NSW Generation: What impact intervention?

This week the Federal Government announced it would be prepared to step in to have 1000MW of dispatchable capacity built to replace the retiring 1680MW Liddell power station in NSW if the private sector does not “step up”.

On the back of the Liddell taskforce report, completed in April but only just released, the government has set a dispatchable capacity target of 1000MW for the private sector to commit to by the end of April 2021 and have online by the 2023-24 summer. If this doesn’t occur the government intends to intervene to ensure new gas-fired replacement capacity is built.

Affordability and reliability were flagged as key factors for the government’s response. Unsurprisingly, the Liddell taskforce report[i] finds the final impact on prices and reliability will be dependent on market conditions and the willingness of market participants to invest in replacement capacity. The issue is whether the potential for the government to intervene in the market could prove to be counterproductive and impact the decisions of private investors.

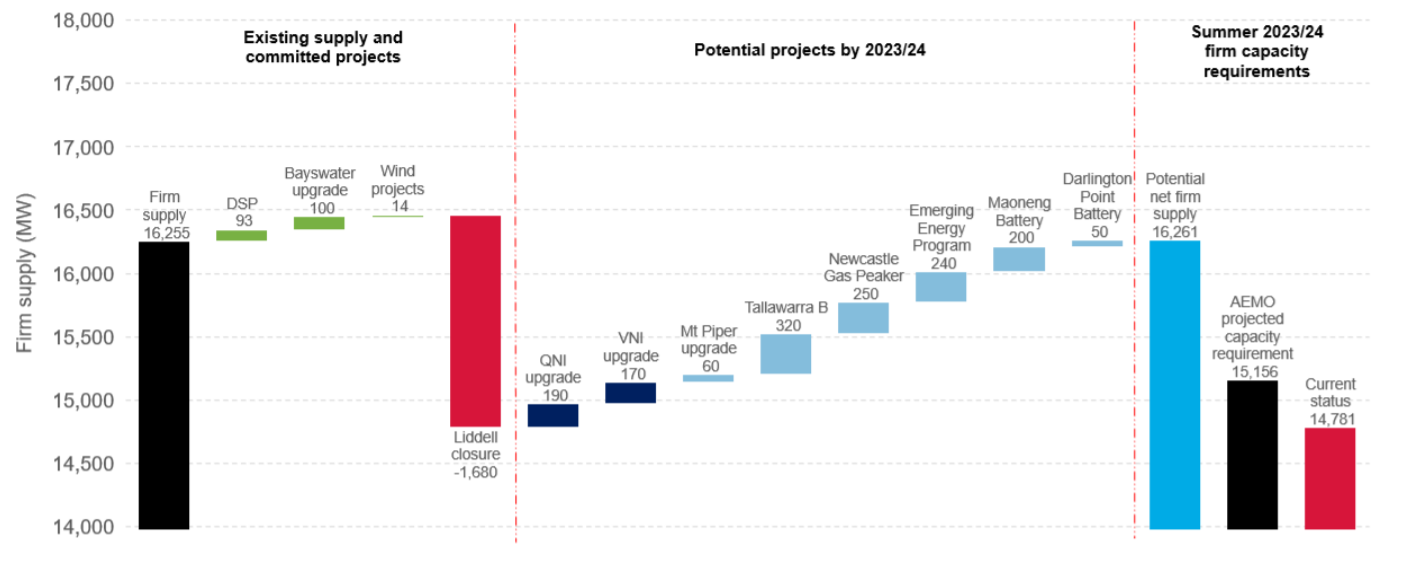

The report also highlights that there is already more than 1000MW of potential and committed new capacity for NSW a shown below.

Figure 1: Committed and Proposed Projects to Replace Liddell

Source: Report of the Liddell Taskforce

In terms of reliability, the Australian Energy Market Operator’s (AEMO) most recent Electricity Statement of Opportunities (ESOO) found that even when considered against a more stringent interim reliability measure (IRM) agreed by COAG, NSW was projected to have a gap of 154MW in 2023[ii]. But this does not include additional supply beyond what has already been committed to being built or transmission options in the market operator’s integrated system plan, and AEMO also noted the announcement of the NSW Government’s support for dispatchable capacity through its Emerging Energy Program was expected to see even the more conservative reliability measure met. The existing reliability standard was not forecast to be at risk until 2029-30, based on a prediction that Vales Point would close.

The Liddell taskforce report also points to government commitments that “may improve price, reliability and security outcomes, including support for upgrades to interconnectors, Snowy 2.0, NSW’s Emerging Energy Program, NSW’s energy retailer procurement process and both governments’ commitment to establish the Central West NSW Energy Zone”.

In terms of prices, average annual spot wholesale prices, according to the Australian Energy Regulator, are at five year lows across all regions[iii] and in Q2 2020 were $45/MWh in NSW[iv]. ASX futures prices through to 2024 are predominantly around $45-$50/MWh with higher variations in the March quarter reflecting summer price spikes[v].

The government’s concern to ensure reliability and affordability is understandable given the challenge of managing the energy transition and exit of coal-fired plants over the next two decades, which is starkly outlined in the Energy Security Board’s (ESB) consultation paper on the post-2025 review.[vi]

It is an issue that needs to be carefully managed. The government has pointed to investment stalling in dispatchable plant. That has coincided with a lack of policy certainty and interventions at both state and federal level – for example, we are yet to see the outcome of the Federal Government’s underwriting generation investment program, while there has been various targets to encourage investment in renewable energy plant.

The ESB notes that structural changes in the energy sector are typically “exacerbated (or caused)” by policy interventions and uncertainty. A key theme to come from stakeholders was the unfavourable effect policy uncertainty had on investment decisions with the ESB reporting, “Participants noted that the risk of government intervention has intensified since 2017, that there have been various interventions at both state and federal levels, and that even discussions and ‘threats’ of intervention may deter investors.”

Part of its work has been to consider current investment signals as well as options, such as real-time prices, so spot prices better reflect the cost of reliable, secure supply and longer duration investment price signals, as a means to address the concerns.

The current National Electricity Market (NEM) is designed to address the issue through pricing that becomes self-correcting - tight supply leading to increased wholesale prices, which signal and incentivise the development of new plant. New capacity reduces pressure on wholesale prices. Mechanisms like the market price cap, as well as retailer management of the price fluctuations through contracting help smooth the outcome for consumers.

Price volatility, however, is not always politically palatable, especially when prices are rising, and increasingly has prompted various government interventions in the market that in turn increases risks for private investors.

As part of its Resource Adequacy Mechanisms (RAM) chapter, the ESB is contemplating ways to “sharpen real time prices” with options such as a scarcity price adder, an operating reserve mechanism or lifting price caps. These are expressly intended to raise real-time prices above what the current market design would deliver. The ESB is effectively saying that as a result of the threat of government intervention putting risk on private investment, prices need a counteracting boost to ensure we do get enough investment for reliability.

But at the same time, the government has described its large intervention as having the express purpose of suppressing future real-time prices. Presumably this will mean the ESB will have to boost prices even more: a seemingly farcical spiral of governments and their institutions driving in different directions.

The issue

The concern about having sufficient dispatchable plant is driven by the fact the NEM is expected to see 15GW of large thermal plant leave during the next 20 years, as plants come to the end of their operational life or become economically unviable due to loss of revenue changes in the way they are required to operate and/or increased operational and maintenance costs.

It is expected to be replaced by 26-50GW of new large scale renewable generation backed by 6-19GW of flexible, dispatchable power.

Plants will be replaced by more flexible, dispatchable capacity like gas peaking plants, pumped hydro and batteries. While the ESB notes that remaining, older thermal plant could gain additional profits by staying in the market following other closures, they can also be expected to need to operate more flexibly and could see significant increases in their operating costs.

Risks from closures

The risks from coal-plant closures are well known but the scale of the impact will depend on the size of the plant and the region where it occurs. For retailers it will depend on their structure. For vertically integrated retailers the impact will depend on whether they are long or short in generation. If they are short of generation they will be exposed to higher wholesale prices when acquiring additional output to meet their load.

Existing mechanisms

There are a range of measures in place to deal with reliability and security of supply risks with a range of other options under assessment, such as resource adequacy mechanisms, two-sided markets and proper valuation of essential system services, such as frequency control.

There are already mechanisms in place to deal with the risk of plant closures. These include:

- The Notice of closure requirements – with generators needing to provide 42 months’ notice to the market. It’s worth noting that in the case of Liddell, AGL Energy provided notice in 2015 with the closure originally slated for 2022, but subsequently extended to 2023.

- The Retailer Reliability Obligation – this requires energy companies and some large energy users to meet reliability levels if gaps in supply are identified by AEMO and confirmed by the regulator. To meet the RRO the obligated parties have to hold contracts or invest directly in generation or demand response to support the system.

- AEMO’s ESOO – which forecasts whether the reliability standard can be met.

- AEMO’s Integrated System Plan – which forecasts what system requirements will be needed over the next 20 years

- Backstop mechanisms – the Reliability and Emergency Reserve Trader mechanism and AEMO’s ability to intervene if there are shortfalls

- A range of medium and short term assessments of resource adequacy.

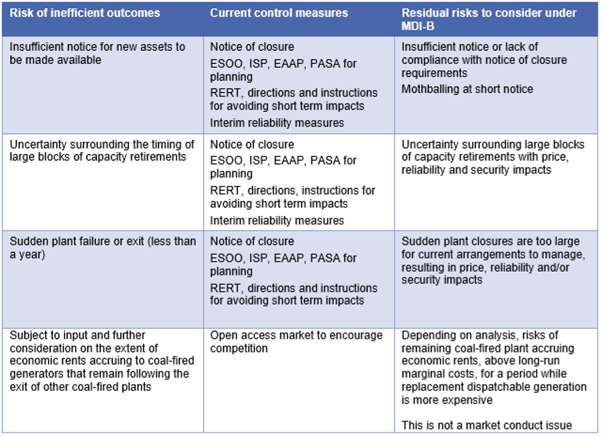

The ESB has identified what it calls residual risks from the exit of coal plants, which are those that the market design may not be able to deal with. These are shown in the following table.

[i] https://www.energy.gov.au/sites/default/files/Report%20of%20the%20Liddell%20Taskforce.pdf

[ii] 2020 Electricity Statement of Opportunities, AEMO, page 9

[iii] https://www.aer.gov.au/news-release/low-wholesale-energy-prices-continue

[iv] https://www.aer.gov.au/system/files/Wholesale%20markets%20quarterly%20Q2%202020%2811441393.1%29.pdf

[v] https://nemriskbulletin.com.au/2020/09/15/promise-or-threat-pms-intervention-in-nsw-electricity-market/

[vi] AER Quarterly prices

Related Analysis

Certificate schemes – good for governments, but what about customers?

Retailer certificate schemes have been growing in popularity in recent years as a policy mechanism to help deliver the energy transition. The report puts forward some recommendations on how to improve the efficiency of these schemes. It also includes a deeper dive into the Victorian Energy Upgrades program and South Australian Retailer Energy Productivity Scheme.

2025 Election: A tale of two campaigns

The election has been called and the campaigning has started in earnest. With both major parties proposing a markedly different path to deliver the energy transition and to reach net zero, we take a look at what sits beneath the big headlines and analyse how the current Labor Government is tracking towards its targets, and how a potential future Coalition Government might deliver on their commitments.

The return of Trump: What does it mean for Australia’s 2035 target?

Donald Trump’s decisive election win has given him a mandate to enact sweeping policy changes, including in the energy sector, potentially altering the US’s energy landscape. His proposals, which include halting offshore wind projects, withdrawing the US from the Paris Climate Agreement and dismantling the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), could have a knock-on effect across the globe, as countries try to navigate a path towards net zero. So, what are his policies, and what do they mean for Australia’s own emission reduction targets? We take a look.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.