WA Electricity Reform: Have we got DER covered?

Uncertainty around energy policy has had an impact on all levels of the nation’s electricity supply systems. It has led to increased speculation about future reliability, electricity shortages, as well as assertions of power quality problems from the influx of renewables, even debate about the potential for blackouts as the energy mix continues to change[i].

Amidst all this, there is a growing focus on Distributed Energy Resources[ii] (DER) and their potential to help support and even expand high quality, reliable electricity supply.

Recently the Australian Energy Council and Synergies Economic Consulting hosted an expert panel to discuss DER development in the context of Western Australia’s electricity reform. In this first of a two-part look at DER we consider some of the key technical and wholesale market challenges[iii]. Subsequently we will take a look at the implications for customers as well as what customers are indicating they want from the energy supply changes that are underway.

Why DER?

DER has some advantages in an environment of uncertainty around large-scale generation investment. It can be a faster, less expensive option to the construction of larger centralised power plants, or an alternative to extending high-voltage transmission lines and even to distribution systems, particularly at edge of the grid.

DER also has the potential to offer customers lower cost, reliable, efficient energy, as well as the prospect of energy independence.

DER challenges

However, integrating DER faces significant challenges. Decisions about where and when to install DER and how to operate it are increasingly consequential, but many electricity customers lack the information, time and control to efficiently direct investment in, and operation of DER. The Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) has articulated a vision for a Single Integrated Platform (SIP) that integrates DER into the wholesale market. The platform will allow DER investment and operation to respond to market signals and provide operators with the means of centralised control as a last resort.

Aggregation and coordination of DER through emerging proprietary platforms could expand the reach and relevance of AEMO’s reforms by facilitating market participation through an interface accessible to small consumers and DER owners. However, DER can also distort efficient outcomes for consumers if we do not get the policy framework right.

DER owners presently face inefficient price signals and receive a range of services free of cost, such as ancillary services and capacity firming. This not only skews today’s investment decisions, but also changes the incentives to participate in market-based platforms.

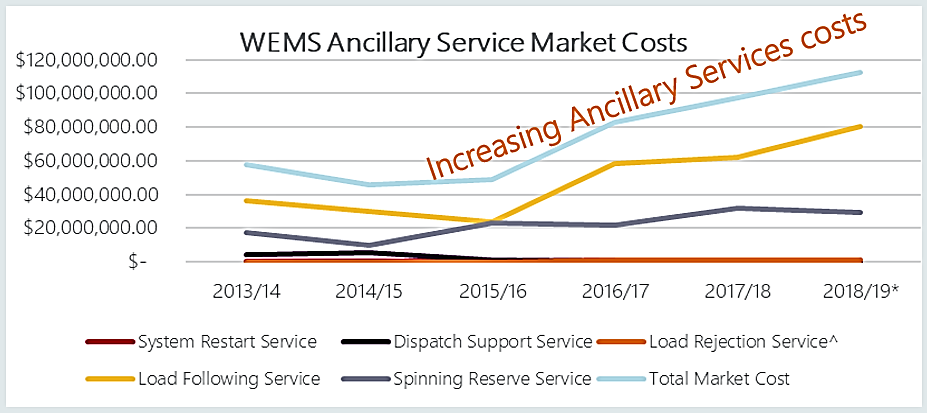

DER also undermines the commercial viability of synchronous generators that currently supply the market with several unpriced, but valuable, ancillary services, such as inertia and fault current. The cost of buying these services from new sources is not factored into DER investment choices and as you can see in figure 1 the costs of these services have already been growing over time.

Figure 1: WEMS ancillary service market costs

Source: AEMO slide

Source: AEMO slide

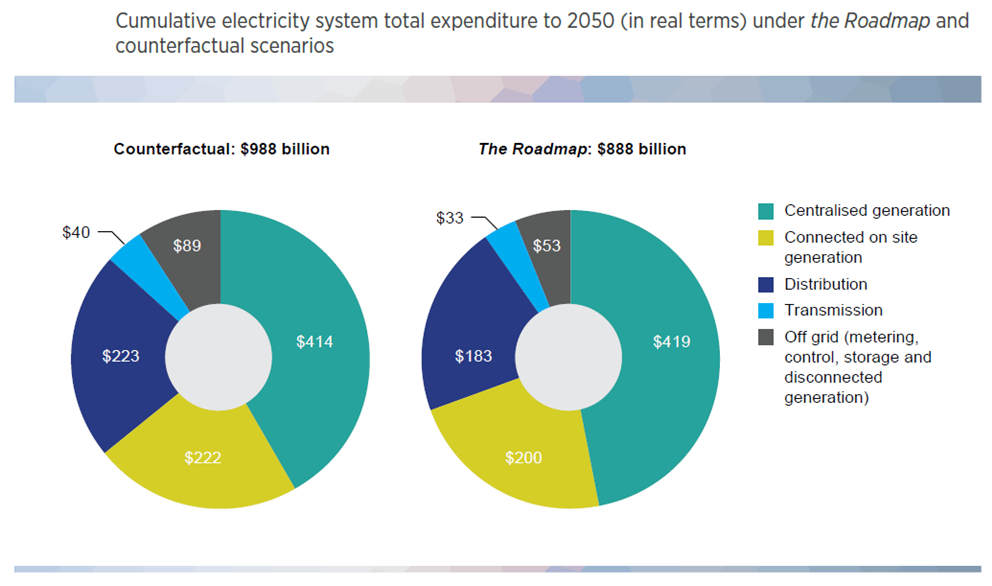

Overall, costs could increase if the approach to DER integration is inefficient – but there is an opportunity to get costs down. Energy Networks Australia’s (ENA) energy transformation roadmap has identified a potential for $100 billions of savings nationally, out to 2050.

Figure 2: DER - Friend or foe?

Source: Electricity Network Transformation Roadmap: Final Report; Western Power slide

Source: Electricity Network Transformation Roadmap: Final Report; Western Power slide

At the same time, DER opportunities are not evenly distributed, raising the prospect of DER-haves and have-nots. Rooftop solar forms part of DER and debate already exists over where the costs and benefits of solar PV is accruing and how the uptake of batteries and EV’s could add to this further these impacts. If we get the policies right, we stand to gain from the benefits of DER. However, this change is happening quickly.

Background

Uptake of rooftop solar in WA continues to grow steadily, with 1025 MW[iv] of installed capacity in WA’s South-West Interconnected System[v] (SWIS) at the end of 2018. This is more than three times the biggest conventional facility.

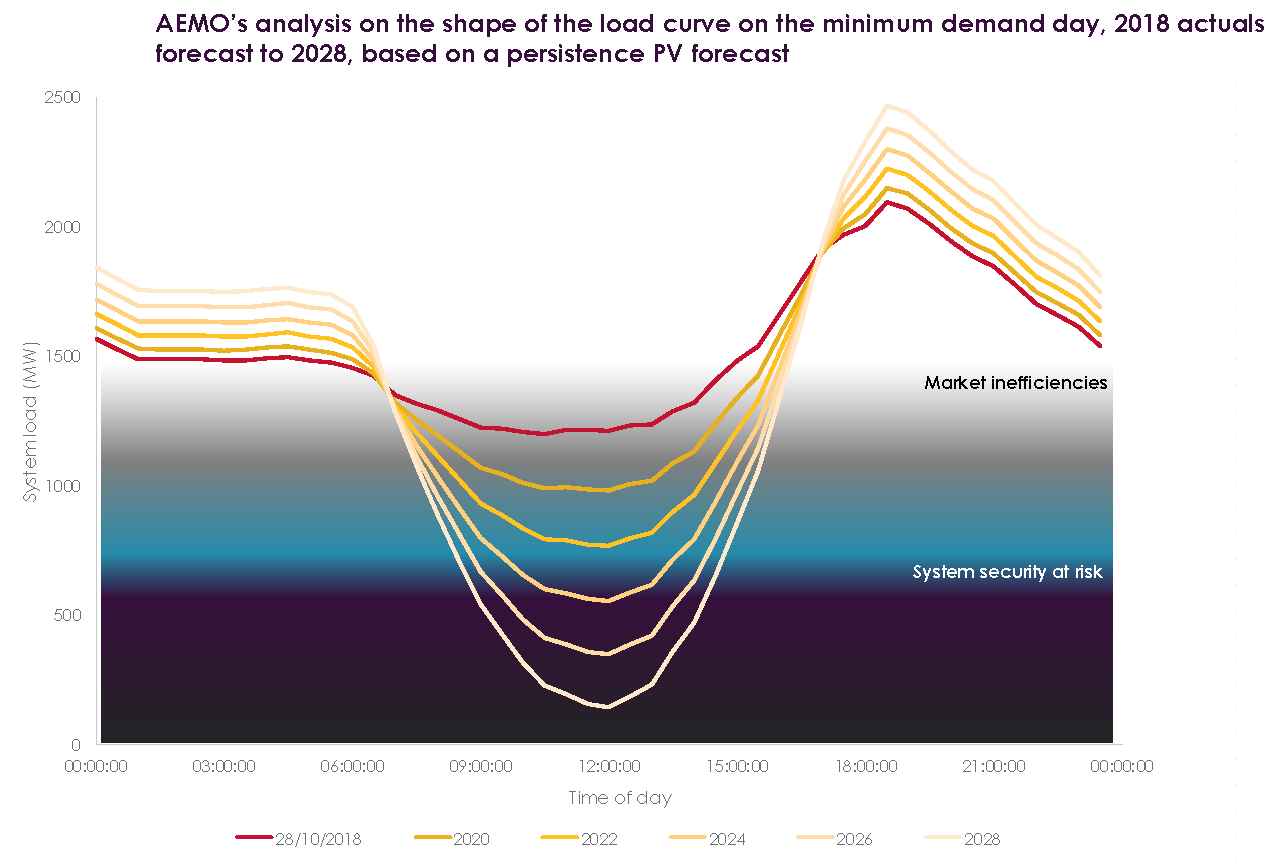

Figure 3: WEM Forecast Load Profile

Source: AEMO

Source: AEMO

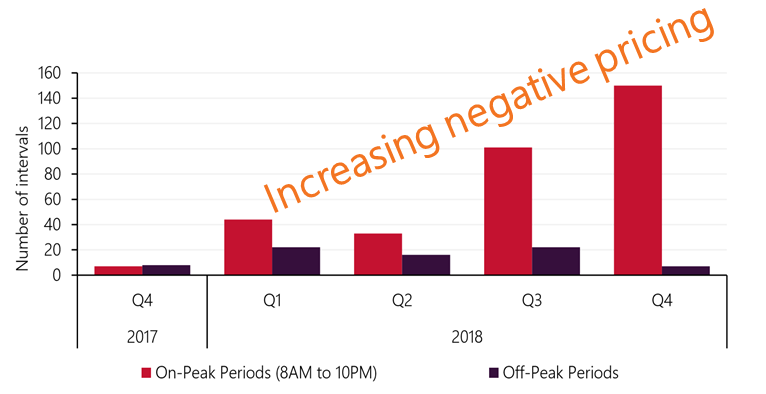

This amount of rooftop solar is beginning to have noticeable impacts on the operation of the system and the WA market and this impact is illustrated in figure 3 above. It is forecast to have greater impacts to market efficiency and system security in future. In September 2018, residential and small business customers generated more electricity than they consumed, so they were net generators for the month. Also, in the fourth quarter there were 150 on-peak intervals that were negatively priced in the balancing market (shown in figure 4), with November recording an interval priced at minus $65.47/MWh at 1200hrs. Backup Load Following Ancillary Services (LFAS) were called for the first time in the WEM, and were called upon twice during the quarter.

Figure 4: WEM negative Balancing Price Intervals

Source: AEMO

Source: AEMO

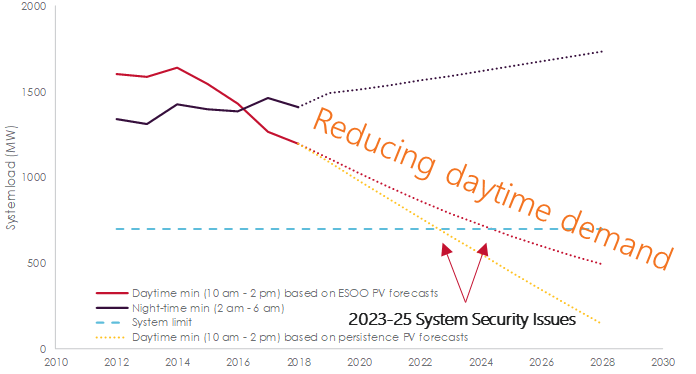

We are used to talking about reliability in the context of peak demand, but with this influx of new generation, minimum demand is the new peak demand. This introduces concerns for system security (the ability to ride through a credible disturbance to the system). As the demand on the system becomes smaller, the size of a contingency event relative to that demand is bigger, making it more challenging to ride through an event. According to AEMO forecasts, we could start seeing problems in the next three to six years with respect to maintaining system security during the middle of the day, which is shown in figure 5 below.

Figure 5: Minimum October demand each year

Source: AEMO

Source: AEMO

As volatility of demand increases ancillary services are relied upon to manage it. And as already noted the cost of these services is increasing. To add to this, the WEM’s wholesale market design was not developed for an increasing volume of asynchronous generation, so the ancillary services framework in place today isn't really fit for this changing power system.

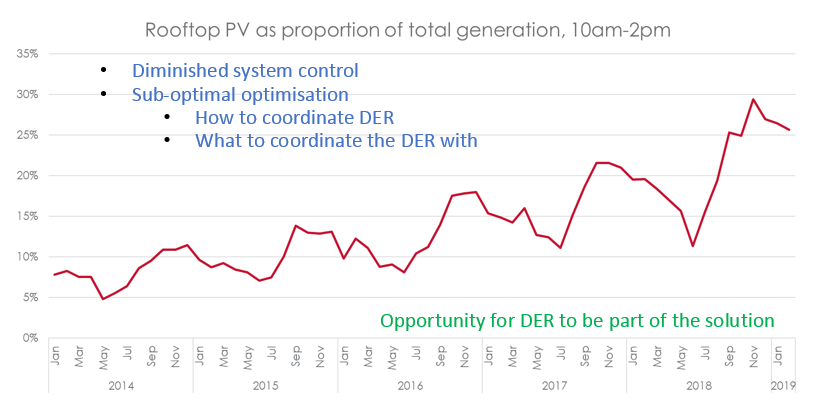

Already more than a quarter of the system generation on the grid sits outside the wholesale market and dispatch processes, and it can be 40 per cent on some days. The system is becoming more difficult and complex to manage and this is forecast to become even more complex as more rooftop solar connects to the system as more storage devices are installed. As a result AEMO’s ability to control the system will be diminished.

Figure 6: Address challenges, harness opportunities

Source: AEMO slide

Source: AEMO slide

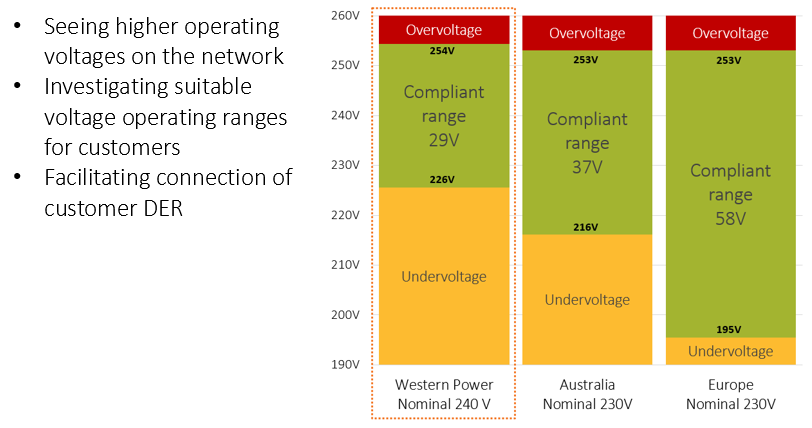

Over the last five to ten years the voltage on the network has increased slowly, driven in large part by the uptake of rooftop solar and the corresponding reduction in load in the distribution network. With the voltage heading toward the upper limit of 254 volts (WA nominal voltage is 240 volts) Western Power, which operates the distribution network in the south-west, is exploring the most appropriate voltage for the network going forward. This is expected to help facilitate higher amounts of DER connection to its distribution network.

Figure 7: Networks feel it first

Source: Western Power slide

Source: Western Power slide

Conclusion

The technical challenges of a high DER future are well understood and there is confidence that solutions can be developed that are up to the task of managing system security and reliability as more DER enters the system.

The most challenging issue appears to be understanding the seriousness of the various market distortions as a result of direct subsidies, cross-subsidies and free services that DER receives. As DER reduces the size of the pie being optimised in the wholesale market, such distortions are expected to become more and more consequential when determining how well all customers are provided with affordable, secure and sustainable energy.

[i] “It’s a state on the blink”, Weekend West, 23 March 2019

[ii] Definition of DER: By ‘distributed’ we mean connected to consumers on the distribution network, and we imply small scale and a diversity of locations and technologies. ‘Energy’ refers to both the release and absorption of energy. ‘Resources’ means being put to a useful purpose. Some examples therefore could include inverter-based generation, batteries, controlled small loads and electric vehicles.

[iii] A summary video of the panel discussion is available here. Event filming provided by Jurgen van Pletsen at www.PerthVideo.com.au

[iv] The absolute system maximum demand recorded in the South West Interconnected System was 4,006 MW

[v] The South-West Interconnected System commenced operations in September 2006 and covers the major population centres in WA, including Perth and an area from Albany in the south, to Kalbarri to the north and Kalgoorlie to the east.

Related Analysis

Data Centres and Energy Demand – What’s Needed?

The growth in data centres brings with it increased energy demands and as a result the use of power has become the number one issue for their operators globally. Australia is seen as a country that will continue to see growth in data centres and Morgan Stanley Research has taken a detailed look at both the anticipated growth in data centres in Australia and what it might mean for our grid. We take a closer look.

Energy Dynamics Report - A Tale of Minimum Operational Demand and Wholesale Price declines

The third quarter saw significant price declines compared with the corresponding quarter in 2022 right across the NEM. At the same time with increased output from solar and wind generation inin Queensland’s case, minimum operational demand records were set or equaled in every region. The quarter also saw the highest-ever level of negative price intervals with all regions showing an increase. We dive in to the pricing and operational demand detail of AEMO’s Q3 Quarterly Energy Dynamics Report.

Data centres: A 24hr power source?

Data centres play a critical role in enabling the storage and processing of vast amounts of online data. However they are also known for their significant energy consumption, which has raised concerns about their environmental impact and operating costs. But can data centres be fully sustainable, or even a source of power?

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.