Transitioning with gas: What role will it play?

There has been much discussion in the press recently[i] about whether gas is, or should be, a transition fuel from coal-fired generation to a predominantly renewable energy-based future. Is it? Should it be? Could it be? We answer those questions and more.

Discussion

There are currently 76 gas-fired generation units in the National Electricity Market (NEM), making up 10,600MW or 25 per cent of the total scheduled generation. These generators have different ages and capabilities, ranging from the 120MW Torrens Island “A” steam turbine units built in 1967, to the latest 210MW Barker Inlet Power Station reciprocating engine units, which were commissioned late last year.[ii]

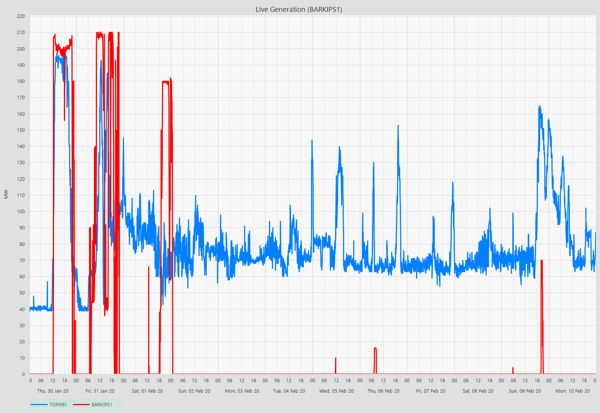

Having different technologies, the plants have different running patterns, for example during the period 30 January-10 February this year, Torrens B1 ran steadily, flexing up and down as needed, whereas Barker Inlet switched on and off as required, as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Torrens Island B1 and Barker Inlet Power Stations 30 minute generation

Source: AEC analysis of NEO data

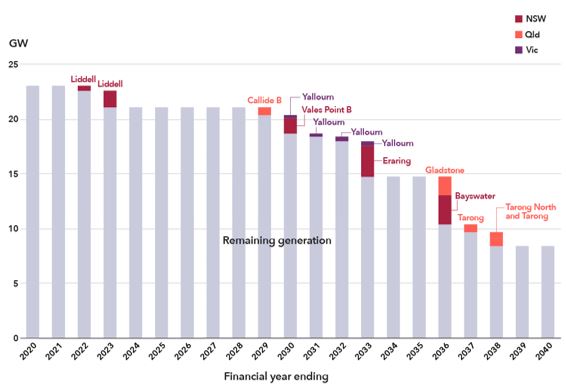

It is accepted that the NEM’s fleet of coal-fired generation will reach the end of its technical life in the next 40 years, and the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) has published its expectation of the retirement profile in the Draft Integrated System Plan (ISP).[iii]

Figure 2: Coal-fired Generation remaining as Power Stations retire

Source: AEMO, ISP

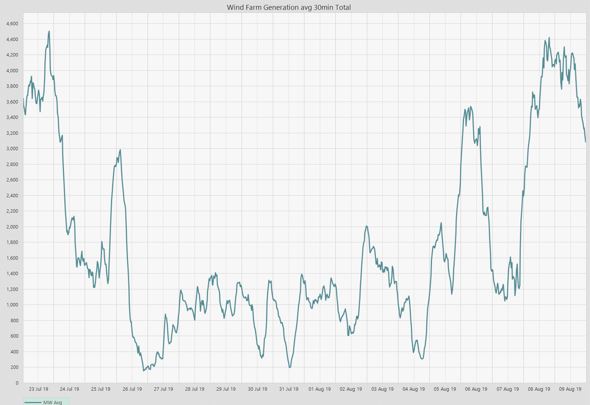

While there is a growing collection of renewable energy plants available to provide replacement energy, such plant cannot always be relied upon, for example in the middle of last year, when wind generation across the NEM quartered for a week.

Figure 3: Wind Farm Generation

Source: AEC analysis of NEO data

Wind diversity across regions, as facilitated by the proposals for increasing interconnection, can only go so far, as discussed in a recent Energy Insider article. This reported that across regions wind generation (and indeed other renewable generation) is correlated, meaning that renewable generation in other states cannot be relied upon to make up any generation shortfall.

Thus the market must turn to other sources, being batteries, hydro and gas.

Each technology has its own strengths and limitations. For example, batteries are very responsive, but their duration is limited, as discussed in this Energy Insider article. Hydro, and in particular pumped hydro, has more opportunity to be called into action when needed, but site availability and environmental considerations must be overcome to install new plant. The NEM currently has 7,600MW of hydro plant (800MW of which is pumped), with Snowy 2.0 to add a further 2,000MW of capacity.

Gas-fired plant is discrete and, to some extent portable. For example, the SA Temporary Generation plant has been relocated, following the signing of 25-year leases with private companies.[iv]

However unless it is dual-fuelled, it does not have fuel onsite (as hydro does) or have the ability to replenish itself, as batteries do. Instead it must rely on the extraction of natural gas from sources which are generally distant from the generation site, and have the natural gas hauled to site via transmission pipelines.

In comparison with batteries and hydro, natural gas generation also has an associated emissions intensity, which draws scrutiny from critics. This emissions intensity is of the order of 0.429tCO2-e/MWh (CCGT) to 0.583tCO2-e/MWh (OCGT),[v] but gas peaking plants, which facilitate the transition from coal-fired generators (which have emissions intensities in the order of 0.9tCO2-e/MWh to 1.5tCO2-e/MWh)[vi] to renewable generation because they are flexible and fast-start, are run for only limited periods, therefore their overall contribution to emissions is significantly lower.

The International Energy Agency has recognised the utility of gas-fired generation as a transitional technology in its report, The Oil and Gas Industry in Energy Transitions.[vii] The report says,

“The role of gas in the power sector in the SDS[viii] varies by country, depending on prevailing prices and policies, but there is a general shift towards the provision of balancing and flexibility functions for both seasonal and short-term variations in demand, rather than the provision of baseload or mid-merit power. As variable renewables scale up rapidly, gas infrastructure plays a crucial role in ensuring security of electricity supply.”[ix]

It concludes that,

- the oil and gas industry will be critical for key capital-intensive clean energy technologies to reach maturity; and

- without the oil and gas industry, the transformation of the energy sector will be more difficult and more expensive.[x]

Conclusion

While natural gas and gas-fired generation have their disadvantages, so too do other fuel sources and generation technologies. As the power system currently stands, renewable generation needs to be supplemented to provide a similar output certainty to conventional plant, and natural gas is one method by which the transition to more renewable energy can be facilitated. The extent to which it can do this will depend on the extent of the role of gas in the power system will be dependent on the availability of supply, transportation and storage infrastructure, as well as the cost of the gas and its transportation.

[i] “More gas the key to mitigating climate risk: PM”, Australian Financial Review, 29 January 2020; “Scott Morrison is stuck in a time warp – more gas is not the answer”, The Guardian Opinion, 2 February 2020

[ii] https://www.aemo.com.au/energy-systems/electricity/national-electricity-market-nem/nem-forecasting-and-planning/forecasting-and-planning-data/generation-information

[iii] AEMO, Draft 2020 Integrated System Plan, 12th December 2019

[iv] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-08-28/back-up-power-generators-leased-to-private-companies/11457824

[v] Schandl, H., Baynes, T., Haque, N., Barrett, D. & Geschke, A., Final Report for GISERA Project G2 – Whole of Life Greenhouse Gas Emissions Assessment of a Coal Seam Gas to Liquefied Natural Gas Project in the Surat Basin, Queensland, Australia, July 2019, p.23, Table 13

[vi] Environment Victoria, Submission to the Inquiry into the Retirement of Coal-fired Power Stations, 10th November 2016, p.5, Figure 1

[vii] International Energy Agency, The Oil and Gas Industry in Energy Transitions – Insights from IEA Analysis, January 2020

[viii] The World Energy Outlook Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS) charts a path fully consistent with the Paris Agreement by holding the rise in global temperatures to “well below 2°C … and pursuing efforts to limit [it] to 1.5°C”, and meets objectives related to universal energy access and cleaner air.

[ix] International Energy Agency (2020), p.67

[x] https://www.iea.org/reports/the-oil-and-gas-industry-in-energy-transitions#key-findings

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.