What's in the Carbon Capture and Storage pipeline?

Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) has the potential to be a key technological solution to the challenge of reducing carbon emissions. The Global CCS Institute has identified 38 large-scale CCS projects around the world, but has also highlighted that CCS has yet to make a significant contribution to reducing emissions. Currently, Australia has no completed large-scale CCS project, although there are numerous demonstration projects. A key issue for the technology internationally is that funding has progressively been scaled back with CCS not receiving the same level of support that most other clean energy technologies are receiving.

What is happening around the world?

The Paris Agreement is currently the bridge between today's policies and climate-neutrality before the end of the century. The mitigation targets which were volunteered by countries at the Paris Conference of Parties (COP) were aimed at meeting the long-term goal of keeping the increase in global average temperature to below 2°C above pre-industrial levels; with the additional aim of limiting the increase to 1.5°C and to undertake rapid reductions thereafter in accordance with the best available science[i]. More will need to done to curb emissions under these guiding principles, but it remains unclear what part CCS will play and whether it will be more actively pursued by many countries.

Of 38 large-scale projects internationally, the Global CCS Institute anticipates that more than 20 will be operational by the end of 2017[ii]. There have been two significant projects launched in 2016 – the Abu Dhabi CCS Project, with Phase 1 being the Emirates Steel Industries CCS Project, the world’s first large-scale application of CCS to iron and steel production, which was launched earlier this month [November]; and Japan’s Tomakomai CCS Demonstration Project in northern Japan, which started injecting CO2 injection in April 2016. The capture system captures emissions from a hydrogen production facility at Tomakomai port.

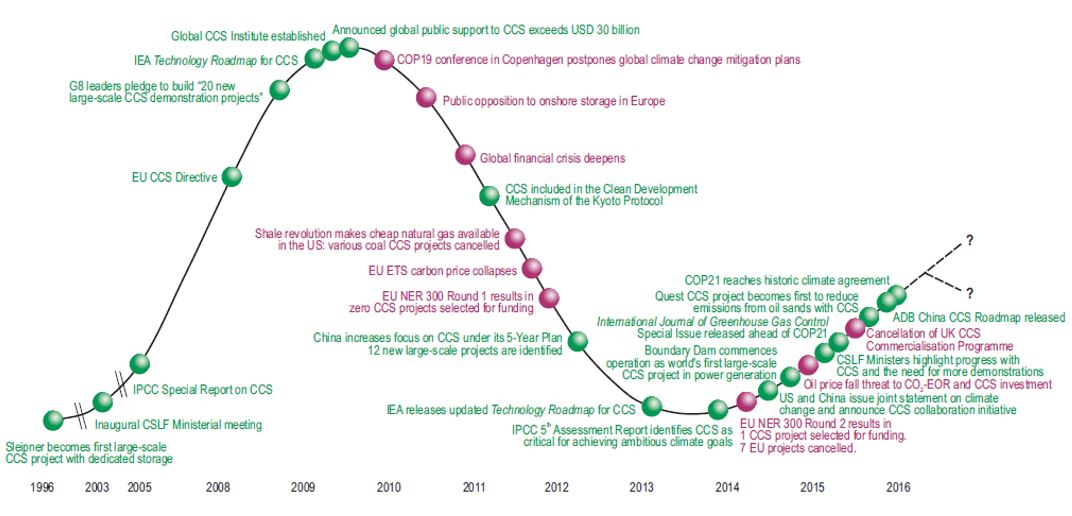

The map below shows some of the key CCS developments and milestones[iii].

Figure 1: Key CCS developments and milestones

Source: Global CCS Institute, 2016, “The Global Status of CCS 2016 – Summary Report”

There are several CCS demonstrated at scale projects in Australia although there is still no full utility-scale power plant operating commercially with CCS in the country[iv]. The Callide A coal plant in Queensland underwent a retrofit of oxyfuel technology and carbon capture equipment and has demonstrated successful operation but this was decommissioned in 2015/16 following a successful two-year demonstration of carbon capture technology[v]. The CO2CRC Otway project in Victoria has successfully injected CO2 into natural rock formations that trap the gas[vi]. There are several other pilot plants in operation and feasibility studies under way for the development of a co-ordinated transport and storage infrastructure.

It is encouraging to see some large scale demonstration projects but there still needs to be a lot more work done for CCS to have a significant impact on emission reduction. Currently CCS deployment has not made a significant impact to reduce emissions around the world.

Policy support fluctuates

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) the world would need to capture and store almost 4,000 million tonnes per annum (Mtpa) of CO2 in 2040 to meet a 2°C scenario. Currently carbon capture capacity for projects in operation or under construction sit at approximately 40 Mtpa. This highlights the need for more work so that CCS can make significant headway over the next years. CCS policy and political support over time has fluctuated, as can be seen in figure 2, with CCS not receiving the equal support as most other clean energy technologies around the world[vii].

Figure 2: CCS policy and political support over time

Source: International Energy Agency, 2016, “20 Years of Carbon Capture and Storage - Accelerating Future Deployment”

Although there is cause for optimism much of the momentum for CCS was lost when governments around the world continued to grapple with the global financial crisis. Between 2010 and 2016 there were more than 20 advanced large scale CCS projects cancelled and the announced funding commitments were either scaled back or withdrawn across Europe, the United States and Australia.

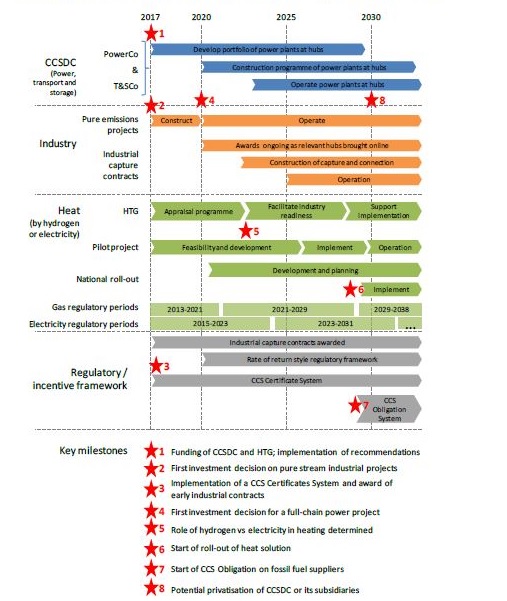

The United Kingdom’s CCS Commercialisation Programme was dropped in late 2015 while in the final stages of project selection and just days before COP21, which resulted in the cancellation of what were considered to be two highly prospective and important projects by CCS – Peterhead and White Rose. The Peterhead CCS project was the only advanced project proposing to apply CCS to gas-fired power generation, and White Rose would have been the first demonstration of oxy-fuel capture technology at scale.

Subsequently, a report from a Parliamentary inquiry set up in the wake of the cancellation argued the case for CCS and associated infrastructure in the UK and for its development now. It said electricity is the key facilitating sector for CCS[viii]. “Only electricity provides a large-scale, creditworthy route to financing the early CCS infrastructure the nation needs at its strategic industrial hubs”. In his letter to the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, the Chairman of the Parliamentary Advisory Group on CCS, Ron Oxburgh wrote that he had been surprised at “the absolutely central role which CCS has to play across the UK economy if we are to deliver the emissions reductions to which we are committed at the lowest possible cost to the UK consumer and taxpayer”[ix].

- The report recommended, amongst other things: Establish a CCS delivery company

- A system of economic regulation for CCS in the UK

- Incentive industrial CCS through industrial capture contracts to be funded by government

- Establishment of a CCS obligation system.

Figure 3 Milestones for development of CCS in the UK

Source: Parliamentary Advisory Group on Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), 2016, “Lowest Cost Decarbonistation for the UK: The Critical Role of CCS - Report to the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy from the Parliamentary Advisory Group on Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS)”.

In Australia, the CCS Flagships programme was $1.9 billion in 2009 according to the IEA, which has progressively been scaled back. In the 2014-15 Budget, the Federal Government reduced funding by $500 million over three years[x].

Despite scaling back funding, the Australian Government confirmed funding of over $125 million in its May 2014 Budget to allow the South West hub and CarbonNet projects to complete their stage gated commitments. In August 2016, the Australian Government announced grants of $23.7 million to seven applicants under the Carbon Capture and Storage Research Development and Demonstration Fund[xi]. The seven projects selected include both industry and research institution-led projects. These will further add to Australia’s knowledge and successful implementation of large scale CCS projects in Australia[xii].

There has also been support on a state level with the New South Wales (NSW) Government announcing that applications are open for AU$10 million of competitive grants for research into low-emissions coal technologies, including CCS[xiii]. In Victoria the CarbonNet Project is managed by the Victorian Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources which is investigating the potential for establishing a world class, large-scale carbon capture and storage network[xiv].

[i] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2015, “Historic Paris Agreement on Climate Change”, <<http://newsroom.unfccc.int/unfccc-newsroom/finale-cop21/ >>

[ii] Global CCS Institute, 2016, “The Global Status of CCS 2016 – Summary Report”

[iii] ibid

[iv] ibid

[v] CS Energy website, << http://www.csenergy.com.au/content-(19)-callide.htm >>

[vi] http://www.co2crc.com.au/research/ausprojects.html

[vii] International Energy Agency, 2016, “20 Years of Carbon Capture and Storage - Accelerating Future Deployment”

[viii] Parliamentary Advisory Group on Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), 2016, “Lowest Cost Decarbonistation for the UK: The Critical Role of CCS - Report to the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy from the Parliamentary Advisory Group on Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS)”

[ix] Ibid

[x] Australian Federal Budget 2014-15

[xi] Australian Government, 2016, “$23.7 million for carbon capture and storage”, << http://www.minister.industry.gov.au/ministers/canavan/media-releases/237-million-carbon-capture-and-storage >>

[xii] ibid

[xiii] Global CCS Institute website, 2016, << https://www.globalccsinstitute.com/news/institute-updates/latest-ccs-funding-update >>

[xiv] ibid

Related Analysis

Certificate schemes – good for governments, but what about customers?

Retailer certificate schemes have been growing in popularity in recent years as a policy mechanism to help deliver the energy transition. The report puts forward some recommendations on how to improve the efficiency of these schemes. It also includes a deeper dive into the Victorian Energy Upgrades program and South Australian Retailer Energy Productivity Scheme.

2025 Election: A tale of two campaigns

The election has been called and the campaigning has started in earnest. With both major parties proposing a markedly different path to deliver the energy transition and to reach net zero, we take a look at what sits beneath the big headlines and analyse how the current Labor Government is tracking towards its targets, and how a potential future Coalition Government might deliver on their commitments.

The return of Trump: What does it mean for Australia’s 2035 target?

Donald Trump’s decisive election win has given him a mandate to enact sweeping policy changes, including in the energy sector, potentially altering the US’s energy landscape. His proposals, which include halting offshore wind projects, withdrawing the US from the Paris Climate Agreement and dismantling the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), could have a knock-on effect across the globe, as countries try to navigate a path towards net zero. So, what are his policies, and what do they mean for Australia’s own emission reduction targets? We take a look.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.