Data Centres and Energy Demand – What’s Needed?

The growth in data centres brings with it increased energy demands and as a result the use of power has become the number one issue for their operators globally.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) electricity consumption from data centres, artificial intelligence (AI) and the cryptocurrency sector could double by 2026, with data centres being significant drivers of growth in electricity demand in many regions. They used an estimated 460 terawatt-hours (TWh) in 2022 and are projected to consume more than 1000 TWh by 2026 (a demand level roughly equivalent to the electricity consumption of Japan).

Australia is seen as a country that will continue to see growth in data centres and Morgan Stanley Research have taken a detailed look at both the anticipated growth in data centres in Australia and what it might mean for our grid. The expectation is the grid will be able to accommodate the energy demand from data centre growth until 2030, but it could become constrained in the 2030s as we see more coal plants exit the market unless there are efficiency gains or development of new generation. We take a closer look.

Growth

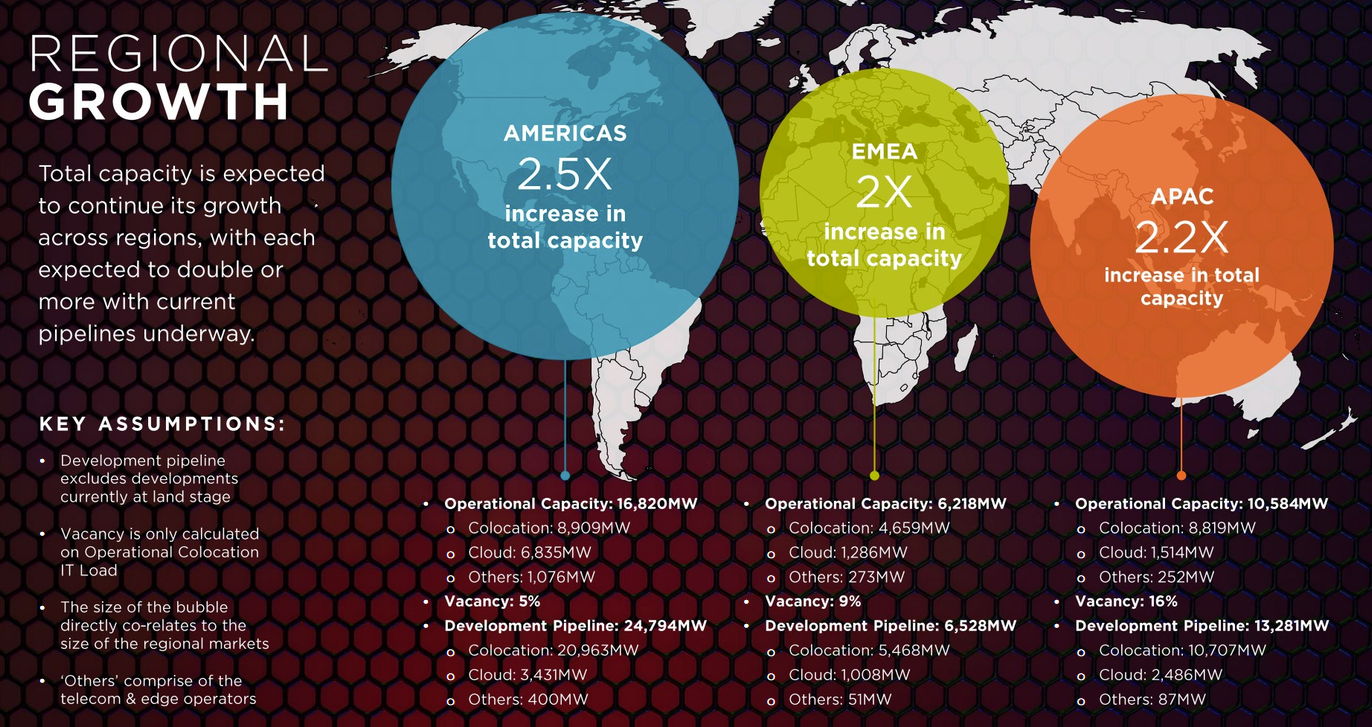

An estimated 4000 data centres (DCs) operate globally and Australia is in the top 5, locations with a similar capacity to London. Cushman & Wakefield, a global real estate commercial services company that tracks DC developments, reports there were DCs with 7.1 GW of total power requirements under development across 63 markets in 2023. Since then, this had grown to 12 GW for all DCs under development.

Source: Global Data Centre Market Development, Cushman & Wakefield, 2024

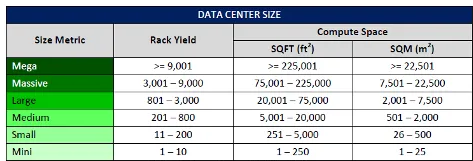

According to the Mega Data Centre Market Size & Share Analysis - Growth Trends & Forecasts (2023-2028) report analysis, the growth in the digital economy and the exponential rise in data consumption has seen strong growth in the development of “mega” data centres (see table below for size definition). The mega DC market, valued at USD 23.23 billion ($37 billion) in 2023, is projected to expand to USD 29.34 billion ($44 billion) by 2028, growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 4.78 per cent during the forecast period.

Last year, data centres saw substantial growth, driven by an increase in artificial intelligence and cloud computing. This increase in computing power has also expanded the cooling capacity needed to protect to protect it and adding strain on energy systems. As a result a potential limiting factor will be the availability and price of power. Given this expected growth in energy demand, data centre operators are now facing stricter regulations, and greater pressure to reduce their energy use, according to the Annual Global Data Center survey. In 2019 Singapore paused development of new data centre’s in response to their high energy consumption. This was to buy time for the government to conduct a review on how to grow the data centre industry in a more sustainable manner.

Singapore imports most of its electricity and because of its year-round high temperatures and humidity, a significant amount of energy is required to cool servers. Data centres are estimated to account for more than 7 per cent of the country’s electricity use now. The moratorium was lifted in 2022.

The Australian Situation

Morgan Stanley Research forecasts that most of the load growth in Australia is expected to emerge in New South Wales and Victoria.

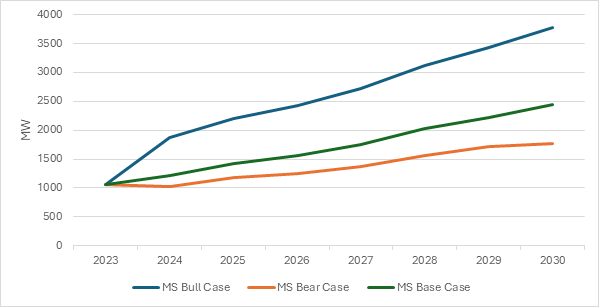

Overall, MS expects data centre energy demand to go from five per cent of total national electricity generation in Australia to eight per cent by 2030 - it could even reach as high as 15 per cent. In its base case, it expects data centre uninterruptible power supply requirements to increase from 1050 MW in 2024 to nearly 2500 MW in 2030, which is a 13 per cent increase (see figure 1.)

Figure 1 – Data Centre Forecast (Uninterruptible Power Supply)

Source: Morgan Stanley Research

MS’s most bullish scenario forecasts that data centres could require 3777 MW in 2030, a 20 per cent growth rate from 2023. Even its most pessimistic forecast sees an eight per cent growth in uninterruptible power supply requirements over the 2023-2030 period to 1762 MW (see above).

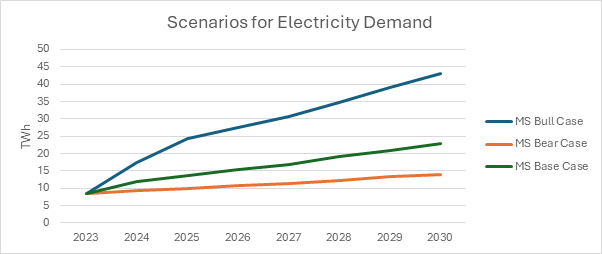

In terms of demand, MS forecasts that in its base case this could reach nearly 23 TWh in 2030, an 18 per cent increase from 2023. Under its bull case, electricity demand could be as high as 43 TWhs by 2030, with New South Wales accounting for 24.7 TWhs and Victoria a further 9.4 TWh. The National Electricity Market currently supplies about 200 TWhs to households and businesses annually.

Figure 2

Source: Morgan Stanley Research

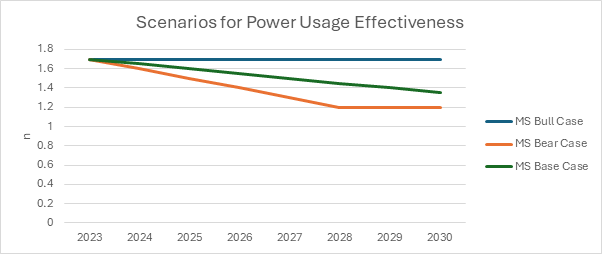

Power usage effectiveness (PUE), or power unit efficiency, is a ratio often used to assess data centre efficiency. This provides a ratio of total facility power to the IT equipment power, with the ideal being considered a PUE of 1. Globally, the average annual PUE reported in 2022 was 1.55.

MS expects the PUE under its bull case to remain at 1.7, the estimated current rating. Under its bear case this would fall to 1.2 and under the base case it would reach 1.35 by 2030 (see figure 3).

Figure 3

Source: Morgan Stanley Research

The Australian Federal Government is tightening energy efficiency regulations for data centres hosting federal agency workloads. These changes will mandate all data centre service providers to the government to achieve a five-star rating from the National Australian Built Environment Rating System (NABERS).

The Digital Transformation Agency (DTA) has established a new Data Centre Panel, which is designed to help promote sustainable practices across data centres and support the Federal Government’s move towards ‘net zero’.

The new Data Centre panel replaces a previous panel established in 2014 and includes a strengthened range of measures for data centre providers to identify, manage and reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. To be included on the panel, providers have to:

- meet the requirements of the Government’s ICT Sustainability Plan for data centres

- comply with emission thresholds under the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Act

- use accredited Greenpower from renewable sources

- have a 5-star NABERS rating or equivalent environmental rating

- target a PUE of less than 1.4

- have a plan to meet net zero emissions through innovation, planning and investment.

Based on average grid intensities based on renewable energy targets, MS estimates data centre Scope 2 emissions will reach 8 million tonnes, or around 2 per cent of Australia’s emissions and 40 per cent of our annual production of Australian Carbon Credit Units.

How do we meet the new demand?

Morgan Stanley has outlined three scenarios to meet the demand that will come from growth in data centres. The scenarios considered are:

- Fossil extension

- Renewable power purchase agreements (PPAs)

- Hourly-matched renewable power

Fossil Extension

Making use of existing but unused capacity is “potentially viable” but would also need more investment in capacity to manage peak demand periods (such as gas generators) and could significantly increase pressure on power prices and emissions.

Renewable PPAs

The report notes most data centres have renewable electricity procurement targets and suggests this would be the lowest cost approach for power development and power prices. MS modelled 82 per cent of non-matched renewable electricity to reflect the current Federal Government renewables target by 2030 as well as status quo business practice. That involves data centres entering PPAs with energy companies or developers to procure large-scale generation certificates (LGCs), “ideally from new projects to show additionality, but allowing the electricity market to solve for load shape, i.e., to match the actual power demand for the data centres”. In its report, Cushman and Wakefield reported last year it was not unusual to see data centres enter PPAs for 200-400MW, while Google signed a 600MW PPA for its Texas facilities.

Hourly matched renewables power

Considered a more aggressive renewable strategy, this involves data centres buying renewable energy in real time. Morgan Stanley modelled this approach using oversized wind generation for continuous load and oversized solar for daylight load with battery storage of around 6 hours per day to shift and cover supply and demand gaps.

Other options based on overseas experience include fuel cell technology and co-location with nuclear, although it notes this remains illegal in Australia. It also sees potential, with sufficient fiber, for global “follow the sun compute”, taking advantage of cheaper solar power. This would require companies to have, or to establish, data centres in multiple countries.

Related Analysis

Community Power Network Trial: Potential risks and market impact

Australia leads the world in rooftop solar, yet renters, apartment dwellers and low-income households remain excluded from many of the benefits. Ausgrid’s proposed Community Power Network trial seeks to address this gap by installing and operating shared solar and batteries, with returns redistributed to local customers. While the model could broaden access, it also challenges the long-standing separation between monopoly networks and contestable markets, raising questions about precedent, competitive neutrality, cross-subsidies, and the potential for market distortion. We take a look at the trial’s design, its domestic and international precedents, associated risks and considerations, and the broader implications for the energy market.

Competition a key to VPP development: ACCC report

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s most recent report on the electricity market provides good insights into the extent of emerging energy services such as virtual power plants (VPPs), electric vehicle tariffs and behavioural demand response programs. As highlighted by the focus in the ACCC’s report, retailers are actively engaging in innovation and new energy services, such as VPPs. Here we look at what the report found in relation to the emergence of VPPs, which are expected to play an important and growing role in the grid as more homes install solar with battery storage, the benefits that can accrue to customers, as well as potential areas for considerations to support this emerging new market.

Certificate schemes – good for governments, but what about customers?

Retailer certificate schemes have been growing in popularity in recent years as a policy mechanism to help deliver the energy transition. The report puts forward some recommendations on how to improve the efficiency of these schemes. It also includes a deeper dive into the Victorian Energy Upgrades program and South Australian Retailer Energy Productivity Scheme.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.