Victorian Retail Energy: The times they are a changin'

The Essential Services Commission (ESC) released its Victorian Energy Market Update last week, representing the state of the retail market from January to March 2018.

The ESC published this report with an emphasis on discounting practices, and in particular its finding that large discounts don’t necessarily equate to lower prices for customers. The ESC also sought to highlight disconnection rates for the same period.

Concerns about discounting are not new. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s (ACCC) preliminary report from its Retail Electricity Pricing Inquiry, found that the practice of discounting was confusing to some consumers. This sentiment was also echoed in the Australian Energy Market Commission’s (AEMC) 2018 National Retail Energy Competition Review. The Prime Minister’s industry roundtables in August 2017 had also focussed on energy affordability, and the perception of customers that the market was difficult to engage with, and that discounting practices were confusing.

But things are changing. Retailers and policymakers alike are working towards sensible ways of expressing offers to small customers that are clear and easy to understand, whilst also being accurate, given electricity as a product is priced differently in across multiple network areas[i] and at different times of the day.

Achieving a more user-friendly market takes time, and the cooperation of industry and policymakers alike. In a complex market with a large variety of pricing bands and distribution areas, the ability to express offers simply and accurately has its challenges.

It should also be noted that Victoria runs a separate consumer protection regime to Tasmania, New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia and the ACT, which are part of the National Energy Customer Framework (NECF). This means that there are two parallel processes underway, with associated additional costs for retailers that operate in Victoria as well as other States.

Reforms underway

Despite the hurdles, reforms are underway. The Australian Energy Regulator (AER) published its updated Retail Pricing Information Guidelines in April 2018. The RPIG is part of NECF, and does not apply in Victoria. For the NECF jurisdictions, it specifies how retailers report their energy tariffs. Changes include:

- the introduction of the Basic Plan Information document and the Detailed Plan Information document.

- a 'comparison pricing table' with an indicative annual bill, in dollars.

- requirements for clearer and simpler language.

The Prime Minister’s Roundtables in 2017 also required retailers to write to customers whose discount benefit period had rolled off, to enable them to move to a better market offer. This initiative has meant around 230,000 customers are no longer on standing offers nationally – consistent with the ESC’s report that 5.8 per cent of residential customers were on standing offers in Victoria in the January – March quarter.

Declining standing offer numbers (they have come down from 6.6 per cent in the same quarter in Victoria last year) is good news. The reduction demonstrates increasing engagement by consumers with the market. This engagement may be a by-product of media and government (both State and Federal) attention over the last year, along with retailer efforts to highlight the competitive offers available.

As retailers work their way through the simplification of offers, the Victorian Government included in its budget a measure to motivate Victorian consumers to use the Victorian Energy Compare site to establish if there are better deals available for their situation. The $50 Power Saving Bonus (available until 31 December 2018) has resulted in higher than usual call volumes to retailers since it began on 1 July, and it is reasonable to assume that a percentage of people who log on to the government comparator site to receive their rebate will also take the time to plug in their data and switch to a cheaper market offer for their circumstances.

The new trend in market offers

Retailers are listening to the concerns of customers, and accept that discounting is a practice that, whilst appealing to some sectors of the market, can be confusing to others.

Apart from working on reforms to increase market transparency and accessibility, retailers are increasingly putting ‘no discount’ offers into the market. The AEMC’s 2018 report found that 20 per cent of market offers have no discounts attached to them and most retailers now have at least one undiscounted product in the market.

This trend is likely to continue to grow given the widely held view that discounting practices don’t work for all customers. However, retailers do report that some customers remain attracted to offers expressed in terms of discounts (even if it is explained that the ‘no discount’ offer may be cheaper) and prefer pay on time discounts.

The ESC Perspective

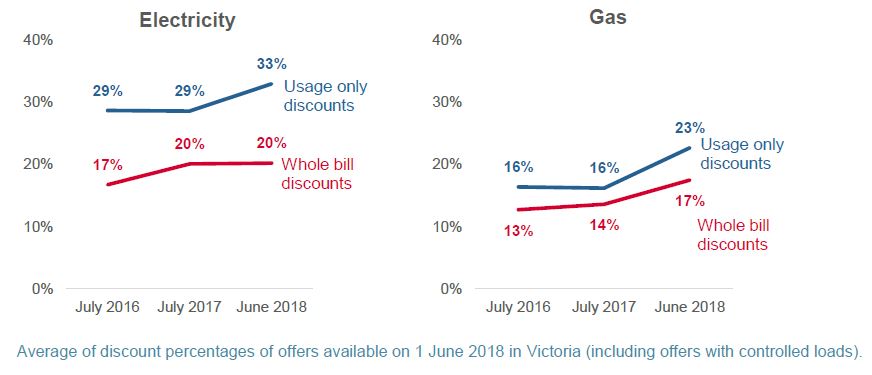

In its report, the ESC is keen to outline inconsistencies in how market offers are expressed in Victoria. Firstly, it has analysed average discount percentages of all Victorian energy offers since 2016:

Figure 1: Average discount percentages of all Victorian offers since July 2016

Source: ESC

Average of discount percentages of offers available on 1 June 2018 in Victoria (including offers with controlled loads).

This is not a particularly helpful table, as the standing offers will change from year to year depending on the inputs for retailers, in particular wholesale and network charges.

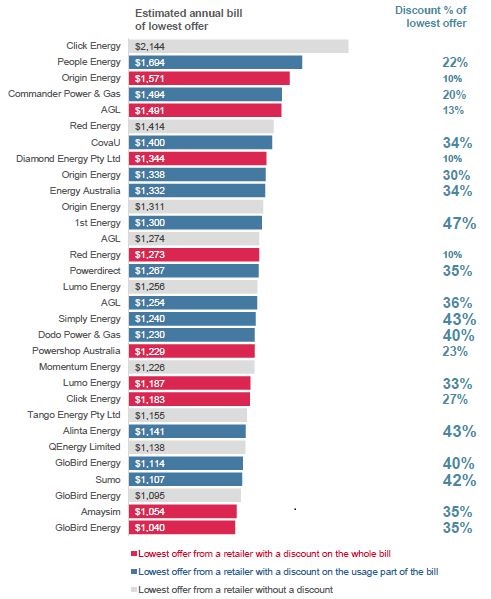

It then goes on to list the lowest offer for an average consumption for each Victorian retailer, together with the discount offered in this table:

Figure 2: Rank of retailers’ lowest electricity offers by discount percentage and estimated annual bills when conditions are met (available as at 1 June 2018)

Source: ESC

The chart separately shows the lowest offer from a retailer with discounts on the whole bill, with discounts on the usage part of the bill, and offers without a discount. Bill estimates are based on a typical residential customer using 4,000 kWh per year for all generally available electricity offers available on 1 June 2018 in the United Energy area (excluding offers with controlled loads), including GST.

This table illustrates the challenge for consumers in deciding on the best offer, absent the assistance of a comparator site. The discounts are more consistent if offers are grouped by the three types of offers in the market:

- Discounts on a whole bill

- Discounts on the usage part of the bill

- Market offers with no discounts

Within these separate categories there is a broad correlation between the cheapest offers and the discounts they include – any variances are of course because retailers are discounting off their own standing offer rates, which can vary from retailer to retailer.

Again this leads us back to the value of the government run comparator sites (both the Victorian Energy Compare site and the Australian Energy Regulator’s equivalent, which applies to the NECF States) , which cut through this confusion by benchmarking all offers against an assessment relevant to a customers’ circumstances. So there are mechanisms in place to make comparisons for an informed decision.

Disconnections

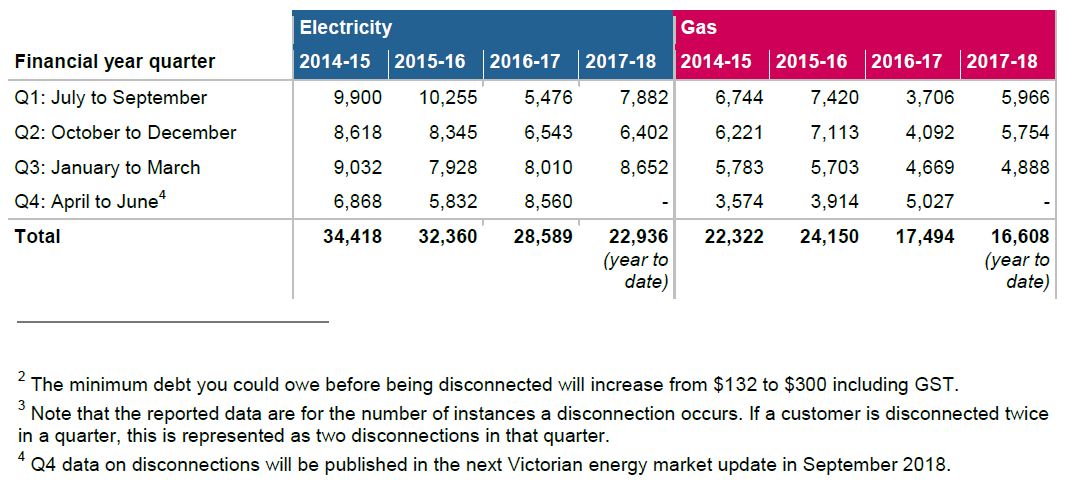

Another area of focus in the ESC report is disconnections. It shows that 13,540 Victorian households were disconnected in the most recent quarter from either gas or electricity, an increase from that quarter the previous year (which saw 12,679 disconnections). This figure was also a slight increase from the previous quarter which recorded 12,156 disconnections.

Table 1: Residential disconnections for non-payment, per quarter

Source: ESC

Source: ESC

Overall disconnections are tracking slightly higher than they were in the last financial year, but they are much lower than the numbers recorded in 2014-15 and 2015-16, which is positive. Ideally there would never be a need to disconnect an electricity account. However, avoiding disconnection can potentially risk higher customer debt as customers are kept on supply indefinitely, while continuing to use energy. This has ramifications for both the retailer and the customer.

The ESC’s report noted that, of the customers participating in hardship programs in July 2017 – March 2018, half had debts of over $1,000 (up from 43 per cent in 2016-17) and around a third of hardship program customers with payment plans are on these plans for one to two years.

An important barometer of retailer performance is wrongful disconnections. The ESC reports that 145 customers were wrongfully disconnected in Victoria in the January to March quarter (141 in the same quarter last year). Of those the ESC was asked to resolve five wrongful disconnection cases. The ESC upheld three in the customers favour.

The ESC made changes to the Energy Retail Code to increase the minimum debt amount for disconnection to $300 – it previously sat at $120. This increase in the threshold should see fewer cases of disconnections for minor or inconsequential debt levels in the future.

Conclusion

The balance between disconnection and hardship programs is a delicate one. While disconnection is used as a last resort, retailers understand that for some customers, a disconnection warning notice can act as a prompt for communication with a retailer (and encourage a conversation which may produce a manageable and agreed payment plans).

There will be a focus on Victoria’s new hardship framework to see if it delivers better outcomes for vulnerable customers in 2019. If a new framework limits a retailers’ ability to engage with customers early in the debt cycle, then customer debt levels may rise to unmanageable levels for some vulnerable customers.

Amidst all of the reform activity, it is worth noting that retailers operate in a world of volatile and (until recently) rising wholesale energy costs. These in turn lead to increasing bill shock for some households. These are not the fault of retailers, but a by-product of the significant changes underway in the energy industry. Increasing household cost pressures remain a broader social issue for both State and Federal Governments, which the energy industry cannot resolve.

[i] In Victoria alone there are five electricity distributors. In the National Electricity Market there are 14 distribution companies.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.