Power plant shutdowns: How Do You Prepare For The Transition?

With the recent closure of coal-fired power plants there has been increased talk for the need of a transition plan for potentially impacted regions like Victoria’s Latrobe Valley[i].

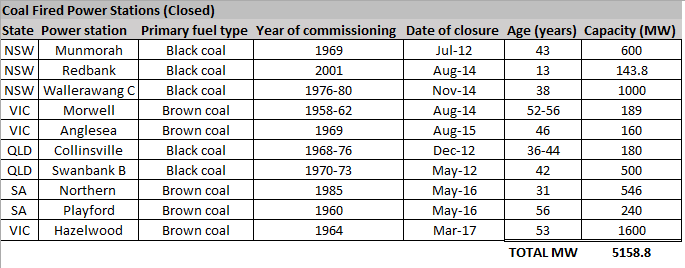

Since 2012, 10 coal fired generators have exited the National Electricity Market (NEM) taking more than 5000MW of capacity with them (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Coal-fired power station closures

Source: AEC Analysis, 2018

Based on the age of Australia’s fleet of coal fired generators, we can expect to see the retirement of another 15,000MW over the next 15-20 years. While more future coal-fired power station closures are planned, they are spread over time allowing for a planned transition process.

Figure 2: NEM coal generation fleet if plant retires as announced or at 50th year from full operation Source: AEMO, 2018

Source: AEMO, 2018

Despite that, the CFMEU’s Mining and Energy division has tried to raise it as an urgent issue by commissioning a University of NSW (UNSW) report, which calls for the establishment of an independent Energy Transition Authority to prepare local workers, families, and communities for the closure of Australia’s 23 coal-fired power stations by 2050[ii].

Ruhr or Appalachia?

The UNSW report The Ruhr or Appalachia? Deciding the futures of Australia’s coal power workers and communities, states that the transition of how we produce power will be a great change to the workers and communities who we have relied on to provide energy – and in the absence of sufficient policy-making, these workers will carry the heaviest costs such as early retirements, under and unemployment, and work that is lower paid or less skilled.

It recommends that a Federal Government authority should be established to work with all stakeholders well in advance of plant closures to manage the effect on workers and local communities. And has called for a comprehensive, long-term and staggered strategy to help workers transition.

The UNSW report looks at international examples and points to Appalachia, a region in in United States, characterised by short-term responses to closures of coal mines which resulted in intergenerational poverty. And compares this to Germany’s Ruhr region, which through a ‘just transition’ reshaped the regional economy with no forced job losses. It states that central to these outcomes is the presence of a national, coordinated response and proposes the establishment of an independent statutory authority to plan and manage the transition.

“Essential is a new regulatory structure as well as a change in policy culture. As each local case may be different, national policy making will need to adapt to local circumstances,” the report says.

It also recommends a package of policies to support a transition in affected regional communities, such as promoting geographical hubs or ‘clusters’ for new high-tech industries and services; and public sector investment in infrastructure projects to generate employment.

“A just transition process can revitalise regions dependent on coal-fired power stations and provide substantial opportunities to generate good jobs – if planning begins well ahead of closures,” UNSW Business School’s Professor Sheldon said.

“The best mechanism for this is a national framework that mandates proper planning and implementation. International evidence tells us that such a framework will require active participation from companies, workforce union representation, and government[iii].”

Last year, the Finkel Review panel recommended a policy package to transition to a low emissions future, and part of this was putting in place notice of closure requirements for large generators which, it states, would also give time for communities to adjust.

In response to more recent power plant closures, such as Hazelwood, the Australian Energy Market Commission made a draft rule in August this year, which would require scheduled and semi-scheduled generators to give the Australian Energy Market Operator at least three years notice of their intention to close – this was based on one of the recommendations of the Finkel Review (previously covered here).

Complementary to the notice of closure requirement, the Finkel Review also states that a 50 year lifetime limit on coal-fired generators could also give more forward certainty to workers and communities affected by closures: “Forward visibility of when coal-fired generation assets close would give communities and governments greater ability to plan for and manage potential impacts to regional economies,” the report says[iv].

Consideration of the need to manage the transition underway in the energy sector is not new. Back in 2008 The Garnaut Climate Change Review[v] stated that a flexible labour market, with sufficient employment opportunities and a strong social safety net could prevent the need for targeted government assistance.

In terms of long term impacts, Garnaut wrote that regional communities and industries were likely to be more vulnerable than urban centres due to their larger reliance on natural-resource industries along with low levels of infrastructure stock. (And as covered in a previous EnergyInsider, the skill needs of new generation technologies are different in terms of both the number and type of occupations required compared to more traditional coal-fired power stations. In the case of wind and solar generation, once construction is complete new renewable generation generally require much fewer ongoing staff.)

Garnaut states that the capacity of the labour market to adjust to change is influenced by the ‘ease of mobility’ - e.g. the ability to change a job in the same industry, and/or a change in occupation or location. Workers in declining industries who have a reduced range of re-employment or who must move to another location to find work, are likely to be the most disadvantaged.

Garnaut did note, however, that where transitional assistance is required, government must consider the most appropriate form of targeted assistance and he proposed a specific allocation of funding to facilitate structural adjustment in the industry - like retrofitting a facility with low-emissions technologies, and, if these new technologies were unlikely to be achievable, government would then need to re-train workers for new employment and provide grants to communities to support improvements in infrastructure that would help to attract alternative industries.

Rebuilding coal communities

As a response to the likely impact of the transition on the Latrobe Valley, the Victorian Government and SEA Electric recently announced that an electric vehicle (EV) factory would be developed in Morwell, with the aim of bringing up to 500 manufacturing jobs to the Latrobe Valley[vi].

The new EV plant would be capable of producing 2400 four-tonne electric vans and commuter buses. The five-year deal with SEA Electric has been signed and the Victorian Government’s support is expected to come from a $266 million Latrobe Valley support package that it set up to assist Hazelwood power station and Carter Holt forestry workers, when the operations closed last year[vii].

The closure of Hazelwood was long speculated due to slowing growth in electricity demand, Australia’s emissions reductions goals, the renewable energy target expanding investment in new generation, and the age of the plant.

It was announced in November 2016 that the Federal Government would deliver $43 million to support Hazelwood workers and the Latrobe Valley following the closure of the facility at the end of March 2017. The then Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull created a Ministerial Committee to work with all levels of government and the community to help the Latrobe Valley community, particularly affected workers and their families, manage the transition. And the Victorian Government established the Latrobe Valley Community Facility Fund to support regional projects. It was recently reported that the State Government’s Latrobe Valley Authority had allocated the full $266 support package on schemes such as a Worker Transition Service that has helped 1,141 workers and their families retrain to find new jobs, development of an Economic Growth Zone, and improving sporting infrastructure in the region[viii].

Across the border, Port Augusta in South Australia has also felt the impact of the Northern power plant closure in May 2016, which resulted in the loss of 185 jobs. Leigh Creek coal mine that fuelled the power station closed in November 2015, also saw a loss of around 200 jobs[ix]. While the community did not initially receive Federal nor State Government support (according to the UNSW report) it has since been transitioning as one of Australia’s largest-growing renewable energy hubs, with several new projects in development:

- The 275MW Bungala solar photovoltaic (PV) power plant, just outside of Port Augusta, has begun providing power to the grid. Stage One connected to the grid in May 2018 and Stage Two is expected to be completed by early next year. It is expected to produce a combined 220MW of electricity.

- In late 2017 the South Australian Government awarded a contract to SolarReserve for the construction of a $650 million 150-megawatt solar thermal power plant in Port Augusta that will be the largest of its kind in the world. The construction of the power plant is now expected to start in early 2019 and it is anticipated that it will take 30 months to complete once construction starts[x].

- The Port Augusta Renewable Energy Park received development approval in 2016. It will be one of the largest hybrid renewable energy projects in the southern hemisphere, with 59 wind turbines and almost 400 hectares of solar PV panels with a combined generation capacity of 375 MW.

- The 212 MW Lincoln Gap wind farm just outside of Port Augusta, is also expected to create up to 130 jobs with its 59 wind turbines and 10MW grid scale battery storage. Construction began in late 2017 and is expected to be commissioned in late 2018.

GFG Alliance CEO Sanjeev Gupta also has plans for Port Augusta, recently announcing that the world's biggest lithium-ion battery will be built at the town. He also has plans for neighbouring town Whyalla, aiming to use the town’s steelworks to produce steel that can be used as part of gas pipelines. It is expected to produce two million tonnes of steel each year, ramping up to as much as 10 million tonnes.

Gupta also wants to build renewable energy, with the stated aim of making GFG Alliance one of the biggest energy providers in the nation, and as part of that it is also exploring possibilities for a pumped hydro energy storage plant[xi].

Despite some of the commentary in the recent UNSW report, the transition to a new energy system is clearly already underway.

[i] CFMEU calls for transition strategy ahead of coal plant shutdown, The Australian, 30 October 2018

[ii] https://www.theherald.com.au/story/5724959/hunter-power-workers-should-get-orderly-transition-says-new-report/

[iii] http://newsroom.unsw.edu.au/news/business-law/danger-workers-energy-transition-says-report

[iv] https://www.energy.gov.au/sites/g/files/net3411/f/independent-review-future-nem-blueprint-for-the-future-2017.pdf

[v] The Garnaut Climate Change Review, Ross Garnaut, 2008

[vi] Electric vehicles set to bring hundreds of jobs to Victoria's Latrobe Valley, ABC News 31 October 2018

[vii] https://www.energycouncil.com.au/media/14396/3-sea-electric.pdf

[viii] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-04-11/how-the-hazelwood-transition-fund-has-been-spent/9591308

[ix] https://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/climate/south-australian-coalfired-power-station-demolition-nears-completion/news-story/caaed27f56c357ced0419ff7462b9689

[x] https://aurorasolarthermal.com.au/project/faq/

[xi] https://www.whyallanewsonline.com.au/story/5425603/guptas-powerful-plans/

Related Analysis

2025 Election: A tale of two campaigns

The election has been called and the campaigning has started in earnest. With both major parties proposing a markedly different path to deliver the energy transition and to reach net zero, we take a look at what sits beneath the big headlines and analyse how the current Labor Government is tracking towards its targets, and how a potential future Coalition Government might deliver on their commitments.

A farewell to UK coal

While Australia is still grappling with the timetable for closure of its coal-fired power stations and how best to manage the energy transition, the UK firmly set its sights on October this year as the right time for all coal to exit its grid a few years ago. Now its last operating coal-fired plant – Ratcliffe-on-Soar – has already taken delivery of its last coal and will cease generating at the end of this month. We take a look at the closure and the UK’s move away from coal.

Delivering on the ISP – risks and opportunities for future iterations

AEMO’s Integrated System Plan (ISP) maps an optimal development path (ODP) for generation, storage and network investments to hit the country’s net zero by 2050 target. It is predicated on a range of Federal and state government policy settings and reforms and on a range of scenarios succeeding. As with all modelling exercises, the ISP is based on a range of inputs and assumptions, all of which can, and do, change. AEMO itself has highlighted several risks. We take a look.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.