Wholesale Demand Response Mechanism: Poised to go ahead

Today the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) published its draft determination on a Wholesale Demand Response Mechanism (DRM). The concept first emerged in the AEMC’s ground-breaking Power of Choice (PoC) Review in 2011, and was subsequently developed, assessed, rejected, re-emerged and is now on the verge of being imposed on the market. We take a look at what all the fuss is about that has kept it in, and out, and back, in play for so long.

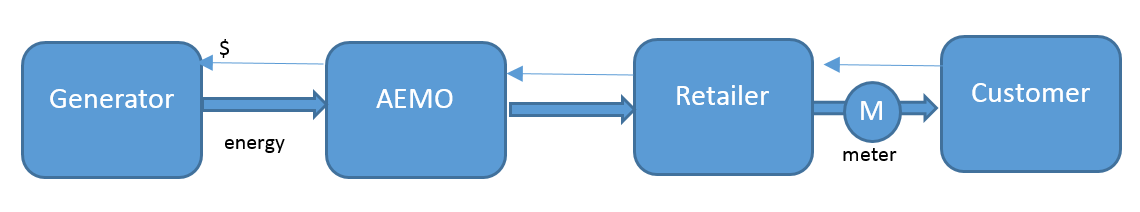

How Demand-Response operates now

Demand Response (DR) is an excellent resource for power systems such as those in Southern Australia subject to extreme “needle-peak” heat waves and variable supply sources. It can provide capacity at very low capital cost compared to generation, although it usually has a very high operating cost and complex managerial challenges.

In the NEM, each customer has one “Financially Responsible Market Participant”, which we call a retailer. They take on all the market settlement responsibilities for that customer.

In this construct, the financial benefit of demand-response is simple and obvious. If the customer reduces consumption, the retailer will have to pay less to AEMO, but will also receive less from the customer. Whenever the wholesale spot price exceeds the customer’s retail tariff, there is a benefit to the retailer in encouraging the customer to consume less. Of course, the customer would presumably be doing something useful with the electricity, so it would need to be a very high margin (i.e. a time of high spot price) to compensate for the inconvenience.

Importantly, this incentive is unaffected by the Retailer’s broader business. Irrespective of whether the Retailer has contracts with, or directly owns a generator, the retailer will improve its financial position by activating the DR. Even if the retailer already has a “long” position, i.e. is receiving more from its generators and contracts than it is paying out for its customers, activating DR from one of its customers will make it even longer. This means, at the margin, when prices are high, exercising DR is always beneficial for the retailer no matter what’s going on in the rest of its business.

So retailers look to exploit such opportunities with their customers, and, in order to compensate for the inconvenience, provide various incentives to the customers who do respond. Sometimes retailers engage a third-party expert to investigate and setup ways to maximize the response from customers. This we call a “Demand Response Service Provider” (DRSP). They will earn a fee, but they won’t be involved in the actual market settlement.

Customers, being rightly focused on matters other than electricity, don’t always respond in exactly the way anticipated. Unlike generators, customers are not slaves. And, if the DR turns out to be less than expected it remains a matter for discussion and resolution between the retailer and the customer – no other party is affected.

So what’s the problem?

The NEM is often criticized for failing to fully exploit DR potential. But this claim can never be fully quantified, because:

- DR is non-scheduled. This means, unlike generators, there is no clear data on how much load is actually available for response. Attempts to capture it centrally[i] notoriously under-report it, giving false impressions.

- We don’t know what the efficient level of DR really is. Economists grew up learning about symmetrical supply-demand curves, however DR is quite disruptive for many customers, and so we should not be disappointed by their non-participation.

Nevertheless, critics of the current arrangements remain unconvinced that retailers are fully exploiting their customers’ DR capabilities. They argue:

- Due to lack of experience or cultural inertia, retailers are failing to uncover opportunities in their customer base that could actually benefit themselves. In response, we would say the forces of retail competition should resolve this.

- Vertically integrated retailers see DR as a competitor to their generation assets. Yet, as discussed above, exercising DR on a customer will always improve a retailers’ total financial position, unless the customer is so large that its activation will actually cause the NEM-wide price to drop. Very few customers are of such a size, and even in that case, the forces of competition would soon see them move to another retailer.

There was also another, more valid, concern expressed at the PoC review that if the DR requires a significant set up, it may not be worth it if the retailer’s customer contract is short. For that reason the AEC proposed a rule change to install a DR register to allow DR arrangements to survive a change of retailer. The draft determination has instead chosen a less minimalist path.

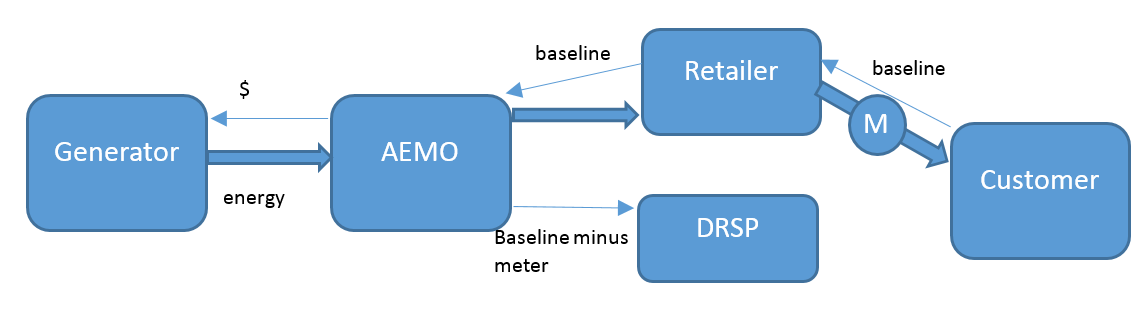

The DRM

Those who consider the retailer to be an obstacle have continued to advocate a scheme, adopted from the US, where DRSPs activate DR during high prices and receive the benefit of doing so from AEMO. Meanwhile retailers have to keep paying AEMO as if the DR never happened.

The following diagram represents the financial flows with some indicative amounts.

Source: AEMC

Source: AEMC

This proposal has proven highly controversial to the industry for two main reasons:

- The introduction of a second financially responsible market participant in the customer-market relationship is problematic for retailers, both through confusing their relationship with customers, and through incompatibility with existing billing systems. Retailer systems would have to undergo expensive changes for others to gain access to their own customers!

- The design, by definition, requires the measurement of an absence of consumption, and forming a view on the counter-factual: what would the customer have done in another circumstance? This is very difficult to do with confidence and the risks of errors falls on the retailer. A recent Energy Insider dealt with this in detail[ii].

When the DRM was studied from 2012-2015, it was ultimately rejected for the above reasons. However it never quite died. In 2017 the Finkel Review recommended[iii] its re-investigation, followed by the AEMC Reliability Frameworks Review[iv] and ACCC Retail Electricity Price Investigation of 2018[v].

The scene was set and a coalition of parties re-submitted the proposal in late 2018 as a rule change[vi]. These parties have kept the pressure on, with media coverage on an otherwise complex and arcane matter. Media stories have tended to present a “David vs Goliath” narrative[vii].

The Draft Determination

Today’s decision went against the industry’s preference in recommending that the DRM progress. The AEMC undertook consultation, including a technical working group that explored three rule changes at once. Importantly it has proposed some significant implementation features. These are:

- That the DRM is available, at least initially, to large customers only. This is sensible, as large customers were always the DM resource envisaged by the DRM, and there are complex consumer protection issues combined with the most difficult baselining issues and system costs with small customers.

- A detailed baselining methodology to be developed and consulted by AEMO.

- That customers using the DRM must be scheduled, similar to how large generators are controlled. The NEM has always allowed customers to elect to be sent dispatch targets by AEMO, however as it is voluntary, and involves some private inconvenience, this has not been used. There is however benefit to the broader market, and AEMO, in explicitly recognising DR in the dispatch and pricing process.

- An alternative way of settling a DRM customer’s tariff with the retailer. The original proposal suggested retailers would charge DRM customers the full baseline of energy at their retail tariff. However changing retailer billing systems to insert a non-metered consumption was one of the more expensive parts of the proposal. The AEMC have proposed a means by which a similar outcome might be achieved without needing to change these systems. This is discussed below.

- The draft determination proposed implementation in 2022.

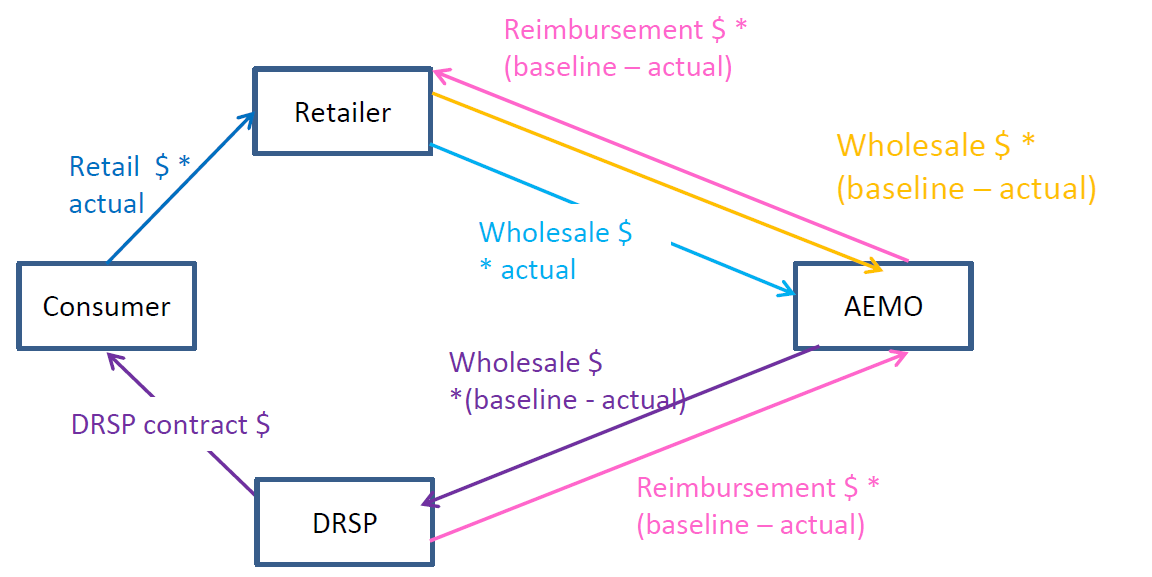

Reimbursement Arrangement

Source: AEMC

Source: AEMC

The significant change in the proposed design are in three new arrows above:

- The dark blue arrow from Consumer to Retailer is intended to be based on the actual consumption, rather than baseline consumption. This is to avoid the systems implementation cost as discussed above. But this alone would clearly be unfair on the retailer as it would be billing the customer for less energy than it is paying AEMO (the sum of the light blue and yellow arrows).

- This loss is offset by the retailer receiving a new payment from AEMO (pink arrow), which will be the (baseline energy – actual energy) * a “reimbursement” price. This reimbursement price is supposed to replicate the consumer’s retail tariff, thereby putting the retailer in a similar position as if it was collecting the whole baseline energy * retail tariff from the customer.

- Finally, that pink arrow amount is collected, by AEMO, from the DRSP.

This “reimbursement” price cannot be the actual retail tariff, as that is confidential and if used would be revealed to many parties. Instead the AEMC is suggesting it be an indicative current price for the wholesale component of retail tariffs, set by the AER. So, it’s a valiant attempt, but even after a lot of work by the AER and presumably contested argument with industry, it will never be exactly the tariff needed to make the retailer whole.

Conclusion

Given the pressure from many sides, it is perhaps not surprising that the AEMC was minded to make the draft rule. However they have also realised the significant implementation challenges and have attempted to ameliorate this with the implementation features described above.

The reimbursement arrangement certainly adds complexity to an already complex settlement arrangement. Yet, in proposing it, the AEMC may well be correct; that it could actually lower implementation costs for retailers and the proposal thereby be improved by it.

However unpacking such complexity reveals the trouble with the overall DRM concept. Whilst supportive parties such as Finkel and the ACCC rightfully wish to support DR, it is unclear whether they have fully grasped just how complex and unintuitive the DRM concept is, or whether they have been influenced by the “David vs Goliath” narrative run by its supporters.

View the AEMC’s draft determination on the Wholesale Demand Response Mechanism here

[i] AEMO, Demand-side Portal, accessed 16 July 2019

[ii] AEC, Electricity baseliners: Not as accurate as a Barty forehand, 27 June 2019

[iii] Commonwealth of Australia, Independent Review into the Future Security of the National Electricity Market, June 2017

[iv] AEMC, Reliability Frameworks Review, accessed 16 July 2019

[v] ACCC, Retail Electricity Pricing Inquiry - Final Report, June 2018

[vi] AEMC, Wholesale demand response mechanism, accessed 16 July 2019

[vii] AFR, Ben Potter, Big power wants gatekeeper role, 26 Oct 2018; AFR, Ben Potter, Power cartel takes aim at AEMC wholesale 'demand response' plan 31 May 2018; ABC, 7.30, Power Price Battle, 24 June 2019

Related Analysis

Is increased volatility the new norm?

This year has showcased an increased level of volatility in the National Electricity Market (NEM). To date we have seen significant fluctuations in spot prices with prices hitting both maximum price caps on several occasions and ongoing growth in periods of negative prices with generation being curtailed at times. We took a closer look at why this is happening and the impact this could have on the grid in the future.

Is there a better way to manage AEMO’s costs?

The market operator performs a vital role in managing the electricity and gas systems and markets across Australia. In WA, AEMO recovers the costs of performing its functions via fees paid by market participants, based on expenditure approved by the State’s Economic Regulation Authority. In the last few years, AEMO’s costs have sky-rocketed in WA driven in part by the amount of market reform and the challenges of budgeting projects that are not adequately defined. Here we take a look at how AEMO’s costs have escalated, proposed changes to the allowable revenue framework, and what can be done to keep a lid on costs.

Retail protection reviews – A view from the frontline

The Australian Energy Regulator (AER) and the Essential Services Commission (ESC) have released separate papers to review and consult on changes to their respective regulation around payment difficulty. Many elements of the proposed changes focus on the interactions between an energy retailer’s call-centre and their hardship customers, we visited one of these call centres to understand how these frameworks are implemented in practice. Drawing on this experience, we take a look at the reviews that are underway.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.