Australia will soon have a Net Zero Plan – what can we expect?

Like most of the world, Australia has pledged to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 under the Paris Agreement. To help the nation get there, the Federal Government has promised to develop a Net Zero Plan by the end of the year, which will involve integrating six sector plans.

But with most sectoral decarbonisation policies focused only up until 2030, some unknowns are emerging about what this Plan might look like and how it intends to merge the sector pathways to promote an orderly and efficient economy-wide transition.

The Net Zero Plan in a nutshell

The Federal Government has committed to developing six sector plans:

- Electricity and energy (first round of consultation complete)

- Agriculture and land (first round of consultation complete)

- Transport and infrastructure

- Industry and waste

- Resources

- Built environment

Different government departments are responsible for leading each sector plan, with there likely to be two rounds of stakeholder consultation to sort through the main issues. Once final, these six sector plans will then be merged into a final Net Zero Plan, which the Federal Government intends to publish by the end of this year. The Climate Change Authority (CCA) will also provide independent advice to the Government as part of its Sectoral Pathways Review.

It is expected that the Net Zero Plan will take a target-aligned trajectory, meaning it will follow the Government’s 43 per cent target by 2030, and potentially any 2035 target if announced in time.

The consultations undertaken thus far have not put forward any policy surprises, and instead just summarised the policy actions already underway in that sector. This has created some curiosity about how exactly the sector plans will come together to add to the delivery of the net-zero target.

Existing sector abatement policies

The Federal Government currently has three core policies to drive abatement:

- Capacity Investment Scheme (targeted at electricity emissions)

- Safeguard Mechanism Reforms (targeted at stationary energy and industrial emissions)

- New Vehicle Efficiency Standard (targeted at transport emissions)

These three policies are tailored towards meeting the Federal Government’s 43 per cent interim emissions reduction target by 2030, with their projected emissions impact shown below.

Figure 1: Emissions projections by sector (excluding LULUCF) under “with additional measures” scenario (MtCO2-e)

| Sector | 2005 Emissions | 2030 Emissions | Difference (+/-) |

| Electricity | 197 | 60 | -137 |

| Stationary energy | 82 | 96 | +14 |

| Transport | 82 | 94 | +12 |

| Fugitives | 43 | 46 | +3 |

| Agriculture | 86 | 80 | -6 |

| Industrial | 30 | 25 | -5 |

| Waste | 16 | 13 | -3 |

| Total | 535 | 415 | -120 |

Source: Federal Government’s Emissions Projections 2023, p20-21.

As can be seen, it is expected electricity will play such an oversized role in contributing to Australia’s 2030 emissions target that it must cover inaction across all other sectors. This scenario rests on the assumption that Australia’s electricity sector reaches 82 per cent renewable energy by 2030, in line with the Federal Government’s ambitious target.

It is not currently clear how the Net Zero Plan will, if at all, consider sensitivity analysis (e.g. what happens if electricity undershoots on this target). The CCA’s 2023 Annual Progress Report found that undershooting is a possibility and the impact would be material: “every percentage point we fall short of achieving 82 per cent renewables equates to roughly 2 Mt C02-e that needs to be reduced elsewhere in the economy”.[i]

It may simply be the case that modelling different scenarios between now and 2030 is of low value, due to the reality that sectors other than electricity are not going to do much. There is also the plausible explanation that the Federal Government has set up an enduring policy framework to drive decarbonisation up until 2030, and the work ahead is now mainly an implementation task.

The path forward after 2030 is no yellow brick road

The biggest challenge then lays in how the Net Zero Plan will map a decarbonisation trajectory for each sector and ultimately Australia’s economy after 2030. So far, only electricity has somewhat of a transition roadmap post-2030 through the Australian Energy Market Operator’s Integrated System Plan and the scheduled closure of coal-fired power stations representing checkpoints for when new generation must be online. Even then, the potential for an extension to Eraring’s retirement by four years shows that getting enough clean generation online in time is no easy task.

As for the other sectors, the Government has deliberately avoided mapping out decarbonisation beyond 2030:

- For The New Vehicle Efficiency Standard: “it is not appropriate to set the headline limits for vehicles for 2030 and beyond now because the vehicle market and technology that will be available in 2030 and beyond is uncertain”.[ii]

- For the Safeguard Mechanism: “post-2030 decline rates would be set in predictable five-year blocks, after updates to Australia’s Nationally Determined Contribution under the Paris Agreement”.[iii]

- For sectors like agriculture or aviation where there is no carbon policy, the hope is technologies will emerge in the future to drive abatement.

There is not much visibility over how the Net Zero Plan intends to grapple with this challenge. The current expectation is government departments will come together to undertake some type of modelling exercise that puts each sector on a trajectory to net-zero, and then integrates these sector plans into one economy-wide Net Zero Plan.

This expectation triggers obvious questions about what assumptions will be used to forecast each sector’s decarbonisation trajectory, what evidence will guide the selection of those assumptions, and the level of specificity. For example, will the Net Zero Plan:

- Provide emissions or technology targets – targets can spur progress, but also lock-in inefficient abatement and investment, increasing the cost of the transition. It seems this has been ruled out for now, with the Agriculture Sector Plan Discussion Paper stating “there is no expectation that there will be sector-specific emissions reduction targets … [but] it may be useful to consider goals or indicators”.

- Implement de facto carbon pricing and offset allocation – the net in net-zero exists to allow for offsetting a small volume of emissions that are either too expensive and/or where no viable abatement option exists. Every sector will probably make a claim for offsets and without a carbon price, it will be difficult to determine their allocation efficiently.

- Even the electricity sector, which has the clearest technology path for decarbonisation, is still unlikely to reach absolute zero emissions. AEMO has projected the total renewable generation share of the National Electricity Market to be around 96 per cent by 2040, and 98 per cent by 2050, with offset gas-powered generation being used for the remaining percentages.

- Identify sector pathway sensitivities – this was referenced earlier in the context of electricity but might have bigger implications for other sectors. For example, what happens if future abatement technologies for hard-to-abate sectors like aviation or agriculture take longer than expected to be economically viable, or are less effective than anticipated?

Stakeholders will want transparency of this process and to understand what level of detail to expect as it will have impacts on investment and planning across each sector. For electricity, the biggest “integration question” relates to the scale and pace at which other sectors electrify. This is because electrification will influence future peak electricity demand and consumption, and consequently the volume and timing of electricity generation and infrastructure needed to be built.

Electrification and sector plan integration

Electrification is expected to play a significant role in decarbonising transport (i.e. replacing combustion vehicles with electric vehicles) and some stationary energy activities (e.g. replacing gas appliances used for residential heating with electric appliances). The uptake of electrification will significantly increase total electricity consumption as well as requiring forward system planning to manage changes to maximum and minimum electricity demand.

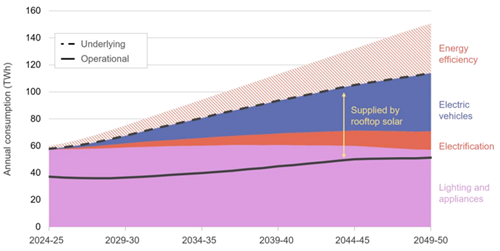

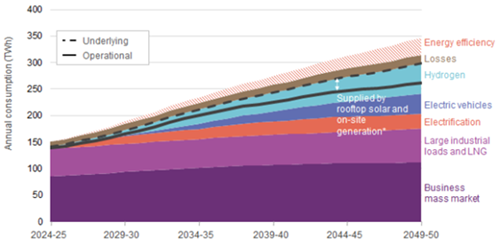

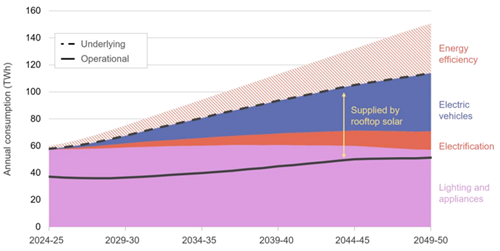

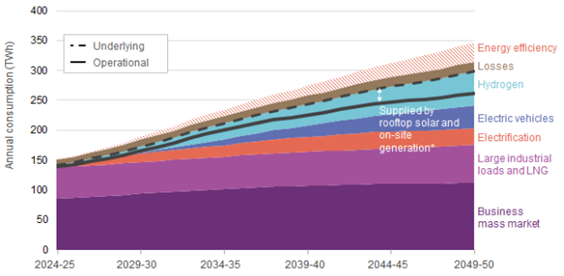

The two graphs below show the growth in electricity consumption up until 2050 under AEMO’s Step Change scenario in its 2024 Draft Integrated System Plan.

Figure 2: Residential electricity consumption, NEM (TWh, 2024-25 to 2049-50, Step Change)

Figure 3: Business and industry electricity consumption, NEM (2024-25 to 2049-50, Step Change)

Source: AEMO Draft 2024 Integrated System Plan, p26-27.

One part of the equation to meeting this increased consumption is building more renewable generation. The other part, illustrated best in Figure 2, involves the orchestration of Consumer Energy Resources (CER) technologies, especially rooftop solar, to cover virtually all the consumption from residential electric vehicle charging and electric appliance usage.

But this is not as simple as rolling out enough rooftop solar to meet demand and then ‘plugging customers in’. It also requires a range of regulatory and technical reforms to be implemented well ahead of time. These reforms are about managing both peak demand (making sure customers are not all charging their electric vehicles at the same time of the day. If this were to happen, the electricity grid would need to build significant capacity to meet peak demand, increasing costs of the transition), as well as minimum demand (also ensuring enough grid-connected electricity generation stays online to provide essential system security services). There are then further complications relating to voltage operational limits that must be resolved to ensure CER technologies are not damaged or unsafe to use.

Electrification then is a good example of how the decarbonisation pathways of each sector are intimately tied to each other and why there needs to be greater visibility over how integration will occur. If that is to form part of the second round of stakeholder consultation it will be warmly welcomed, but if not, then meaningful engagement with separate sector plans will become a confusing and difficult exercise.

Conclusion

The Net Zero Plan is something Australia should have so its international partners, investors, businesses, and community can see how our policy actions align with the Paris Agreement goals. At the same time, its current development is highlighting some of the policy knots that come with taking a sector-by-sector approach to carbon abatement.

Without reference to an economy-wide carbon price, a sector-by-sector approach makes it difficult to ensure abatement occurs efficiently, and this increases the need for the sectoral integration aspects to be visible. It is still early days yet, but it is important we get this right.

[i] Climate Change Authority, ‘2023 Annual Progress Report’, October 2023, p6.

[ii] Australian Government, ‘New Vehicle Efficiency Standard: Explanatory Memorandum’, p22, https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/legislation/ems/r7182_ems_1ca0d0ea-1fa8-4406-8c04-9a58cb1b5d5a/upload_pdf/JC012584.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf.

[iii] Department of Climate Change, Energy, Environment, and Water, ‘Safeguard Mechanism Reforms’, May 2023, p2, https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/safeguard-mechanism-reforms-factsheet-2023.pdf.

Related Analysis

Australia's Solar Waste: A Growing Problem

Australia has long been a global leader in the adoption of solar energy, with one of the highest per capita rates of rooftop solar installations worldwide. Solar power has become a cornerstone in the nation's commitment to sustainability, contributing significantly to reducing its carbon footprint and reliance on fossil fuels. However, as solar panels reach the end of their lifespan, the issue of solar panel waste is rapidly emerging as a significant environmental challenge that could escalate in the coming decades. We take a closer look.

Australia’s net zero plan is looking a lot like an electricity-only plan

The past three years have seen a stronger commitment to encouraging economy-wide decarbonisation, as seen through reforms to the Safeguard Mechanism and new policies like the New Vehicle Efficiency Standard and Future Made in Australia. But the release of two emissions reduction progress reports paints a sobering reality – no sector other than electricity is doing anything to help Australia meet its 2030 target. Is this leading to the proverbial “all eggs in one basket”? Or is electricity decarbonisation really the only viable pathway to 43 per cent by 2030? We take a closer look.

Frontier Economics and the cost of the transition: How does it stack up?

Nearly two weeks ago, headlines revealed Australia’s energy transition would be more expensive than previously estimated. This news stemmed from modelling by Frontier Economics, which highlighted long-term costs beyond the commonly cited net present value figure of $122 billion in capital cost, as outlined in the Australian Energy Market Operator’s (AEMO) 2024 Integrated System Plan (ISP). We took a closer look.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.