through solar power, sourced from the Australian desert near Tennant Creek and transmitted via a High Voltage Direct Current (HVDC) cable.

[iv] EMA, Consultation Paper - Developing a Forward Capacity Market to Enhance the Singapore Wholesale Electricity Market

[v] Wholesale Demand Response Mechanism: Poised to go ahead

Related Analysis

The ‘f’ word that’s critical to ensuring a successful global energy transition

You might not be aware but there’s a new ‘f’ word being floated in the energy industry. Ok, maybe it’s not that new, but it is becoming increasingly important as the world transitions to a low emissions energy system. That word is flexibility. The concept of flexibility came up time and time again at the recent International Electricity Summit held in in Sendai, Japan, which considered how the energy transition is being navigated globally. Read more

2025 Election: A tale of two campaigns

The election has been called and the campaigning has started in earnest. With both major parties proposing a markedly different path to deliver the energy transition and to reach net zero, we take a look at what sits beneath the big headlines and analyse how the current Labor Government is tracking towards its targets, and how a potential future Coalition Government might deliver on their commitments.

International Energy Summit: The State of the Global Energy Transition

Australian Energy Council CEO Louisa Kinnear and the Energy Networks Australia CEO and Chair, Dom van den Berg and John Cleland recently attended the International Electricity Summit. Held every 18 months, the Summit brings together leaders from across the globe to share updates on energy markets around the world and the opportunities and challenges being faced as the world collectively transitions to net zero. We take a look at what was discussed.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.