Australia’s workforce shortage: A potential obstacle on the road to net zero

Australia is no stranger to ambitious climate policies. In 2022, the Labor party campaigned on transitioning Australia’s grid to 82 per cent renewable energy by 2030, which even Chris Bowen, the Federal Energy Minister, admitted was ambitious during his most recent National Press Club address.

Earlier this year, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese unveiled the Future Made in Australia agenda, a project that aims to “create new jobs and opportunities for every part of our country by maximising the economic and industrial benefits of the move to net zero and securing Australia’s place in a changing global economic and strategic landscape”[i]. While the Future Made in Australia project has unveiled a raft of potential economic opportunities for Australia, it has also highlighted a problem that will continue to grow as the transition continues: a lack of skilled workers.

The current outlook

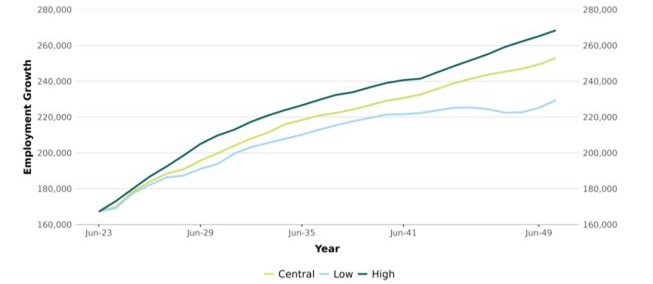

Jobs and Skills Australia (JSA), an independent government group that provides advice on current, emerging and future workforce, skills, and training needs, estimates Australia will require “two million workers in building and engineering trades by 2050 to prepare Australia’s energy grid and industrial base for net zero,”[ii] including 53,000 to 84,000 more electricians (depending on the different policy approaches to electrifying the National Electricity Market (NEM) and reaching our renewable energy goals).

Figure 1: Demand for Electricians by 2050

Source: The Clean Energy Generation report, Jobs and Skills Australia, 2023

The July 2024 Workforce Planning Report, released by the Powering Skills Organisation (PSO), reports the energy sector having around 241,600 workers, accounting for around two per cent of the Australian workforce. This sector is split into four categories:

1. Electrical services – workers engaged in the installation, augmentation, and repair of electrical wiring or fittings in buildings and construction projects (like mining and manufacturing).

2. Electricity supply – overseeing the generation, transmission, and distribution of electricity.

3. Air Conditioning and Heating Services – the installation of heating, refrigeration, or air conditioning equipment.

4. Gas Supply – Workers whose primary task is the distribution of gas

The energy sector is central to Australia reaching its net zero emission targets, and having a strong, skilled workforce is crucial to this. Modelling by PSO suggests the additional critical energy sector workers required to deliver the transition alone could be up to 17,400 by 2030, rising to 37,600 by 2050. As mentioned above, electricians are expected to be in high demand.

Labour supply for electricians is forecast to grow only slowly, due to relatively flat tertiary completions and a relatively older current workforce. This means there is likely to be a growing supply gap unless we see a significant increase in electrician completions in Vocational Education and Training (VET) courses, with these completions also converting into actual employment. Modelling by JSA found Australia will likely need 85,000 more electricians by 2050, with 32,000 more needed by 2030. PSO’s 2024 Workforce Plan suggests the energy sector is “projected to face shortfalls of over 14,000 electricians by 2030, growing to nearly 34,000 by 2050”.

Figure 2: Projected shortfalls of electricians employed in the energy sector, 2030-2050.

Source: Powering Skills Organisations, Workforce Plan 2024

To help mitigate this shortfall, PSO suggests Australia needs an estimated “20,500 apprentice electricians to commence annually from 2024-2030 to align with the forecast demand, which is 40 per cent higher than the yearly average from 2015-2023” (a comparable seven-year period).

This increase would help Australia meet the needs of the net zero transformation as well as keeping the broader economy functioning at the same time.

Additionally, nearly all building and engineering trades critical to the construction (and maintenance) phases of renewable electricity generation are also likely to experience supply gaps.[iii] Significant gaps in architectural, building and surveying technicians, metal fitters and machinists, structural steel and welding trade workers as well as chemical, gas, petroleum and power generation plant operators will emerge, further adding strain to the speed in which Australia can safely transition to net zero.

The international problem

Australia is not alone in pursuing net zero emissions. Governments around the world are working to meet their own energy needs, achieve decarbonisation commitments, and develop lucrative clean energy export opportunities. To fulfil these ambitions and goals, governments are relying heavily on skilled migration to support their transition, leading to an increase in competition for migrants with the required skills, qualifications and experience.

The government is aware of this issue. Last September, Home Affairs Minister Clare O’Neil said “for the first time in our history, Australia is not the destination of choice for many of the world’s skilled migrants. The best and the brightest minds on the move are instead looking to live in countries like Canada, Germany, and the UK.” A 2021 analysis by the Boston Consulting Group affirmed this statement, ranking Australia as the “third most appealing destination to migrant workers behind Canada and the US”, with it being less attractive to highly educated respondents. Positively, Australia remains the most appealing country for those migrating from the Asia-Pacific region.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates the global energy workforce is at around 65 million, with just over 50 per cent employed in clean energy-related activities. The largest and fastest growing clean energy workforce is in China, at over 10 million. By 2030, the IEA predicts the workforce to increase to 80 million, an increase of around 14 million.[iv]

Figure 3: Energy employment in fossil fuel and clean energy sectors by region, 2019, in thousands of employees.

Source: World Energy Employment 2022, International Energy Agency.

Recognition of foreign qualifications

Whilst efforts to skill, upskill and reskill the domestic population will drive the net zero transformation, it will also be heavily reliant on effective migration settings to assist in addressing existing and anticipated skills gaps and support the growth of the clean energy workforce.

The permanent skilled migration program requires most applicants to undergo an assessment of their skills, qualifications and work experience to ensure they meet the standards needed for employment in Australia. These assessments vary by occupation and country, ranging from straightforward document verification to more complex assessment procedures. A significant proportion of clean energy workers in Australia received their highest qualification overseas. However, having these qualifications recognised for the purposes of gaining employment in Australia is not always a simple process.

For example, Australia is a full signatory to the 1989 Washington Accord, which is an agreement between numerous countries for accreditation or recognition of tertiary level engineering qualifications. Under the accord, qualifications accredited or recognised by other signatories are recognised by each signatory as being substantially recognised qualifications within its own jurisdiction. There are 23 full signatories and six provisional signatories to the accord, meaning that many engineering professionals receive expedited recognition when migrating to Australia.

For other clean energy-related occupations, like electricians, skilled migrants are required to undergo a skills assessment, regardless of where their qualifications were obtained, with the exception of New Zealanders whose qualifications are recognised under the Trans-Tasman Mutual Recognition Act 1997.

The 2023 Migration Review found Australia’s current migration program is unfit for purpose and fails to attract the skilled workers we need.[v] Due to Australia’s strict skills assessments, some migrants fail to meet onshore licencing requirements even after passing a pre-migration skills assessment, leaving workers in ‘labour market limbo’[vi]. While migration alone will not address the challenges of transitioning to a clean energy economy, a well-designed and fit for purposed skilled migration program can be part of the solution, filling gaps in the pool of domestic workers.

Challenges in overcoming shortfall

By 2030, Australia is expected to require an additional 85,000 workers to support the construction, operation, and maintenance of the renewable energy infrastructure. The Australian Industry Energy Transitions Initiative Report, published in February 2023, found at least 51 per cent of those 85,000 workers needed by 2030 are in national shortage occupations, such as electricians, engineers and plant operators. 39 per cent of the additional workers (33,100) are in higher skilled operations, requiring formal education and training at TAFE or university which generally takes three to four years to complete. Because of the time it takes for students to become qualified, it is critical action be taken as soon as possible to ensure Australia is able to grow its workforce without delay.

Growth of the energy trades workforce is also dependent on rapid growth of capable VET trainers. JSA data shows VET trainers have been in shortage for the past two years, with a shortage of VET trainers specialising in energy having been a long-term issue.[vii] As a result of these trainer shortages, training providers are reportedly at maximum capacity and have been unable to accept the full cohort of electrical apprentices across Australia. Anecdotal feedback from PSO suggests “while forecast energy apprentice numbers are increasing, they will not be reached because of a shortage of trainers.”[viii]

This is a concern as most clean energy technology skills or training options will be gained through the VET system via renewable energy units. An example of this if the offshore wind sector. Many of the skills required to be an offshore wind electrician are general electrical trade skills which can be gained across existing industries rather than the wind sector specifically. Specific competencies and skillsets related to offshore wind then require additional training to transition into the sector. While new trade qualifications targeted at emerging renewable sectors will appear, the vast majority of the clean energy skills gap could be filled through the model of additional skillsets or ‘top up electives’ that build on existing qualification pathways, which is why it is crucial for the VET system to be an attractive option for potential new trainers.

Conclusion

It is critical that an effective whole-of-government approach to be taken as we transition to net zero. There are currently a raft of government strategies addressing how Australia should transition the energy sector, with all of them impacting the workforce. For these to be achieved, solutions must be found on how Australia will meet its workforce shortages both now and into the future. Every major economy in the world is working towards transitioning their energy grid, resulting in a global shortage of skilled workers worldwide. If we are to rely on international workers, then changes must be made to Australia’s recognition of international qualifications to ensure we are able to expand our workforce as quickly as possible. If we are not to rely on the global workforce, then measures will need to be taken to address the gaps within the domestic workforce, including expanding education and training to increase the potential pool of future workers. If Australia is not to take action to mitigate this workforce shortage, then the challenge of transitioning becomes a far greater task.

[i] https://budget.gov.au/content/03-future-made.htm

[ii] https://www.jobsandskills.gov.au/publications/the-clean-energy-generation

[iii]https://poweringskills.com.au/wpcontent/uploads/2024/07/Workforce_Plan_Report_2024_Final_15July2024.pdf

[iv] Net Zero by 2050 – Analysis - IEA

[v] https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/review-migration-system-final-report.pdf

[vi] https://cedakenticomedia.blob.core.windows.net/cedamediatest/kentico/media/attachments/powering-the-transition-ceda.pdf

[vii] https://www.jobsandskills.gov.au/news/2023-skills-priority-list-released-0

[viii]https://poweringskills.com.au/wpcontent/uploads/2024/07/Workforce_Plan_Report_2024_Final_15July2024.pdf

Related Analysis

The GHG Protocol: make or break for green data centres?

In the past few months, data centres have received significant attention as potential beehives for renewable investment and an antidote to the much-publicised tenor gap. But some recent changes being discussed globally could complicate how businesses such as data centres purchase their electricity. If not navigated carefully, these changes could make the vision of 100 per cent renewable powered data centres a distant fantasy rather than a reality. Let’s take a closer look.

What does the Queensland Energy Roadmap mean for the 2026 ISP?

The Queensland Government recently unveiled its new Energy Roadmap for the state. The new Roadmap reshapes the pace and scale of the state’s energy transition by opting to retain the state’s existing coal assets in Queensland’s generation mix for longer. Somewhat coincidentally, the AEMC has started consultation on the “treatment of jurisdictional policies” like the Queensland Energy Roadmap in AEMO’s Integrated System Plan (“ISP’) as part of its broader Statutory Review of the ISP. So what does Queensland’s new Roadmap mean for AEMO’s signature whole-of-system electricity plan? We take a closer look.

Nuclear Fusion Deals – Based on reality or a dream?

Last week, Italian energy company ENI announced a $1 billion (USD) purchase of electricity from U.S.-based Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS), described as the world’s leading commercial fusion energy company and backed by Bill Gates’ Breakthrough Energy Ventures. CFS plans to start building its Arc facility in 2027–28, targeting electricity supply to the grid in the early 2030s. Earlier this year, Google also signed a commercial agreement with CFS. These are considered the world’s first commercial fusion-power deals. While they offer optimism for fusion as a clean, abundant energy source, they also recall decades of “breakthrough” announcements that have yet to deliver practical, grid-ready power. The key question remains: how close is fusion to being not only proven, but scalable and commercially viable, and which projects worldwide are shaping its future?

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.