Green steel and energy exports: How realistic?

The potential for a hydrogen economy to be built around what could become a large-scale, cleaner and cheap energy source is never far from the news.

This week it was flagged again by a Grattan Institute report, “Start with Steel”, that considered the potential economic and social benefits of harnessing Australia’s renewable energy to produce hydrogen for use in an energy-intensive process, like steel making. It is a concept that has also been previously suggested by Professor Ross Garnaut[i].

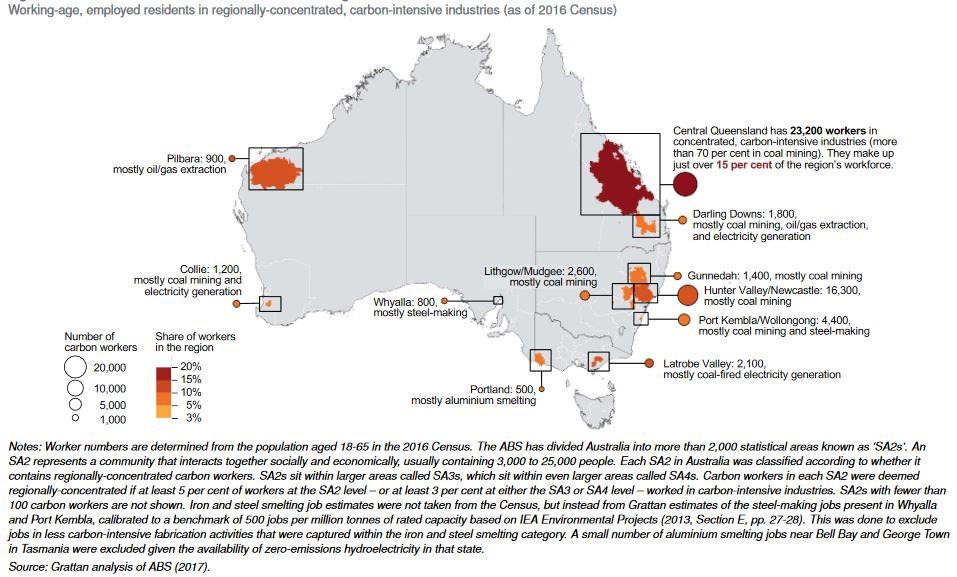

According to the Grattan report Australia has around 100,000 ‘carbon workers’[ii], with about half of them concentrated in geographic areas like central Queensland, the Hunter Valley in New South Wales, the Latrobe Valley in Victoria and the Western Australia’s Pilbara (see Figure 1).”

Figure 1: Communities with significant concentrations of “carbon workers” *view larger image here

These, the report argues, are the most vulnerable workers and regions that would be disproportionately impacted by climate change in the face of future concerted international action to address it.

Grattan argues: “Australia is a major fossil-fuel exporter, so a global move to use low-or zero-emissions energy would present challenges. But it would also present opportunities. Rapid reductions in the cost of wind and solar power over the past decade have turned Australia’s large, sunny, and windy land mass into a globally significant resource. A decarbonising world will enable Australia to diversify beyond its existing carbon-intensive industries, by exporting renewable energy – either as electricity or hydrogen – or low-emissions energy-intensive commodities, such as metals, chemicals, and biofuels.”

Energy exports

Much of the discussion on hydrogen in Australia has been on the potential for it to allow the export of renewable electricity, given our perceived advantages in wind and solar resources, and particularly to Asian countries with limited access to those resources.

When presenting the National Hydrogen Strategy to the COAG Energy Council, Australia’s Chief Scientist, Dr Alan Finkel, said:

“When it comes to capturing and exporting solar and wind electricity by first splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen, clean hydrogen and its derivatives have no equal. Energy importing countries are hungry for hydrogen as part of their emissions reduction agenda, and Australia has the potential to supply much of their needs. We can be the leader in the new industry I call ‘shipping sunshine’”.

The Chief Scientist has also pointed to the potential for hydrogen in transport and to provide the energy for steel making[iii].

Most hydrogen produced today for industry is made from fossil fuels and Dr Finkel has argued that an alternative low-emissions pathway is required. “There are two commercially viable options: splitting water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen, using electricity generated from renewable sources; or refining fossil fuels like coal and natural gas, using carbon capture and storage to mitigate the unwanted emissions”.[iv]

Dr Finkel told the National Press Club earlier this year[v] that producing hydrogen from natural gas or coal, using carbon capture and permanent storage (CCS), would ensure four primary energy sources to meet future needs – solar, wind, hydrogen from natural gas, and hydrogen from coal. He believes that capturing the carbon emitted when manufacturing hydrogen from fossil fuels could be more efficient and economic than CCS for coal-fired generation.

Dr Finkel said the commonly used agents that absorb carbon dioxide in most carbon capture projects, tend to work more efficiently at higher pressures. And the flue gases created when hydrogen is produced from coal gasification are at higher pressures than the flue gases typically created by coal-fired power stations[vi].

Green steel

The Grattan report considers three potential ways for Australia to export its renewable resources:

1. Direct export via underwater cables to neighbouring countries.

2. Producing hydrogen for export as an “energy carrier”.

3. Producing energy-intensive commodities using clean hydrogen.

Exporting electricity through undersea cables, it notes, would raise operational and technical challenges given the long distances involved. To reach even our closest neighbour, Indonesia, would need several thousand kilometres of cable.

There are currently two Australian projects being proposed for large-scale transmission cables to export renewable energy – the Asian Renewable Energy Hub in WA’s Pilbara region, which has been recommended for environmental approval by WA’s EPA[vii] , and the Sun Cable project, which is proposing to export solar power from the Northern Territory to Singapore.

Grattan notes that even if projects like this are ultimately successful, the risks and challenges suggest such exports will still be relatively small compared to other clean energy opportunities.

In terms of hydrogen exports, the Grattan report argues that large-scale hydrogen exports markets don’t currently exist and the product is challenging and expensive to transport and needs to be either liquefied via extreme cooling or converted into a chemical like ammonia. There is also the challenge of doing this being cost competitive.

The report argues that the third approach of using renewable hydrogen to produce “green” steel appears the most likely to create largescale, economically feasible opportunities.

“With globally cost-competitive hydrogen, it will be cheaper to produce green steel here than to ship hydrogen and iron ore to countries such as Japan or Indonesia that have inferior renewable resources.”

Grattan believes it is one of the few economically-credible ways to make the low-emissions steel the world will need if it gets serious about tackling climate change[viii].

The report sees three main ways that renewable resources could underpin the supply of steel to our Asian trading partners (Figure 2):

- Direct reduction of iron ore to iron metal, and the further refining and casting of the iron into a semi-finished steel product for export, all done locally.

- Australia producing direct reduced iron for export with the importing country refining it into steel.

- Australian hydrogen being shipped to the country needing steel, which would use it to produce steel.

Figure 2: Steel pathways *view larger image here

In its report Grattan argues that more jobs are likely to come from Australia using its energy cost advantage to produce low-emissions, energy-intensive commodities for export, particularly given that manufacturing activities are typically more labour-intensive than renewable energy operation.

Conclusion

This latest report flags the potential for the hydrogen economy to decarbonise industrial processes and create export opportunities.

Realising that potential could take decades and according to analysis by Bloomberg New Energy Finance’s Hydrogen Economy Outlook, while the cost of producing hydrogen from renewables is expected to fall demand needs to be created to drive down costs. Additionally a wide range of delivery infrastructure will need to be developed and “that won’t happen without new government targets and subsidies”.

The assessment by the Grattan Institute also comes with the caveat that “these opportunities are not certain and will generally rely on either international policies to reduce emissions, or customers being willing to pay a ‘green premium’. But these opportunities are credible, particularly if the world moves away from fossil fuels.”

[i] Superpower – Australia’s Low-Carbon Opportunity, Ross Garnaut, 2019

[ii] Those working in carbon-intensive industries such as coal mining, oil and gas extraction, fossil fuel electricity generation, cement manufacture and “integreated steel-making” using blast and basic oxygen furnaces. The Grattan report does not define all workers in energy or electricity-intensive industries as carbon workers because fossil fuel energy sources can generally be substituted for low-emissions energy sources.

[iii] ibid

[iv] https://www.industry.gov.au/news-media/australias-hydrogen-potential-a-message-from-the-chief-scientist

[v] The orderly transition to the electric planet, National Press Club Address, 12 February 2020

[vi] “Finkel sees room for renewables and fossil fuels in hydrogen race”, Australian Financial Review, 6 December 2019

[vii] “Environmental tick for WA renewable hub”, The West Australian, 4 May 2020

[viii] “Australians want industry, and they’d like it green. Steel is the place to start”, The Conversation, 11 May 2020

Related Analysis

Certificate schemes – good for governments, but what about customers?

Retailer certificate schemes have been growing in popularity in recent years as a policy mechanism to help deliver the energy transition. The report puts forward some recommendations on how to improve the efficiency of these schemes. It also includes a deeper dive into the Victorian Energy Upgrades program and South Australian Retailer Energy Productivity Scheme.

2025 Election: A tale of two campaigns

The election has been called and the campaigning has started in earnest. With both major parties proposing a markedly different path to deliver the energy transition and to reach net zero, we take a look at what sits beneath the big headlines and analyse how the current Labor Government is tracking towards its targets, and how a potential future Coalition Government might deliver on their commitments.

The return of Trump: What does it mean for Australia’s 2035 target?

Donald Trump’s decisive election win has given him a mandate to enact sweeping policy changes, including in the energy sector, potentially altering the US’s energy landscape. His proposals, which include halting offshore wind projects, withdrawing the US from the Paris Climate Agreement and dismantling the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), could have a knock-on effect across the globe, as countries try to navigate a path towards net zero. So, what are his policies, and what do they mean for Australia’s own emission reduction targets? We take a look.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.