Dunkelflaute: Dealing with renewable growth in the grid

Around 8.5 per cent of Australia’s electricity generation now comes from intermittent renewables, according to the Clean Energy Australia 2016. This is comprised of 4327MW of wind generation, 5480MW of rooftop solar PV and 319MW of large scale solar[i]. This year a ramp up in investment to meet the Renewable Energy Target will see around 3500MW of new intermittent generation enter the market.

The falling cost of installing solar and wind and the task of rebuilding a lower emissions grid is likely to require continued investment in these intermittent technologies over the coming decade. But what are the effects of this and how do we manage the Dunkelflaute?

Dunkelflaute is the German term for the cold, dark and windless winter months where there is almost no output from the nation’s 93GW of installed wind and solar capacity (47 per cent of total German generation capacity)[ii]. South Australia got its first taste of Dunkelflaute this time last year when cold weather (higher demand) combined with low wind and solar output (reduced supply) drove sharp increases in wholesale electricity prices.

The high price events at the time were the market doing its job – signalling peaking plants to enter the market to prevent blackouts. But these events also act as a warning for the market operator about how to manage Dunkelflaute events into the future. In Germany the shortfall is met by increased output from coal, gas and nuclear generators and by importing from neighbouring countries. What will we do?

Generator Reliability Obligation (GRO)

A key tenet of the package of reforms proposed in the Finkel Review is the Generator Reliability Obligation (GRO). This will require new intermittent renewable generation in some parts of the grid to also provide new dispatchable capacity as determined by the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO). This requirement will vary from region to region and presumably change over time as new generation enters and old generation exits. The new dispatchable capacity could be contracted separately to the renewables project, allowing a range of commercial arrangements. It also does not prescribe specific technologies, so in the future we could see renewables bundled with a range of complementary technologies to meet regional system security requirements.

Producing strategic reserve

The Finkel Review flagged the idea of an expanded role for strategic reserve, where AEMO was given the power to contract for a targeted level of capacity held in reserve outside the market. This capacity could take the form either of demand response or out of market generation/capacity. The demand response component of this would either augment or replace the existing Reliability and Emergency Reserve Trader (RERT) mechanism. Currently AEMO is looking to procure more than 600MW of RERT in Victoria for the summer of 2017-18 and an additional 70 MW in South Australia.

Day ahead markets

A day ahead market is, as the name suggests, a market where generators have the opportunity to trade volumes of electricity for each interval in the following day (often based on fuel, such as gas, availability). A generation dispatch schedule is then developed from these trades, based on expected real-time demand. While this market has the benefit of reasonably accurate weather forecasting due to its proximity to the day of generation, the management of the increased penetration of intermittent renewables in the dispatch schedule is usually augmented by a real time balancing or an intraday market which allows for variations in wind speed and cloud cover. The combination of day ahead markets with intraday markets may enable more efficient bidding of capacity and reduce price volatility.

AEMC’s power system security review

This week the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) released its proposed rule changes to stabilise the grid in relation to frequency management and system strength in response to increased intermittent generation entering the market. The changes will require networks to contract for minimum levels of inertia where shortfalls are identified by AEMO to maintain system strength. They also will give AEMO more tools to manage inertia and frequency to maintain system security.

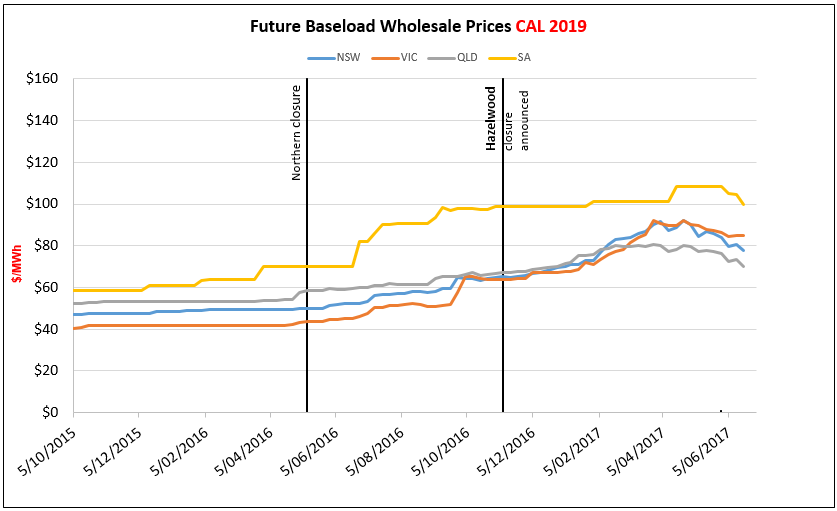

The effect of big renewables on forward prices

The big wave of wind and solar to enter the NEM as retailers meet the 2020 RET target is predicted to provide downward pressure on wholesale prices. This is seen by analysts, including Simon Chan from Bank of America Merrill Lynch, as a key contributing factor to easing forward contract prices for CY19.

Source: ABS

In analysis published this week Chan argues that when total renewables output is greater than 4000MW in the NEM, wholesale prices average around $85/MWh, whereas when renewables output falls below 3000MW, wholesale prices average $102/MWh[iii]. He further contends price volatility may decrease with increased wind investment outside of South Australia and increased deployment of large-scale solar. This is because there is a negative correlation between the average wind output in SA and Victoria and NSW. He argues solar output is more predictable and less likely to increase price volatility.

Average wind output across a 24-hour period (MW) – SA, NSW, Vic and Tas – June ’15 to June ‘17

Source: Bank of America Merrill Lynch

These are average prices and average outputs. It doesn’t mean that another 4GW of renewables spread around the NEM will be a complete antidote to Australian Dunkelflaute. Certainly our winters are not as still, dark and long as Europe. But then our summers are also more superheiß and both the NEM and the South West Interconnected System (SWIS) will have to solve for this without being able to rely on abundant international interconnection.

[i] Clean Energy Australia 2016, Clean Energy Council

[ii] EEI Informer July 2017, Fraunhofer ISE www.energy-charts.de

[iii] Australian Utilities, Downwards from here, Chan, S, Berry, L, Spence, M, Band of America Merrill Lynch, Equity 127 June 2017

Related Analysis

Nuclear Fusion Deals – Based on reality or a dream?

Last week, Italian energy company ENI announced a $1 billion (USD) purchase of electricity from U.S.-based Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS), described as the world’s leading commercial fusion energy company and backed by Bill Gates’ Breakthrough Energy Ventures. CFS plans to start building its Arc facility in 2027–28, targeting electricity supply to the grid in the early 2030s. Earlier this year, Google also signed a commercial agreement with CFS. These are considered the world’s first commercial fusion-power deals. While they offer optimism for fusion as a clean, abundant energy source, they also recall decades of “breakthrough” announcements that have yet to deliver practical, grid-ready power. The key question remains: how close is fusion to being not only proven, but scalable and commercially viable, and which projects worldwide are shaping its future?

Community Power Network Trial: Potential risks and market impact

Australia leads the world in rooftop solar, yet renters, apartment dwellers and low-income households remain excluded from many of the benefits. Ausgrid’s proposed Community Power Network trial seeks to address this gap by installing and operating shared solar and batteries, with returns redistributed to local customers. While the model could broaden access, it also challenges the long-standing separation between monopoly networks and contestable markets, raising questions about precedent, competitive neutrality, cross-subsidies, and the potential for market distortion. We take a look at the trial’s design, its domestic and international precedents, associated risks and considerations, and the broader implications for the energy market.

Competition a key to VPP development: ACCC report

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s most recent report on the electricity market provides good insights into the extent of emerging energy services such as virtual power plants (VPPs), electric vehicle tariffs and behavioural demand response programs. As highlighted by the focus in the ACCC’s report, retailers are actively engaging in innovation and new energy services, such as VPPs. Here we look at what the report found in relation to the emergence of VPPs, which are expected to play an important and growing role in the grid as more homes install solar with battery storage, the benefits that can accrue to customers, as well as potential areas for considerations to support this emerging new market.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.