Retail energy market intentions

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. Recent commentary has questioned whether Australia’s retail energy markets are as competitive as they could be or whether there should be further regulatory intervention. Exactly what this intervention would achieve remains amorphous, but we know from history what intervention will not achieve. Not so distant past UK and US Government intervention in competitive retail electricity markets should remind us what’s at stake.

Government intervention may fix inefficient markets, in theory

The assumption that a well-functioning competitive market will lead to materially lower prices is a common focal point of discussion for the countries where there has been market interventions. However the nature of competition is that we are never sure what nominal prices should be obtained in a well-functioning competitive market, we can only be confident that they would be materially less than the ones that we have observed. They may not be the prices we want.

In an efficient market, companies can produce goods at the lowest possible cost while individuals can access the goods and services they desire, all while utilising the least resources possible[i]. A market is economically efficient if it has perfect competition and freely available information on the costs and benefits of their transactions[ii]. However, in reality no market will ever be perfectly efficient. If it is not perfectly efficient; is it effectively competitive, or well-functioning?

Governments can use competition policy to make a market more efficient when there is a market failure. Unfortunately the political application of the term market failure has come to incorporate the belief of a market "failing" to provide some desired attribute that is different from efficiency. In the case of retail energy, variations in available price offers are at times considered a "market failure", even though such variation is clearly a sign of a well-functioning competitive market. At any point in time some customers will be aware of, and will respond to, the best offers available, and some will not. For firms this simply represents a challenge that competitors have not yet overcome[iii].

In practice, well-functioning competition is characterised by the process of learning and change, not by full knowledge and equilibrium.

How has government intervention impacted markets around the world?

Can government intervention in a well-functioning competitive market give us the prices we want?

Experience in the UK provides a good example of the challenges of regulating competition. At the end of 2015 Emeritus Professor Stephen Littlechild, a former UK Director General of Electricity Supply and consultant on regulation and competition, was commissioned to assess and report upon the regulation of retail energy markets in the UK and Australia[iv].

The Littlechild report found that interventions in the retail market as a result of concerns that competition had not delivered “enough” for consumers in the UK had not delivered outcomes as intended; that is, the prices they wanted. The UK attempted to get consumers to actively engage in shopping around for their electricity by sharply reducing the number of offers each retailer could make and constraining the shape of the tariff. The outcomes were that:

- Retail margins actually increased;

- Customers lost access to specific tariffs that suited their circumstances[v].

- Customer churn (switching to new retailers for a better offer) fell.

Recently Alistair Phillips-Davies the Chief Executive of SSE, one of Britain’s biggest energy companies, expressed his disappointment at the prospect of facing yet more government intervention in the UK, having just undergone an 18-month investigation by the competition watchdog. This came after UK Prime Minister, Theresa May, promised to step in to fix a market that she claimed was “manifestly not working for all consumers”. This followed the previous market interventions. Phillips-Davies highlighted that “SSE, which has 8.08 million customers, had no choice over its decision to raise electricity prices by 15 per cent as it would have lost money if it had not acted”. He added that regulating prices could have “unintended consequences like killing competition” [vi].

In Australia, the recent Grattan Institute’s report on retail pricing, by its own admission, highlighted that the interventions of increased monitoring of prices, simplification of tariff offers and re-regulation “may not reduce electricity costs.”

The California Crisis

In 1996 California became the first state to deregulate its electricity market, the early stages of retail price deregulation encouraged variety and created cost savings for residential and business consumers. It was a happy coincidence of lower wholesale prices, stable retail prices and the new structure appeared to be working[vii].

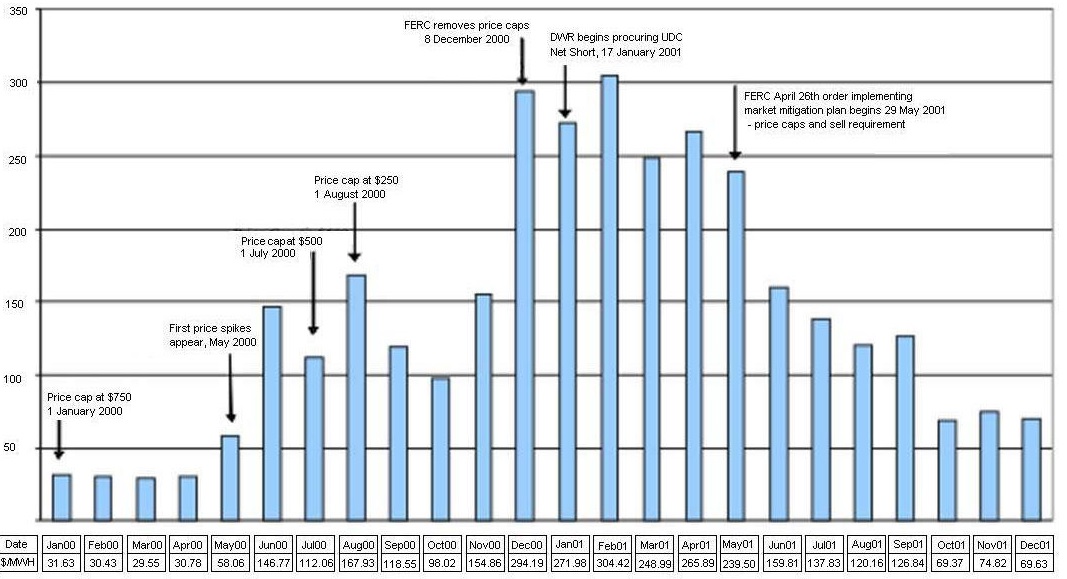

Then in the summer of 2000 a string of events hit the energy market in California. A heatwave sent demand to record highs, lower wholesale prices had meant there was a lack of new power stations being built, there was a drought that decreased the amount of hydro power available to the State. These, combined with the failure of outside power generators to supply enough power to the State, led to wholesale price increases, as shown in Figure 1[viii].

Figure 1: Wholesale prices increasing California 2000 - 2001

Source: California Public Utility Commission, Energy Division, 2001

During the time of the energy crisis the Californian Government took the unusual step to protect consumers from higher prices by putting a cap on the retail price utilities could charge their customers (setting the price they want), while allowing the wholesale price to be determined by the market.

Whilst this held retail prices for a short period, wholesale prices continued to rise, which meant retailers could not pass on the increased costs to consumers because their retail rates were capped. Significant debt for the utilities continued to increase, and as a result a number of utilities filed for bankruptcy in April 2000. The manipulation of the Californian market drove prices to unprecedented levels, up to 20 times their normal value, and as the state had capped retail prices, utilities could not cover these extraordinary costs[ix].

So where to for Australia?

Recently, Gary Banks, the former head of the Productivity Commission, highlighted that government regulation and government failure lie at the heart of the rise in power prices[x]. Speaking about the wholesale market, Banks made the point that blaming the private sector for Australia’s energy problems risks the policy mistakes that caused it being compounded by further policy mistakes.

There are some features of the retail market that are the cause of concern, such as the practice of discounting against your own published higher rate, and losing that discount if you pay late[xi]. But there is no market failure inviting regulatory intervention. Reports such as the Grattan Institute’s[xii] have stopped short of fully considering price re-regulation.

History teaches us that well-functioning competition, not ongoing government and regulatory intervention, is the answer to effectively and efficiently providing the most competitive energy prices for all consumers over the long term.

[i]https://www.boundless.com/economics/textbooks/boundless-economics-textbook/introducing-supply-and-demand-3/government-intervention-and-disequilibrium-49/why-governments-intervene-in-markets-182-12280/

[ii] ibid

[iii] TheGuardian, 2017, “Energy price cap would damage competition, says SSE boss”, << https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/mar/30/energy-price-cap-sse-electricity-gas-theresa-may >>

[iv] Littlechild, S, 2014, “The competition assessment framework for the retail energy sector: some concerns about the proposed interpretation”

[v] ibid

[vi] TheGuardian, 2017, “Energy price cap would damage competition, says SSE boss”, << https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/mar/30/energy-price-cap-sse-electricity-gas-theresa-may >>

[vii] http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/blackout/california/summary.html

[viii] ibid

[ix] ibid

[x] Financial Review, 2017, “Government not market failure to blame for energy crisis”, << http://www.afr.com/news/government-not-market-failure-to-blame-for-energy-crisis-says-gary-banks-20170406-gvf9ra >>

Read more: http://www.afr.com/news/government-not-market-failure-to-blame-for-energy-crisis-says-gary-banks-20170406-gvf9ra#ixzz4dzh24Cv4

Follow us: @FinancialReview on Twitter | financialreview on Facebook

[xi] Even this practice has its roots in Government intervention, as for all practical purposes it is a substitute for a late payment fee; late payment fees being disallowed by government intervention. Presumably the market “failed” by allocating the cost of late payment to the late payer.

[xii] Grattan Institute, 2017, “Price Shock Is the retail electricity market failing consumers?”, March 2017

Related Analysis

2025 Election: A tale of two campaigns

The election has been called and the campaigning has started in earnest. With both major parties proposing a markedly different path to deliver the energy transition and to reach net zero, we take a look at what sits beneath the big headlines and analyse how the current Labor Government is tracking towards its targets, and how a potential future Coalition Government might deliver on their commitments.

Navigating Energy Consumer Reforms: What is the impact?

Both the Essential Services Commission (ESC) and Australian Energy Market Commission have recently unveiled consultation papers outlining reforms intended to alleviate the financial burden on energy consumers and further strengthen customer protections. These proposals range from bill crediting mechanisms, additional protections for customers on legacy contracts to the removal of additional fees and charges. We take a closer look at the reforms currently under consultation, examining how they might work in practice and the potential impact on consumers.

International Energy Summit: The State of the Global Energy Transition

Australian Energy Council CEO Louisa Kinnear and the Energy Networks Australia CEO and Chair, Dom van den Berg and John Cleland recently attended the International Electricity Summit. Held every 18 months, the Summit brings together leaders from across the globe to share updates on energy markets around the world and the opportunities and challenges being faced as the world collectively transitions to net zero. We take a look at what was discussed.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.