RECkoning with the RET?

The Renewable Energy Target (RET) has been in the news again in recent weeks, following the announcement by one retailer that it expected to pay the shortfall penalty to meet part of its liability[1]. This comes following a year in which Renewable Energy Certificate (REC) prices reached all-time highs. Despite this apparent signal of a scarcity of supply of RECs, the Clean Energy Council declared this the biggest year for renewables investment since the Snowy Hydro scheme[2]. We examine how it can be simultaneously both the best of times and the worst of times for renewables in Australia.

Rising prices

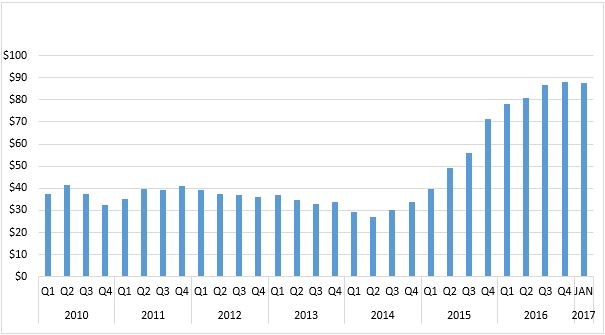

For much of the period following the enhancement of the RET in 2010, to 45,000 GWh pa by 2020 the spot price was somewhere between $30/$40 per MWh. Recently, it has more than doubled, with spot prices over $80/MWh. The price path is shown in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1 Quarterly Average prices for RECs 2010-2017

Source: Australian Energy Council analysis, 2017

It’s important to note that the spot price is only the marginal price. Most RECs are procured via long-term contracts. In some cases, the price may cover energy as well, so there is no explicit REC “price”. But as always the marginal price is a useful indicator of how tight the supply/demand balance is overall.

How does the shortfall work?

The RET legislation wisely contains a safety valve. Liable entities (retailers and some large users) can choose to pay a shortfall charge rather than surrender certificates. The charge is set at $65 per certificate not surrendered, but because it is not a tax-deductible expense (whereas the cost of acquiring certificates is), it is considered to have an effective value of around $93 (designed to act as a deterrent to deliberate failure to acquire certificates). Businesses may value the deterrent lower depending on their tax position, which could explain why they may elect to pay a shortfall even when certificates are available at a lower price.

Whilst it is a disappointing outcome for the penalty shortfall to be triggered, it is a useful element of the legislation. While the goal of the RET is to increase renewable energy in Australia, there is no sense that this goal is to be achieved at any cost. Accordingly, the penalty mechanism reflects the cap policymakers put on the cost of renewable energy that consumers are obliged to bear.

Secondly, the purpose of setting the liability on retailers, who operate in competitive markets, was to use the power of competition to minimise the cost of procuring the new renewables. This market dynamic is best served by having a cap. Otherwise, suppliers of renewable energy certificates know that the buyers have to buy a certain quantity at any price, which gives them additional negotiating power. Given that on top of the mandatory requirement, there are some parties that procure RECs for voluntary surrender, a cap does not mean that the supply of RECs be constrained – it just depends whether voluntary buyers are willing to pay more than $93 for a certificate. If they are not, then why would it be good value for mandatory buyers to bear that cost?

In this context it is disappointing that the Clean Energy Regulator has made comments suggesting that paying the shortfall is “a failure to comply with the spirit of the law[3]”. It appears entirely consistent and appropriate for a liable entity to minimise their costs in this way when faced with a high price for certificates. As in any market the price is dependent on both buyers and seller, so it would make as much sense to criticise renewables developers for failing to offer certificates at a reasonable enough price that a liable entity could minimise its cost. But in practice they are clearly not able to do so, perhaps reflecting the ongoing policy uncertainty. In particular, new assets can only earn RECs until 2030, which is well before their end of their expected lifespan.

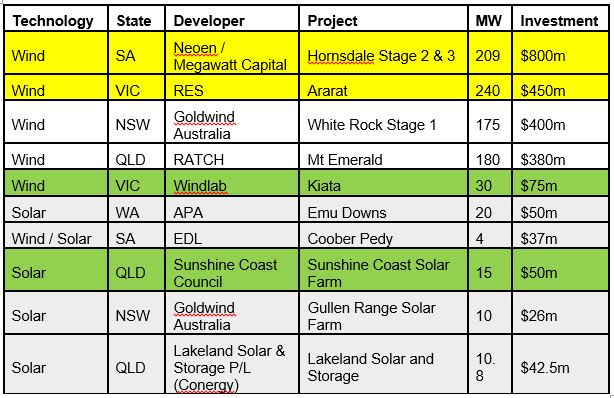

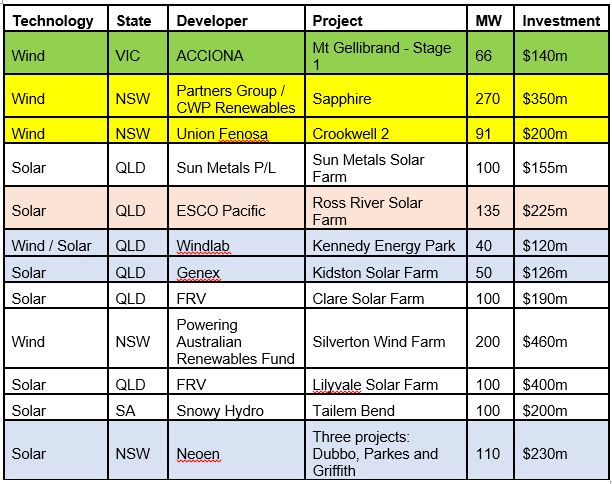

While the spot price, as the marginal REC price, reflects the risk premium many developers/owners require, assets are still getting built. The Clean Energy Council (CEC) has compiled a list of projects either currently under construction or planned to start during 2017 (i.e in total these projects represent more than a single year’s worth of investment). We have identified the projects that have benefited from government support over and above the RET.

Table 1 Projects under construction

Table 2 Projects with financial commitment – to start construction in 2017

Index

Source: Clean Energy council, Australian Energy council analysis, 2017

The major government sponsor is the ACT which has contracted at fixed prices for 482.5 MW of capacity. The ACT also voluntarily surrenders the RECs, so effectively has taken low cost capacity out of supply to the mandatory REC market.

Victoria has bought the RECs from two wind farms in the state (96 MW), but this is to cover its own indirect liability as a major consumer of electricity, so this appears to be simply about ensuring its REC costs are incurred on in-state projects, which could not be guaranteed if it simply left it to the retailer. The Sunshine Coast council has directly invested in solar to an amount equivalent to its own consumption.

ARENA has put almost $100 million into a range of projects - only a few of these are from its large scale solar round, so there are more to come.

CEFC has put $20 million of equity into the Ross River Solar farm and $267 million of debt across three other projects. Ostensibly, CEFC funding is on commercial terms, although it also claims not to simply be displacing private capital. The Kidston solar farm scored a triple whammy, obtaining a grant from ARENA, an offtake contract from the Queensland government and debt finance from CEFC.

Other than the government contracted projects, most of the projects above have supply contracts with retailers, including Origin, AGL, Energy Australia and Lumo. Two projects of note are those that don’t have supply contracts. Sun Metals’ project is for its own use, marking the largest direct investment in renewables by a commercial/industrial user in Australia. Goldwind’s White Rock windfarm apparently reached financial close without an offtake agreement, making it perhaps the only merchant plant on the list. This project would be an obvious potential supplier of RECs to retailers who need additional certificates to meet their liability (though it may have since contracted). Even where the shortfall penalty has been paid, the scheme is flexible enough to allow liable entities up to three years to backfill with RECs and get the penalty refunded.

The conclusion of all this construction and commercial activity is that, yes, renewables projects are getting built. After all retailers need RECs, and market intelligence suggest that the previous oversupply (stemming from the solar multiplier that applied to small scale solar PV before the scheme was split into two) has more or less been exhausted. But even so, it is taking a combination of federal and state support over and above the RET to drive enough projects to keep up with demand. Next year should see most of the other ARENA large-scale solar projects under construction, plus Victoria and Queensland have both indicated they will start underwriting new renewables in their respective states to meet their 50 per cent targets. Whether you see the renewables glass as half empty or half full, it looks like it will be a white knuckle ride towards 2020 when the target caps out.

[1] http://www.ermpower.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/ERM-Power-announces-LGC-fulfilment-plan-for-2016-240117.pdf

[2] https://www.cleanenergycouncil.org.au/news/2017/February/2017-renewable-energy-projects-snowy-hydro.html

[3] http://www.cleanenergyregulator.gov.au/RET/Pages/News%20and%20updates/NewsItem.aspx?ListId=19b4efbb-6f5d-4637-94c4-121c1f96fcfe&ItemId=338

Related Analysis

Nuclear Fusion Deals – Based on reality or a dream?

Last week, Italian energy company ENI announced a $1 billion (USD) purchase of electricity from U.S.-based Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS), described as the world’s leading commercial fusion energy company and backed by Bill Gates’ Breakthrough Energy Ventures. CFS plans to start building its Arc facility in 2027–28, targeting electricity supply to the grid in the early 2030s. Earlier this year, Google also signed a commercial agreement with CFS. These are considered the world’s first commercial fusion-power deals. While they offer optimism for fusion as a clean, abundant energy source, they also recall decades of “breakthrough” announcements that have yet to deliver practical, grid-ready power. The key question remains: how close is fusion to being not only proven, but scalable and commercially viable, and which projects worldwide are shaping its future?

Community Power Network Trial: Potential risks and market impact

Australia leads the world in rooftop solar, yet renters, apartment dwellers and low-income households remain excluded from many of the benefits. Ausgrid’s proposed Community Power Network trial seeks to address this gap by installing and operating shared solar and batteries, with returns redistributed to local customers. While the model could broaden access, it also challenges the long-standing separation between monopoly networks and contestable markets, raising questions about precedent, competitive neutrality, cross-subsidies, and the potential for market distortion. We take a look at the trial’s design, its domestic and international precedents, associated risks and considerations, and the broader implications for the energy market.

Competition a key to VPP development: ACCC report

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s most recent report on the electricity market provides good insights into the extent of emerging energy services such as virtual power plants (VPPs), electric vehicle tariffs and behavioural demand response programs. As highlighted by the focus in the ACCC’s report, retailers are actively engaging in innovation and new energy services, such as VPPs. Here we look at what the report found in relation to the emergence of VPPs, which are expected to play an important and growing role in the grid as more homes install solar with battery storage, the benefits that can accrue to customers, as well as potential areas for considerations to support this emerging new market.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.