Gas in Australia: Where is it now and where is it going?

Gas reform has been a focus of government over a number of years. The implementation of the current reform process is now concluding, with most initiatives expected to be in place by mid-2020.

Every two years the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) is obliged to report to the COAG Energy Council on the state of liquidity in the wholesale gas and pipeline trading markets. The last review, conducted in August 2018,[1] showed that liquidity is improving, and will continue to do so as further reforms are implemented. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) has also completed a series of reports, making recommendations along the way, with its most recent interim report delivered in July this year. However significant environmental barriers to onshore gas exploration on the east coast remain.

Here we take a deep-dive into the background, current regulatory frameworks and the potential future trends of Australian gas developments.

Background

Reserves

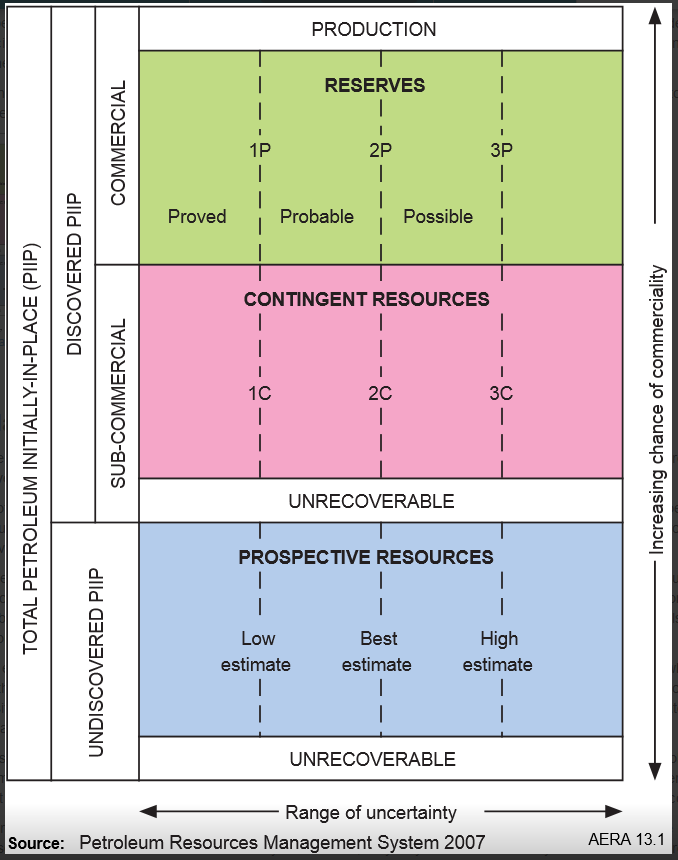

Natural gas is Australia’s third largest energy resource after coal and uranium.[2] Reserves are classified according to their technical and commercial prospects of recovery, as shown in Figure 1 below.[3]

Figure 1: Resources Classification Framework

Source: Geoscience Australia

Proved & Probable (i.e. 2P) Reserves across Australia total approximately 108 exajoules (108,000PJ), of which 39EJ is connected to east-coast markets.[4] The east coast also has a further 30EJ of sub-commercial Proved & Probable Contingent (i.e. 2C) gas resources.[5]

To give an idea of the magnitude of these resources, Australia produces (for domestic consumption and export) approximately 5EJ p.a.,[6] therefore Australia has over 20 years of supply available – without any further exploration and development.

Focusing on the National Electricity Market (NEM), last financial year east coast production was 1.9EJ, therefore again there are more than 20 years’ reserves available. The location of the reserves is set out on the following map.

Figure 2: Natural Gas Reserves & Contingent Resources – Australia, PNG and Timor Leste

Source: EnergyQuest[7]

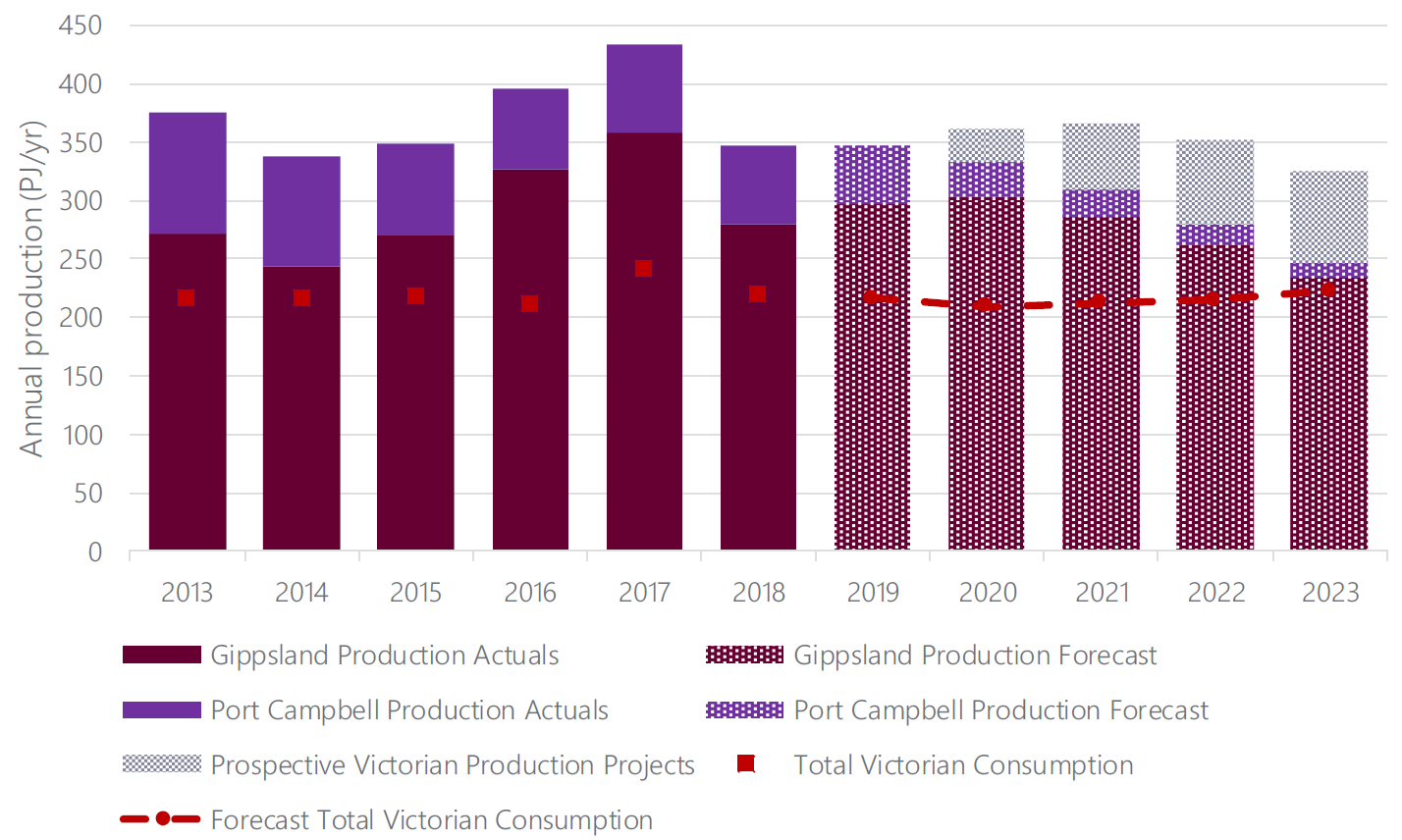

Due to their age, southern gas reserves, predominantly the Gippsland Basin, are declining, as shown in the following graph (figure 3). Nevertheless, within the limits of the Victorian Government’s gas exploration policy, other explorers have commenced offshore development,[8] and these are expected to supplement Victorian production in future years.

Figure 3: Annual Production by Location

Source: AEMO[9]

Pipelines

To bring the gas to load centres, there are a number of major transmission pipelines, as shown in the following map.

Figure 4: Gas Transmission Pipelines

Source: AER[10]

Since gas transmission pipelines have monopoly elements, the sector is subject to varying degrees of regulation, being:

- Full Regulation – where the Australian Energy Regulator (AER) sets a reference tariff for at least one service offered by the pipeline, based on the AER’s assessment of the pipeline’s efficient costs and revenue needs;

- Light Regulation – where the AER arbitrates disputes referred to it by access seekers and monitors pipeline businesses’ compliance with their price disclosure obligations; and

- Part 23 Regulation – where the AER sets guidelines on the disclosure of financial and pipeline use information, and monitors and enforces compliance with these obligations. The AER also establishes a pool of experienced arbitrators to deal with disputes and can appoint an arbitrator if required.

Demand

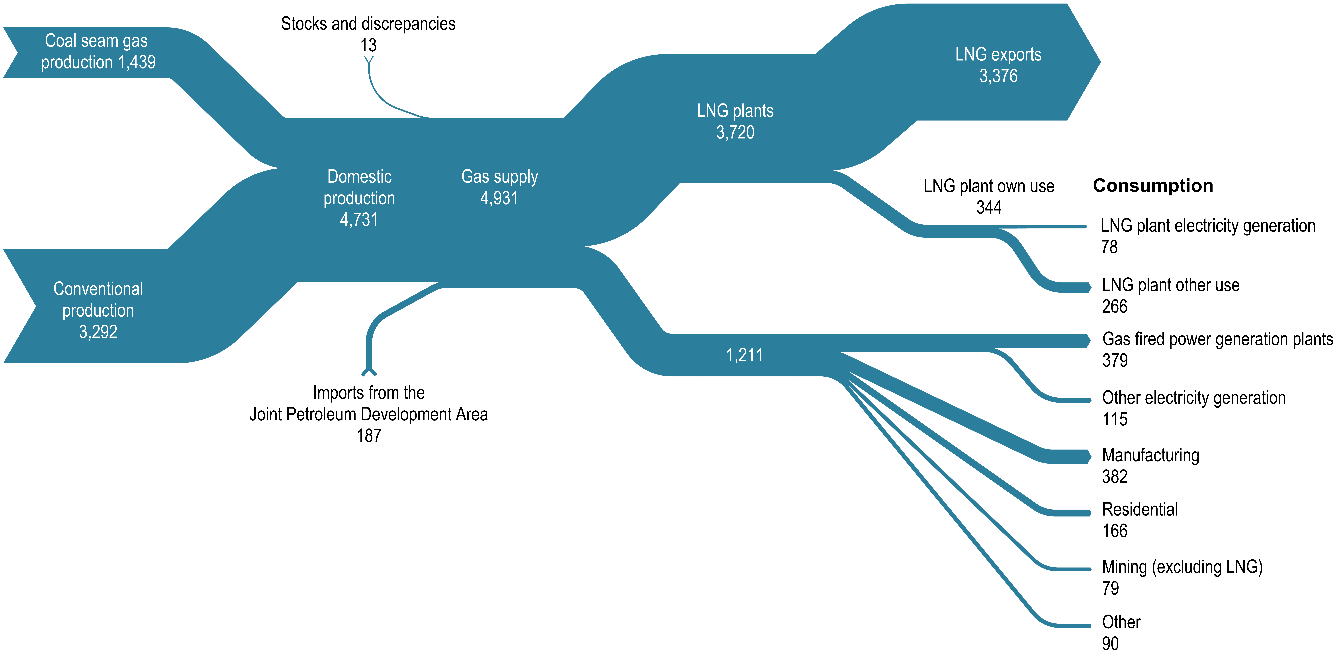

Australia’s national demand is set out in the following diagram.

Figure 5: Australian natural gas flows, petajoules, 2017-18

Source: Department of the Environment and Energy[11]

Over the past ten years, Australia’s east coast gas demand has increased markedly, due to the commissioning of the Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) plants in Queensland.

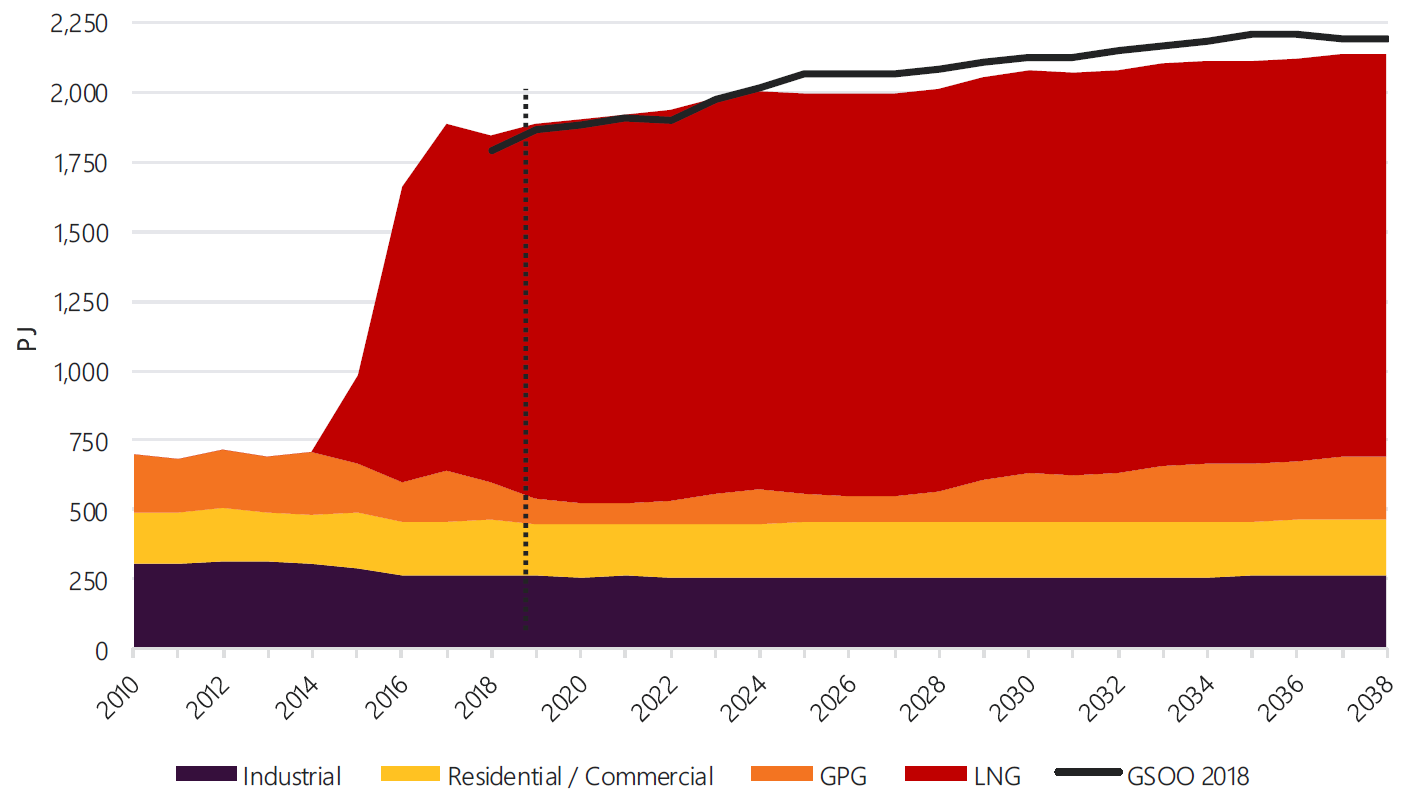

Figure 6: Actual & Forecast Gas Consumption 2010-38, All Sectors, Neutral Scenario

Source: AEMO[12]

Underlying east-coast gas demand has remained flat, with the only material variation being the consumption of gas in NEM gas-fired generation which is heavily affected by both gas price and electricity conditions. After recent declines, GPG is predicted to increase over coming years.

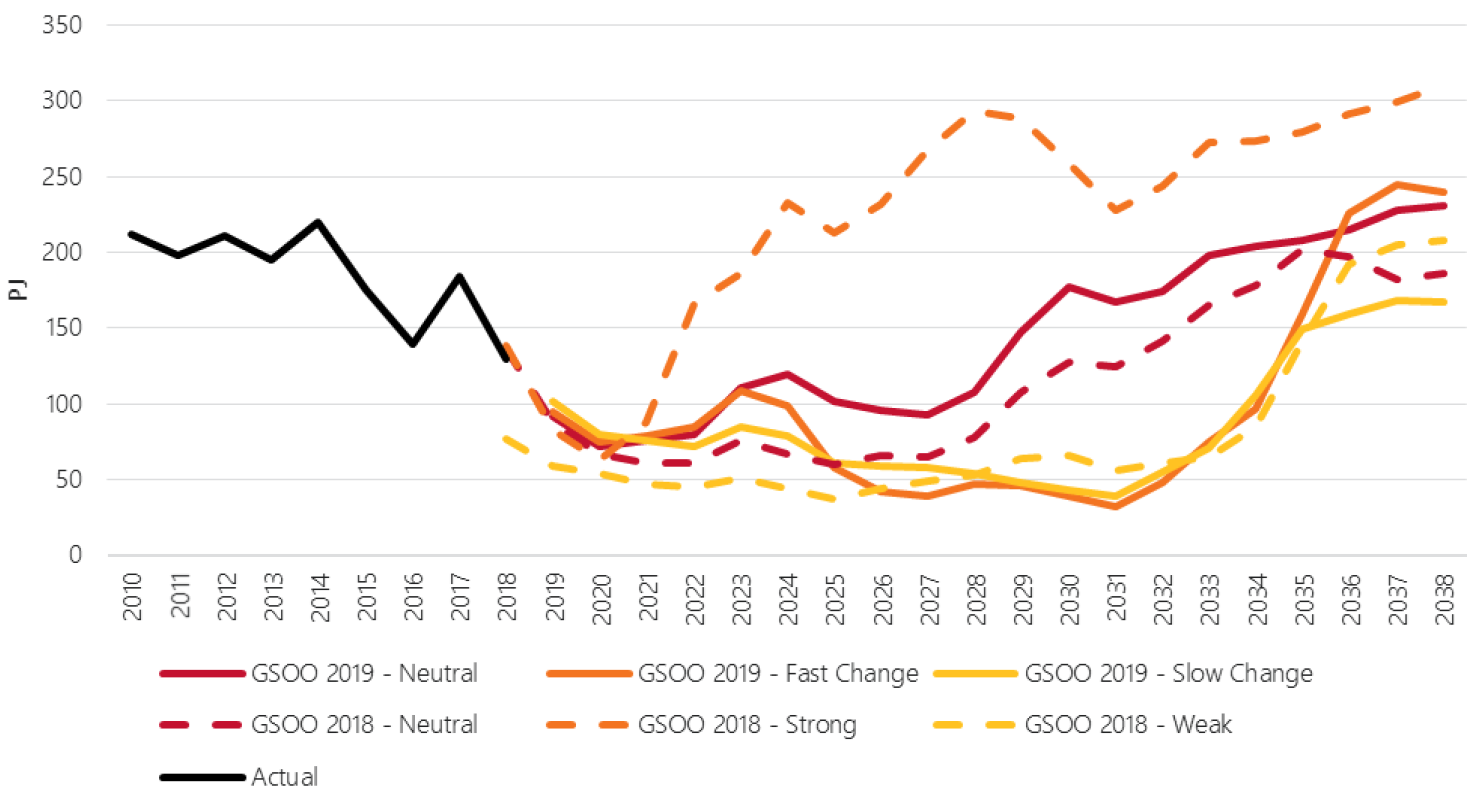

Figure 7: GPG Annual Consumption Actual & Forecast, 2010-38, All Scenarios

Source: AEMO[13]

Gas prices

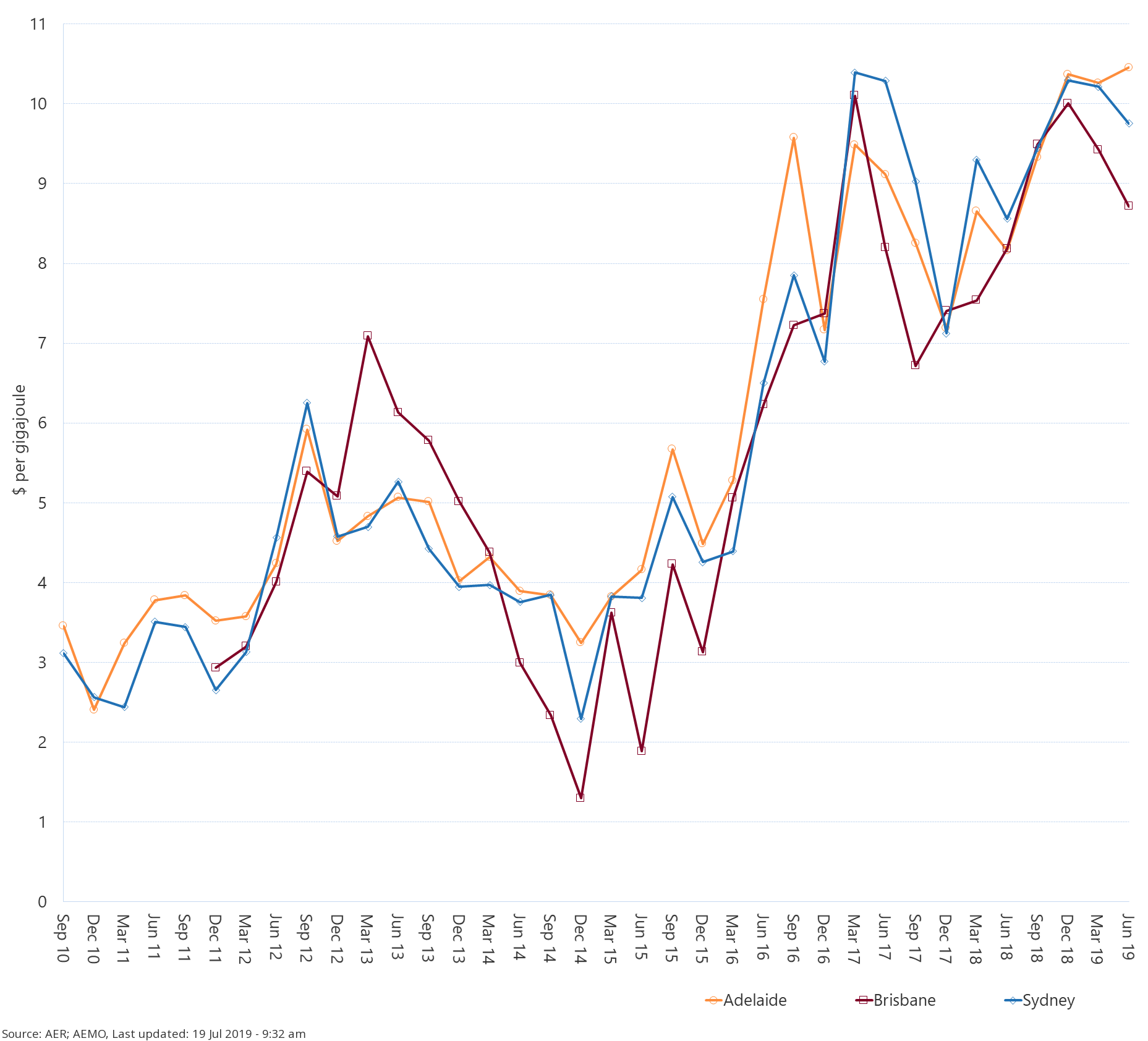

Given the level of transparency in the market, reporting of gas prices is limited, and commentators generally report the Short-Term Trading Market prices as a proxy, noting that they may not be reflective of longer-term arrangements.

Figure 8: STTM - Quarterly Prices

Source: AER[14]

Regulatory framework

Gas Market Reform

Gas reform has been a focus of government over a number of years. In December 2012 the Standing Council on Energy and Resources agreed to an Australian Gas Market Development Plan, and this was followed in December 2014 by the COAG Energy Council releasing its Australian Gas Market Vision,[15] which built on existing reforms and set out 12 specific outcomes, broken into 4 work streams, as follows:

- Encouraging competitive supply;

- Enhancing transparency and price discovery;

- Improving risk management; and

- Removing unnecessary regulatory barriers.

The Australian Gas Market Development Plan was updated in December 2015,[16] and superseded in August 2016 by the COAG Energy Council’s Gas Market Reform Package,[17] which responded to the ACCC’s 2016 East Coast Gas Inquiry[18] and the AEMC’s East Coast Wholesale Gas Market and Pipeline Frameworks Review[19] by establishing a dedicated Gas Market Reform Group to focus on 4 priority areas (gas supply, market operation, gas transportation and market transparency) and implement 15 reform measures, including establishing 2 primary trading hubs and a gas transportation capacity market.

The August 2017 Energy Council Gas Supply Strategy[20] is a successor to the December 2015 Australian Gas Market Development Plan and was amended by the Council to recognise onshore conventional gas more explicitly, and to include offshore gas and underground gas storage, as part of a more holistic approach to national gas supply, and to meet community expectations in regard to the use of resources. It suggested four focus areas for the states and territories to collaborate, including improving information on gas reserves and production potential, improving public information and improving the regulatory frameworks for gas development.

The implementation of the reform process is now concluding with most initiatives expected to be in place by mid-2020.

Every two years the AEMC is obliged to report to the COAG Energy Council on the state of liquidity in the wholesale gas and pipeline trading markets. The last review, conducted in August 2018,[21] concluded that liquidity is improving, and will continue to do so as further reforms are implemented. The next review will be conducted mid-2020.

ACCC gas inquiries

On 13h April 2015 the Minister for Small Business,Bruce Billson, commissioned the ACCC to hold a public inquiry into the competitiveness of wholesale gas prices and the structure of the upstream, processing, transportation, storage and marketing segments of the east coast gas industry.

The 2016 East Coast Gas Inquiry[22] made a number of findings, including:

- The domestic gas market is now more exposed to international oil prices;

- Regulatory restrictions will affect future supply;

- The supply outlook in the east coast gas market remains uncertain to 2025 and beyond;

- Different pricing dynamics apply in Queensland and the southern states;

- Gas reservation policies should not be introduced;

- Market developments compel the ACCC to revisit Gippsland Basin Joint Venture (GBJV) joint marketing arrangements;

- There is evidence of pipeline monopoly pricing giving rise to higher prices and economic inefficiencies;

- The gas pipeline access regime should be strengthened;

- The gas market is opaque and inflexible and is not signalling expected supply problems effectively; and

- Transportation capacity and hub services can be further unlocked to increase efficient use.

This report spurred the gas market reform detailed above, and in April 2017 the Government directed the ACCC to conduct a wide-ranging inquiry into the supply of and demand for wholesale gas in Australia, as well as to publish regular information on the supply and pricing of gas for the next three years. On 6 August 2019 the Government extended the ACCC Gas Inquiry to December 2025.[23]

The ACCC has completed a series of interim reports,[24] making recommendations along the way, and has published a number of reports on individual topics, such as International Prices.[25]

The most recent interim report, July 2019,[26] reported that:

- Sufficient gas supply is expected in 2020 to meet forecast demand in the East Coast Gas Market;

- Many C&I users will pay at least $10/GJ for supply in 2020;

- Recent price offers have fallen in Queensland with declining netback, but this has not occurred in the south; and

- Australian delivered gas prices compared to prices paid overseas are:

- lower when compared with LNG-importing countries; but

- higher when compared with LNG-exporting countries.

The Interim Report also indicated that the ACCC will, over the course of the Inquiry, conduct a closer review of:

- the retail gas market to more fully understand the drivers of high margins, including potential barriers to suppliers entering or expanding their operations in retail markets;

- the ability of shippers to access regional pipelines;

- the effect that the capacity trading reforms are having on the demand for transportation services and the behaviour of shippers and pipeline operators; and

- the cost reflectivity of prices charged by pipeline operators.

Reservation policies

WA has maintained a domestic gas reservation policy since 1979 when it helped underwrite the development of the North-West Shelf LNG project. It currently requires new developments to set aside 15 per cent of their LNG productions for domestic sale, and to offer such gas in good faith to domestic consumers. Given the large size and low costs of the conventional WA LNG export projects, this creates conditions for domestic WA gas to be valued below international prices.

Queensland has its own domestic gas reservation policy in the form of the Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act (Qld) 2004. It reserves particular petroleum leases solely for supply into the Australian market. The small size of the reservation and the relative development costs mean that the influence upon domestic prices could not replicate the WA situation.

In consideration of such policies, the ACCC’s East Coast Gas Inquiry found that, “[t]he gas supply issues … would not be fixed by a reservation policy; in fact they could be worsened if a reservation policy was enacted which artificially depressed prices in the short term and discouraged investment in new gas supply, thus reducing the likelihood of required supply diversity.”[27]

Its recommendation was that “gas reservation policies should not be introduced, given their likely detrimental effect on already uncertain supply”.[28]

Australian Domestic Gas Security Mechanism

On 1 July 2017 the Commonwealth Government established the Australian Domestic Gas Security Mechanism (ADGSM) to be in place until December 2022, in response to fears of possible shortfalls, highlighted by AEMO’s 2017 GSoO.[29] The ADGSM allows the Minister for Resources to restrict LNG exports if the Minister has reasonable grounds to believe that there will not be a sufficient supply of natural gas for Australian consumers during the year unless exports are controlled, and that exports of LNG would contribute to that lack of supply.[30] It does not have a price trigger.

At this time the ADGSM has not been invoked, however additional domestic supply has been made available from the exporting companies since the 2017 outlook under the Gas Supply Guarantee (discussed below), arguably influenced by this threat.

On 6 August 2019 the Government announced:[31]

- it was bringing forward its 2020 review of the ADGSM so it would be completed by the end of September and that a price trigger would be considered;

- it was considering options to establish a prospective national gas reservation scheme, with the study to be concluded by February 2021; and

- it would work to improve supply by:

- extending the ACCC’s role in monitoring and publishing data on the gas market until December 2025;

- engaging with LNG plants to explore whether some of their processes could be electrified, to free up more gas for domestic use;

- engaging with the manufacturing sector to explore opportunities to lower gas costs and reduce demand through increased energy efficiency and electrification measures;

- considering the feasibility of establishing mechanisms to facilitate collective bargaining and improve the negotiating position of large industrial users for gas supply; and

- seeking COAG Energy Council agreement to direct the Australian Energy Market Commission to advise on further steps that could be taken to accelerate the establishment of a more liquid wholesale gas market.

Gas Supply Guarantee

In March 2017, Production Facility Operators and Pipeline Operators made commitments to the Commonwealth Government to make gas available to meet peak demand periods in the National Electricity Market. The Gas Supply Guarantee is a mechanism developed by the gas industry to facilitate the delivery of these commitments.[32]

The mechanism took effect on 1 December 2017 and expires 31 March 2020.

Production Facility Operators propose to meet this commitment by making additional gas supply available to Gas Generators through Facilitated Markets or contractual arrangements during peak NEM demand periods, while Pipeline Operators propose to meet this commitment through:

- new interruptible agreements for shipping additional gas supply;

- where possible, coordinating additional transfer and delivery of gas between pipelines; and

- where possible, transporting and making available additional delivery of gas to Gas Generators.

Gas market transparency

Increased gas market transparency has been advocated by the COAG Energy Council and the ACCC since 2012. Most recently, in its July 2019 Interim Report the ACCC stated that increased transparency is to be encouraged to facilitate market liquidity, and proposed a series of measures in its Measures to improve the Transparency of Wholesale Prices in the Gas Market – ACCC Recommendations Report.[33] These included expanding its monthly LNG netback price series and reporting on the wholesale gas prices payable by domestic gas users to producers and retailers for contracts longer than 12 months’ duration.

Environmental barriers to exploration

There are significant environmental barriers to onshore gas exploration in the east-coast.

NSW has does not have commercial conventional natural gas resources available, and has relied on coal seam gas for indigenous supply, however new developments, notably Santos’ Narrabri development, have been stymied by “the toughest coal seam gas regulations in Australia”.[34] These regulations include development oversight by a Land and Water Commissioner, banning the use of BTEX chemicals and evaporation ponds, codes of practice on coal seam gas exploration, and referrals to the NSW Minister for Primary Industries and the Commonwealth Independent Expert Scientific Committee for advice on water impacts. The Environment Protection Authority is the lead regulator.

In contrast, NT conducted a “Scientific Inquiry into Hydraulic Fracturing”,[35] and concluded that onshore gas exploration, drilling and fracking can occur in designated zones, subject to environmental conditions. It is now developing regulations for production.

Victoria, however, has an onshore conventional gas moratorium in place until 30 June 2020, and an ongoing unconventional gas ban.[36]

Future Trends

In the future the gas supply-demand balance may be affected by three possible, major influences.

Declining gas consumption

As discussed above, despite recent increases in gas use as a result of LNG exports and population growth, underlying gas consumption has reduced in domestic and commercial & industrial sectors. Domestic consumption has been reducing due to the displacement of gas for heating and hot water by electricity, as a result of the ready availability of solar panels for self-generation and local requirements for energy efficiency measures in new homes, although this has been partially offset by increases due to population growth. Industrial usage has been most affected by declines in Australian manufacturing, according to the media and EUAA as a result of cripplingly high gas prices, but there are other influences such as labour costs, local demand for products, the exchange rate and international competitiveness which have affected these companies’ decisions.

In time there may be pushes to reduce gas consumption in order to reduce carbon emissions. The ACT Government has declared, in its quest for zero emissions by 2045, that it will discourage the use of natural gas in both residential and commercial uses by removing the mandated requirement for gas connection in new suburbs, supporting gas to electric appliance upgrades and transitioning to all-electric new builds.[37]

Fluctuations in the use of gas for generation

Gas-fired generation accounted for 7.6 per cent of the NEM’s generation last financial year, but has varied over the past ten years, as shown in Figure 7 above. As the NEM’s generation mix changes, this proportion may change, with an accompanying variation in gas consumed.

Hydrogen

In December 2018 the COAG Energy Council established a Hydrogen Working Group, chaired by the Chief Scientist, Dr Alan Finkel AO, to develop a National Hydrogen Strategy to:

- build a clean, innovative and competitive hydrogen industry; and

- position Australia’s hydrogen industry as a major global player by 2030.

As currently formed, the strategy proposes developing renewable hydrogen,[38] which will foster the production of hydrogen for:

- export;

- displacement of natural gas in local distribution (initially by comingling, but later by full replacement); and

- use in hydrogen fuel-cell powered vehicles.

Conclusion

While gas reform has been a key focus, significant barriers to gas exploration on the east coast remain. Removing unnecessary regulatory burdens and lifting restrictions on exploration may provide the right set of conditions for industry to explore and develop new gas resources. The role of gas will remain dependent on its competitive position as a fuel, competing on price and sustainability, and lifting restrictions will assist in this regard.

[1] Australian Energy Market Commission, Gas Market Liquidity Review Final Report, 26th June 2018

[2] Source: https://aera.ga.gov.au/#!/gas

[3] Source: https://aera.ga.gov.au/#!/resource-classification

[4] EnergyQuest, EnergyQuarterly – September 2019 Report, 5th September 2019, p.71

[5] Reserves represent that part of resources which are commercially recoverable and have been justified for development, while contingent resources are less certain because some significant commercial or technical hurdle must be overcome prior to there being confidence in the eventual production of the volumes.

[6] EnergyQuest (op.cit.), p.110

[7] Ibid., p.74, Figure 25

[8] See 4.6 Environmental Barriers to Exploration

[9] Australian Energy Market Operator, Victorian Gas Planning Report, March 2019, p.35, Figure 17

[10] Australian Energy Regulator, State of the Energy Market 2018, December 2018, p.223, Figure 5.1

[11] Department of the Environment and Energy, Australian Energy Update 2019, September 2019, p.10, Figure 2.3

[12] Australian Energy Market Operator, Gas Statement of Opportunities for Eastern and South-Eastern Australia, 28th March 2019, p.17, Figure 4

[13] Ibid., p.27, Figure 12

[14] https://www.aer.gov.au/wholesale-markets/wholesale-statistics/sttm-quarterly-prices

[15] COAG Energy Council, Australian Gas Market Vision, 11th December 2014

[16] COAG Energy Council, Gas Market Development Plan, December 2015

[17] Available at http://www.coagenergycouncil.gov.au/publications/coag-energy-council-gas-market-reform-package

[18] Australian Competition & Consumer Commission, Inquiry into the East Coast Gas Market, April 2016

[19] Australian Energy Market Commission, East Coast Wholesale Gas Markets and Pipeline Frameworks Review – Stage 2 Final Report, 23rd May 2016

[20] COAG Energy Council, COAG Energy Council Gas Supply Strategy, 4th December 2015 (revised August 2017)

[21] Australian Energy Market Commission, Gas Market Liquidity Review Final Report, 26th June 2018

[22] Australian Competition & Consumer Commission (2016),

[23] The Hon Josh Frydenberg MP & Senator the Hon Matthew Canavan, Joint Media Release, 6th August 2019, available at https://minister.environment.gov.au/taylor/news/2019/government-acts-deliver-affordable-reliable-gas

[24] Available at https://www.accc.gov.au/regulated-infrastructure/energy/gas-inquiry-2017-2020

[25] S&P Global – Platts, Study on Global Natural Gas Prices to End-Users for Australian Competition & Consumer Commission, June 2019

[26] Australian Competition & Consumer Commission, Gas Inquiry 2017-2020 Interim Report, July 2019

[27] Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2016), p.68

[28] Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2016), p.20, Recommendation 2

[29] Australian Energy Market Operator, Gas Statement of Opportunities for Eastern and South-Eastern Australia, 9th March 2017

[30] Customs (Prohibited Exports) (Operation of the Australian Domestic Gas Security Mechanism) Guidelines 2017

[31] https://www.minister.industry.gov.au/ministers/canavan/media-releases/government-acts-deliver-affordable-reliable-gas

[32] https://www.aemo.com.au/Electricity/National-Electricity-Market-NEM/Emergency-Management/Gas-Supply-Guarantee

[33] Australian Competition & Consumer Commission, Measures to improve the Transparency of Wholesale Prices in the Gas Market – ACCC Recommendations, 2019

[34] https://www.planning.nsw.gov.au/Policy-and-Legislation/Mining-and-Resources/Coal-Seam-Gas

[35] Available at https://frackinginquiry.nt.gov.au/

[36] https://earthresources.vic.gov.au/geology-exploration/oil-gas/restrictions-on-onshore-gas

[37] Australian Capital Territory Government, ACT Climate Change Strategy 2019-25, 2019, p.6

[38] i.e. hydrogen produced by the electrolysis of water, the power source for which is renewable energy

Related Analysis

Winter Bills: Is it cheaper to heat your house with gas or electricity?

As gas and electricity prices continue to fluctuate across Australia’s east coast, households and businesses are facing rising winter energy costs and growing uncertainty. Seasonal demand, household gas consumption, and the efficiency of electric heating systems, particularly when paired with rooftop solar, are playing an increasingly important role in shaping energy bills. Drawing on data from the Australian Energy Council’s Solar Report Q2 2025, this article explores how these factors affect costs and highlights potential savings for households of different sizes.

The energy transition and power bills: Why aren’t they cheaper?

With energy prices increasing for households and businesses there is the question: why aren’t we seeing lower bills given the promise of cheaper energy with increasing amounts of renewables in the grid. A recent working paper published by Griffith University’s Centre for Applied Energy Economics & Policy Research has tested the proposition of whether a renewables grid is cheaper than a counterfactual grid that has only coal and gas as new entrants. It provides good insights into the dynamics that have been at play.

The gas transition: What do gorillas have to do with it?

The gas transition poses an unavoidable challenge: what to do with the potential for billions of dollars of stranded assets. Current approaches, such as accelerated depreciation, are fixes that Professorial Fellow at Monash University and energy expert Ron Ben-David argues will risk triggering both political and financial crises. He has put forward a novel, market-based solution that he claims can transform the regulated asset base (RAB) into a manageable financial obligation. We take a look and examine the issue.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.