How to amp up EVs

This week the Labor Party committed to introducing Australia’s first National Electric Vehicle (EV) Policy as part of its climate change initiatives.

Part of Labor’s rationale is that we lag behind other countries in supporting EVs and hence their take-up. In its policy announcement the ALP said that while EVs have a global market share of around 2 per cent, the share in Australia is only 0.2 per cent.

Key elements of Labor’s proposal are:

- A national EV target of 50 per cent of new car sales by 2030.

- Government fleet EV target of 50 per cent of new purchases and leases of passenger motor vehicles by 2025.

- Growing private EV fleets by allowing businesses to immediately deduct 20 per cent off any new EV valued at more than $20,000.

- Regulatory reforms and COAG coordination. This would include a requirement for all federally funded road upgrades to incorporate EV charging infrastructure, working with states to ensure new and refurbished commercial and residential developments include EV charging capacity, and promoting national standards for EV charging infrastructure.

- Developing an EV Innovation and Manufacturing Strategy.

- Introducing vehicle emission standards of 105g CO2/km for light vehicles.

So how do these measures stack up? Below we look at the uptake of EVs globally and the measures put in place in the leading countries to encourage their further development and increase their market share.

Changing Dynamics of EV Sales Globally

The International Energy Agency has noted that “supportive policies and cost reductions are likely to lead to continued significant growth in the EV market[i]”. And governments internationally have been introducing EV targets (figure 1) and/or are supporting them through government incentives, emission regulations, and low and zero emission vehicle mandates.

Figure 2: Electric vehicle targets of selected markets and how it compares to Labor’s Target

Source: Main Table - Electric Vehicle Council

There were 1.3 million electric vehicles (EVs) sold globally in 2017, to reach 3.1 million sold to date. This was a 57 per cent increase of new EV sales from 2016. Over half of these sales were from China, with around 580,000 EVs sold in 2017 (up 72 per cent from 2016), representing an EV market share of 2.2 per cent and making it the leading EV market. The United States followed with around 280,000 cars sold (up from 160,000 in 2016). It is forecast that sales could rise to up to 4.5 million by 2020 and car makers are now producing around 120 new models annually[ii]. Pure electric vehicles (battery EVs, also known as BEVs) account for 66 per cent of the market.

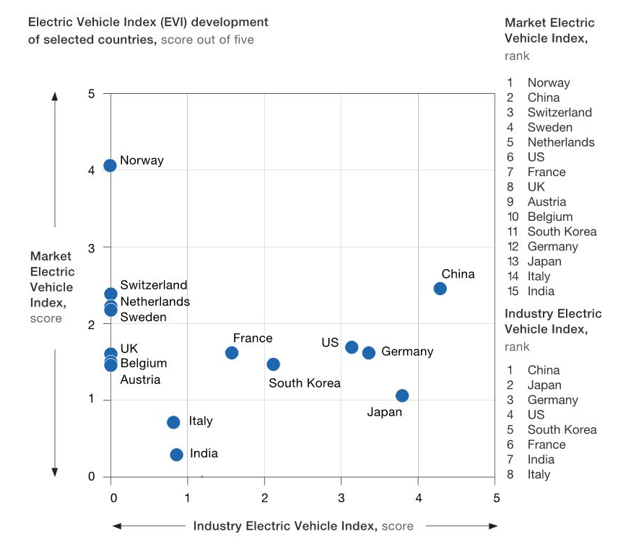

In terms of market share of EVs Norway leads the way (39 per cent of new car sales), followed by Iceland (11.7 per cent) and Sweden (6.3 per cent). McKinsey & Co has created an EV index that shows the national trends and changes over the past few years (see figures 2 and 3 below).

Figure 2: EV Index – National Developments

Source: McKinsey. Industry EV Index refers to manufacturing development; Market EV Index refers to sales.

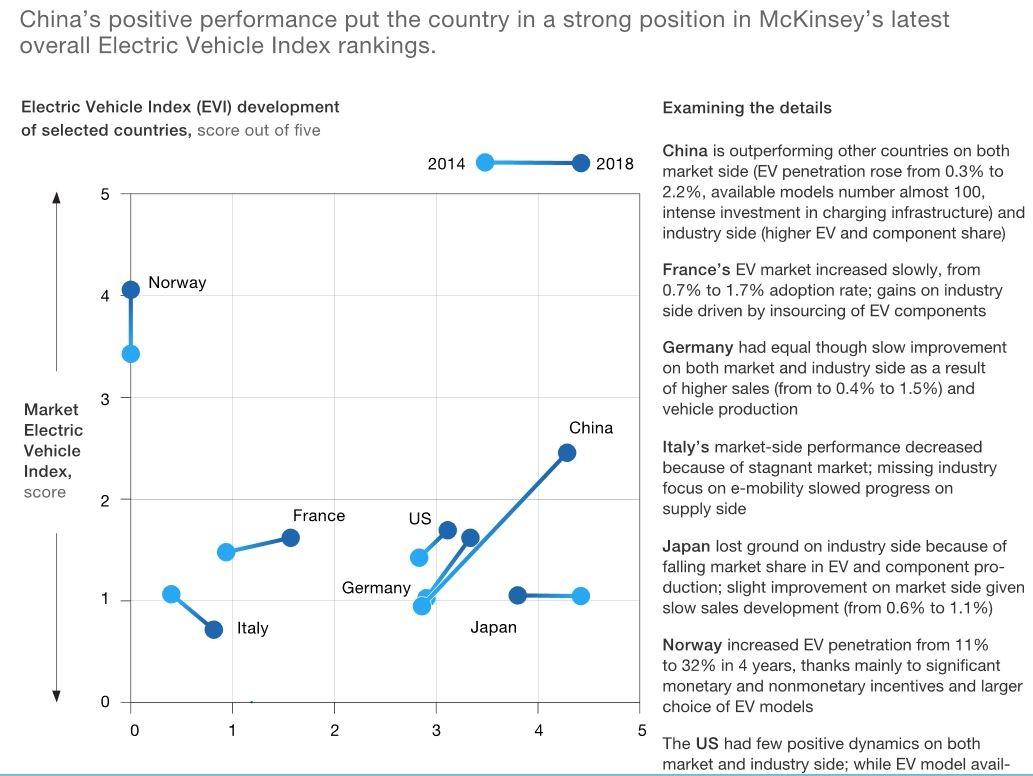

Figure 3: EV Index Development in Period 2014-2017

Source: McKinsey

McKinsey notes that China is outperforming other countries on both the market side and industry development side. It notes that Norway’s increase in EV penetration from 11 per cent to more than 30 per cent in just four years is due to significant monetary and non-monetary incentives and a larger choice of EV models.[iii]

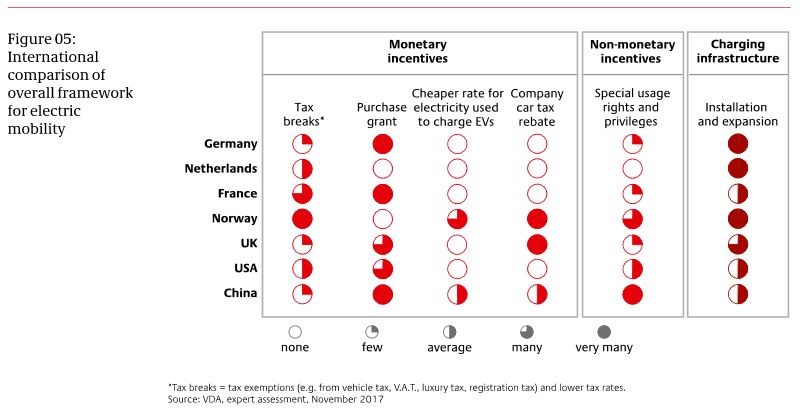

Figure 4 gives a quick look at some of the measures being undertaken by various countries. We then look in more detail at some key countries.

Figure 4: International comparison of overall framework for electric mobility

Source: German National Platform for Electric Mobility

Norway

As a world leader in EV uptake, Norway aims for all new cars sold by 2025 to be zero emission (electric or hydrogen). By the end of 2018, Norway had 200,000 registered BEVs and 10,000 publicly available charging points. According to the Norwegian Electric Vehicle Association 58.4 per cent of new cars sold in March this year were battery-powered. EV’s share of the market in the first three months of 2019 was 48.4 per cent.

Since 1990 incentives have been gradually introduced to accelerate the transition to zero-emission vehicles. Drivers pay low taxes for low and zero emission cars, and high taxes for high emission cars. The current Government has decided to keep incentives for zero emission cars until the end of 2021, incentives include[iv]:

- No purchase/import taxes

- Exemption from 25 per cent VAT on purchase

- No annual road tax

- No charges on toll roads or ferries (1997- 2017).

- Charges were introduced on ferries with upper limit of maximum 50 per cent of full price (2018-)

- Charges on toll roads were introduced with upper limit of maximum 50 per cent of full price (2019)

- Free municipal parking (1999- 2017)

- Parking fee for EVs was introduced locally with an upper limit of maximum 50 per cent of full price (2018-)

- Access to bus lanes (2005-).

- 50 per cent reduction in company car tax (2000-2018).

- Company car tax reduction was lowered to 40 per cent (2018-)

- Exemption from 25 per cent VAT on leasing (2015)

- Fiscal compensation for scrapping of fossil fuel vans when converting to a zero emission van (2018)

- Allowing holders of driver licence class B to drive electric vans class C1 (light trucks) up to 2450 kg (2019).

China

In 2019 China is expected to sell over 2 million EVs (up from 1.1 million in 2018).

China adopted formal policy in 2009 and incentivised government fleet purchases, taxi operators, amongst other fleets. Monetary incentives and purchase tax exemptions were then established for private EV buyers, as well as incentives, such as the use of bus lanes and reduced road tolls[v].

China’s key policy supports for NEVs include reduced taxes, direct subsidies to manufacturers, consumer subsidies, mandated government procurements, and industrial policy. As early as 2008, China’s Ministry of Finance and the Taxation Services General Office announced that NEVs would be exempt from the standard consumption tax on new cars. [12]

China has provided billions of dollars in direct subsidies to manufacturers. For example, Shenzhen-based manufacturer BYD received US$435 million in subsidies between 2010 and 2015. In addition, as part of China’s 2012 “Energy-Saving and New Energy Vehicle Industry Development Plan (2012–2020),” the central government allocated over US$15 billion to support the development of energy-efficient vehicles and NEVs, pilot car projects, and electric vehicle infrastructure. [13]

The government also introduced a consumer subsidy program in 2010 for the purchase of NEVs, providing 60,000 yuan (approximately AUD12,500) and 50,000 yuan (approximately $10,400) per car in subsidies for electric vehicles and plug-in hybrid vehicles. [14]

In September 2017 China finalised a new energy vehicle mandate to take effect for two years from April 2018. As a result from this year car makers are required to have 10 per cent of their sales as new energy vehicles and this will rise to 12 per cent in 2020. This applies to car makers that produce or import 30,000 conventional vehicles annually. If they don’t meet the targets they either have to buy credits from other car makers or pay a fine.

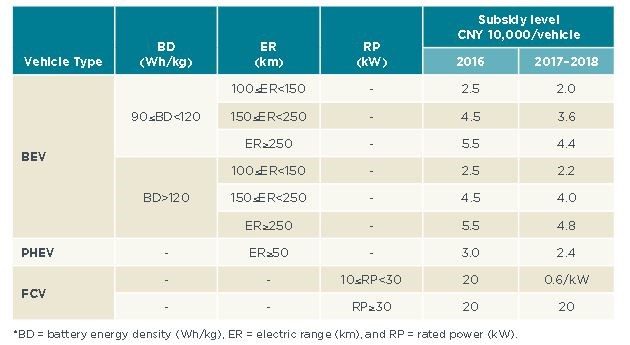

On 1 January 2017 China revised its subsidy program for zero emissions vehicles (BEVs, PHEVs, FCEVs) which are valid to 2020. Subsidies for passenger vehicles reduced by 20 per cent in 2017-2018 from 2016 levels and then reduce by a further 20 per cent in 2019-2020. The subsidies are indexed to car range and battery energy density for EVs. For fuel cell cars the subsidy is linked to power rating. This is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: China National Subsidies for new energy passenger vehicles 2016 and 2017-2018*

*10,000 CNY = AUD2092 / Source: International Council on Clean Transportation

Germany

Cumulated new EV registrations reached 212,834 at 28 February 2019 (54 per cent were BEVs).

Numerous subsidies at EU, federal, state and local level support the further development of electric mobility in Germany. The support measures are based on Germany’s Electric Mobility Act, which came into force in July 2015 and a Cabinet Resolution on 18 May 2016.

Support measures include:

- Environmental subsidy of EUR 4,000 for BEVs and EUR 3,000 for PHEVs. The total is limited to EUR 1.2 billion, provided by the Government and the car makers in equal measure. This runs until mid-2019.

- Investment of EUR 300 million in constructing publicly accessible charging infrastructure, EUR 200 million for rapid charging.

- Procurement program of EUR 100 million.

- Exemption from motor vehicle tax for purely electric vehicles for 10 years.

More than two thirds of all new electric vehicle registrations up to October 2017 were fitted with the special “E” number plate for electric vehicles. The advantages conferred on electric vehicles by the Electric Mobility Act – such as parking privileges, special access rights and special usage rights – create a framework for making electric mobility more attractive at local level.

United States of America

The US’s aim of 3.3 million by 2025 is being driven by nine states. On October 24, 2013, the governors of California, Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Vermont signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) committing to coordinated action to ensure the successful implementation of their state zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) programs. They released a Multi-state action plan in May 2014 and a subsequent plan was released last year[vi].

Key elements/recommendations include support for promotion of ZEVs, development of charging infrastructure, financial and non-financial incentives for the purchase and lease of ZEVs.

The US Internal Revenue Service (IRS)also provides a tax credit is for $2,500 to $7,500 for each new EV. The size of the tax credit is linked to the size of the vehicle and its battery capacity.

France and UK

France and the UK will ban sales of new petrol and diesel cars by 2040. The French Government has set a goal of increasing EV sales fivefold by 2020 and offers incentives such as purchase subsidies and tax-breaks. While last year the UK unveiled their Road to Zero Strategy, a 46-point plan to manage the transition out to 2050. It details how the government will support the transition and reduce emissions from conventional vehicles during the transition. The UK has over 16,000 public charging points, and the government has established a 400 million-pound fund to extend the charging network. UK plug-in vehicles buyers are also eligible for grants of up to 4,500 pounds[vii].

[i] IEA Global EV Outlook 2018

[ii] https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/automotive-and-assembly/our-insights/the-global-electric-vehicle-market-is-amped-up-and-on-the-rise?reload

[iii] ibid

[iv] https://elbil.no/english/norwegian-ev-policy/

[v] https://cleantechnica.com/2019/02/24/china-ev-forecast-50-ev-market-share-by-2025-part-1/

[vi] https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=2ahUKEwiY6bqk7LThAhUcTo8KHf-KCjYQFjAAegQIBRAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.nescaum.org%2Fdocuments%2F2018-zev-action-plan.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0MeREgesFUeJmnbh57Jsud

[vii] https://cleantechnica.com/2018/11/04/8-european-countries-their-ev-policies/

Related Analysis

2025 Election: A tale of two campaigns

The election has been called and the campaigning has started in earnest. With both major parties proposing a markedly different path to deliver the energy transition and to reach net zero, we take a look at what sits beneath the big headlines and analyse how the current Labor Government is tracking towards its targets, and how a potential future Coalition Government might deliver on their commitments.

The return of Trump: What does it mean for Australia’s 2035 target?

Donald Trump’s decisive election win has given him a mandate to enact sweeping policy changes, including in the energy sector, potentially altering the US’s energy landscape. His proposals, which include halting offshore wind projects, withdrawing the US from the Paris Climate Agreement and dismantling the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), could have a knock-on effect across the globe, as countries try to navigate a path towards net zero. So, what are his policies, and what do they mean for Australia’s own emission reduction targets? We take a look.

A farewell to UK coal

While Australia is still grappling with the timetable for closure of its coal-fired power stations and how best to manage the energy transition, the UK firmly set its sights on October this year as the right time for all coal to exit its grid a few years ago. Now its last operating coal-fired plant – Ratcliffe-on-Soar – has already taken delivery of its last coal and will cease generating at the end of this month. We take a look at the closure and the UK’s move away from coal.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.