Reactions to new nuclear report rekindles debate

The release of a New South Wales report last week, along with the Federal Government’s plans to release a technology roadmap have helped rekindle the debate about the suitability of nuclear generation for Australia’s power system.

The debate has been further fuelled via calls for the Federal Government to include nuclear power in its technology plan[i] which have come from the chair of the Federal House of Representative’s Standing Committee on the Environment and Energy, Liberal National MP Ted O’Brien.

Late last year that Standing Committee released its report into the prerequisites for nuclear energy in Australia[ii], which the Federal Government is yet to formally respond to.

The more recent report from the NSW Legislative Council’s Standing Committee on State Development, released on 4 March, follows a Bill put forward by One Nation’s Mark Latham that seeks to repeal NSW’s ban on uranium mining and nuclear facilities. That Bill was referred to the Upper House committee for further consideration.

There has also been a flurry of media following NSW National Leader and Deputy Premier ohn Barilaro's declaration that the Nationals will support the bill[iii], and the airing of opposing views in government ranks.

And the major hurdles remain: how to gain community backing to change the existing laws, as well the cost of nuclear technology and what role it could play. In a dissenting, Labor members said that “on the basis of current technologies and costs, we remain unconvinced of the benefits nuclear power may bring”[iv]. And Federally Labor opposes nuclear power and last week called on the Prime Minister “to come clean and confirm with Australian communities if expensive nuclear power is part of the government’s ‘technology roadmap’”.[v]

So what did the most recent reviews recommend and how would they overcome these barriers?

Federal review

The Federal Energy and Emission Reductions Minister, Angus Taylor, requested the Federal Parliament’s Standing Committee on the Environment and Energy to investigate nuclear as a power source for Australia. The rationale is the long-term need for low emission, affordable sources of baseload generation. The Minister has argued that it would be irresponsible not to consider technologies such as nuclear[vi].

The Standing Committee report’s recommendations included:

- that the Australian Government lift the moratorium on nuclear energy in relation to Generation III+ and Generation IV nuclear technology, including small modular reactors subject to a technology assessment by Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO), or other expert body, and a commitment to the “prior informed consent of local impact communities” and,

- that the Productivity Commission or similar body undertake an independent review of the economic viability of nuclear generation.

The NSW inquiry report findings included:

- that Generation III/III+ and Generation IV are a significant advancement on older generation reactor designs that were in operation when the prohibition was placed on nuclear facilities; and,

- that overall nuclear power to be a compelling technology that may be useful in energy policy which seeks to address the energy trilemma.

Its recommendations were along similar lines to the Federal inquiry, including that:

- the NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment liaise with ANSTO to monitor the regulatory approval and commercialisation of Small Modular Reactors in the United States and elsewhere (as appropriate) and report findings to the NSW Government as they become available; and,

- the NSW Chief Scientist and Engineer report to the NSW Government on broader developments in nuclear energy on a regular basis;

- the NSW Government commissions independent and detailed analysis and modelling to properly evaluate the viability of nuclear energy from an economic perspective, taking into account:

- all relevant inputs and variables as well as the specificities of the New South Wales electricity system;

- the costs for any new connection, transmission or other system/network infrastructure that would be required over and above the State's existing network infrastructure; and,

- the projected impact on NSW climate emissions and any opportunities or costs that entails or avoids.

These latest inquiries followed the earlier South Australian Royal Commission into the nuclear fuel cycle that found in 2016 that nuclear energy would not be commercially viable under existing market conditions, but that it may be needed as part of Australia’s energy system as we shift to lower emissions. It noted that it would “be wise to plan now to ensure that nuclear power would be available should it be required”.

The hurdles

The hurdles remain large, if not insurmountable. Community sentiment towards nuclear power may have improved overall, according to an Essential poll in June last year, but when asked “would you be comfortable living close to a nuclear power plant” 60 per cent of respondents still say no, with only 28 per cent saying they had no issue[vii]. Prior informed consent on that basis will remain a significant barrier to changing the laws.

The costs of nuclear technology also remains hotly contested, as evidenced by the most recent inquiries. There has been a recent history of cost overruns. The commercial viability of traditional, large-scale nuclear plants has been questioned, based on overseas developments, such as the Hinkley Point C nuclear generator in the UK[viii] along with cost blowouts in the US[ix].

More traditional, baseload nuclear plants at large scale lack flexibility, and advocates now point to the potential for small modular reactors (SMR) to fit with Australia’s grid and energy needs.

Both recent parliamentary inquiries point to the potential cost benefits from SMRs.

ANSTO advised the Federal Standing Committee on Environment and Energy that SMRs could reduce the cost of nuclear generation by:

- using passive safety features

- shifting the majority of construction to off-site and using modular manufacturing techniques; and,

- reducing plant build times.

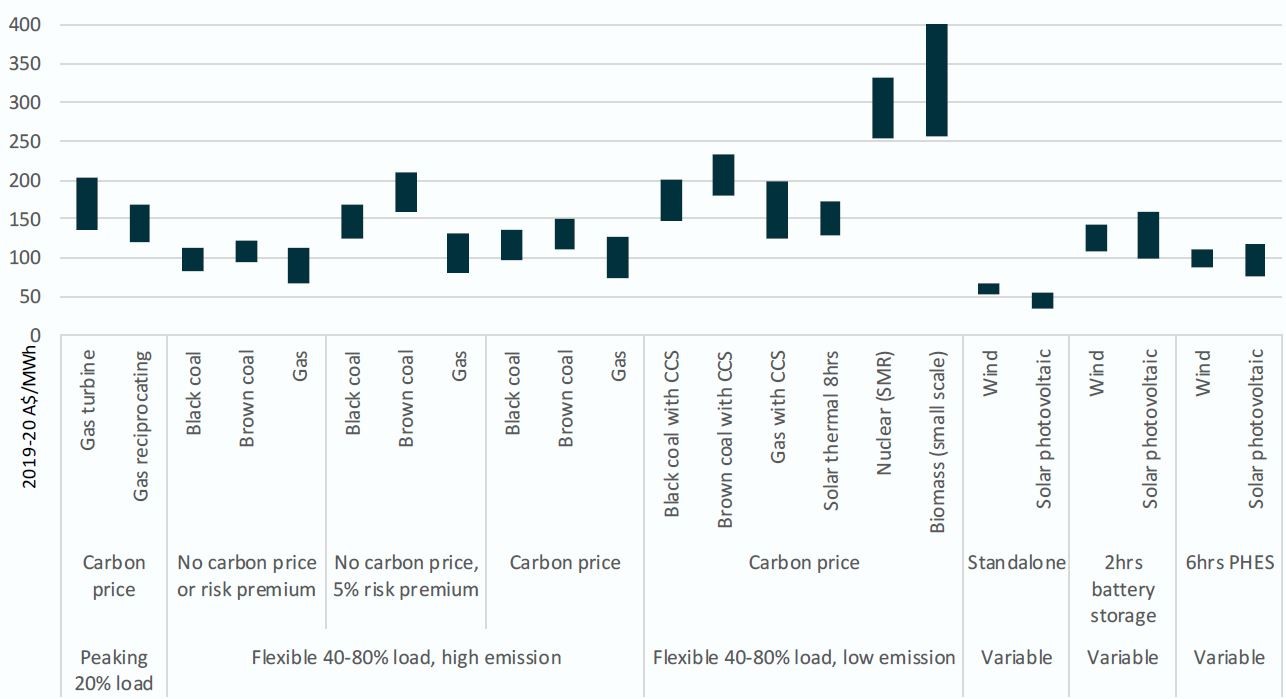

A December 2019 GenCost report by the CSIRO and the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) finds that construction costs for nuclear reactors are 2‒8 times higher than costs for wind or solar. Costs per unit of energy produced are 2‒3 times greater for nuclear compared to wind or solar including either two hours of battery storage or six hours of pumped hydro energy storage.

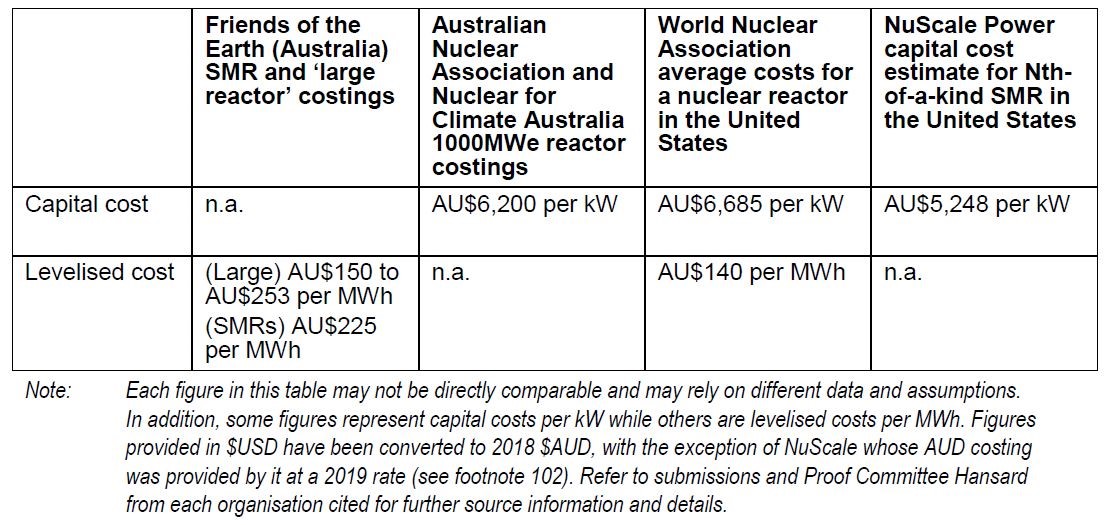

The earlier costings in the GenCost 2018 report [x] were dismissed in the Federal Standing Committee’s report on the basis that it did not provide a suitable assessment because it could not be verified. In the preliminary GenCosts 2019-20 the assumed current capital cost for nuclear SMR remains the same as GenCost 2018, which was sourced from GHD. The GenCost report notes that while SMR costs are “very uncertain due to the lack of public cost data on completed international projects, the GHD (2018) estimate remains reasonable for a technology at a low level of commercial deployment".

It did find that the cost projections were too narrow because they did not allow for cost improvements over time and the CSIRO’s latest projection model was modified to include SMR as a separate nuclear technology category, with a higher learning rate rather than in the broad nuclear category. As a result it projects a substantial cost reduction to around $7000/kW in the early 2030s[xi].

The NSW Parliamentary committee's report accepted that it is difficult to estimate the cost of nuclear energy in a country like Australia because of the lack of a history of nuclear energy and received a wide variation in levelised cost of electricity (LCOE) costs, with figures ranging from $325/MWh to $60/MWh. The Preliminary GenCost 2019-20 report estimates the LCOE for various technologies in 2020 as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1: Calculated LCOE by technology and category for 2020

Source: GenCost 2019-20: Preliminary results for stakeholder review, December 2019

Source: GenCost 2019-20: Preliminary results for stakeholder review, December 2019

Table 1 shows some of the cost estimates submitted to the Federal Parliamentary inquiry.

Table 1: Selected nuclear reactor cost estimates provided to Standing Committee on the Environment and Energy (House of Representatives)

Source: Report of the inquiry into the prerequisites for nuclear energy in Austrlaia, December 2019

Source: Report of the inquiry into the prerequisites for nuclear energy in Austrlaia, December 2019

While there will continue to be calls for nuclear generation to be part of the National Electricity Market it remains “expensive, unpopular and illegal”[xii]. Nuclear is likely to continue to struggle to compete against technologies like solar and storage, so the current debate may in fact be “one for “intellectuals and advocates”[xiii].

[i] Key Coalition MP urges nuclear rethink, Australian Financial Review, 25 February 2020

[ii] Not without your approval: a way forward for nuclear technology in Australia – Report of the inquiry into the prerequisites for nuclear energy in Australia, House of Representatives Standing Committee on the Environment and Energy, December 2019

[iii] https://www.smh.com.au/politics/nsw/barilaro-s-nuclear-push-bitterly-dividing-coalition-20200308-p547zm.html

[iv] Uranium Mining and Nuclear Facilities (Prohibitions) Repeal Bill 2019, NSW Legislative Council, Standing Committee on State Development, March 2020

[v] Government calls for nuclear power grow, 5 March 2020, ALP Media Release

[vi] “Is there really a nuclear option for Australia?”, EnergyInsider, 8 August 2019

[vii] https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/jun/18/australians-support-for-nuclear-plants-rising-but-most-dont-want-to-live-near-one

[viii] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-09-25/edf-raises-cost-of-flagship-u-k-nuclear-project-warns-of-delay

[ix] https://thebulletin.org/2019/06/why-nuclear-power-plants-cost-so-much-and-what-can-be-done-about-it/

[x] GenCost is an annual assessment of electricity generation and storage costs

[xi] GenCost 2019-20: preliminary results for stakeholder review, December 2019

[xii] “Why nuclear power might be our Plan B”, Australian Financial Review, 15 August 2019

[xiii] “No investment appetite for nuclear: Switkowski”, Australian Financial Review, 6 August 2019

Related Analysis

Certificate schemes – good for governments, but what about customers?

Retailer certificate schemes have been growing in popularity in recent years as a policy mechanism to help deliver the energy transition. The report puts forward some recommendations on how to improve the efficiency of these schemes. It also includes a deeper dive into the Victorian Energy Upgrades program and South Australian Retailer Energy Productivity Scheme.

2025 Election: A tale of two campaigns

The election has been called and the campaigning has started in earnest. With both major parties proposing a markedly different path to deliver the energy transition and to reach net zero, we take a look at what sits beneath the big headlines and analyse how the current Labor Government is tracking towards its targets, and how a potential future Coalition Government might deliver on their commitments.

The return of Trump: What does it mean for Australia’s 2035 target?

Donald Trump’s decisive election win has given him a mandate to enact sweeping policy changes, including in the energy sector, potentially altering the US’s energy landscape. His proposals, which include halting offshore wind projects, withdrawing the US from the Paris Climate Agreement and dismantling the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), could have a knock-on effect across the globe, as countries try to navigate a path towards net zero. So, what are his policies, and what do they mean for Australia’s own emission reduction targets? We take a look.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.