The NEM: Beyond 2025

The Australian Energy Council recently convened an expert panel to debate approaches to energy market design on the back of the Energy Security Board’s consideration of the future energy market design. The ESB has been asked by the COAG Energy Council to recommend any changes to the existing market or alternative designs to deliver a secure, reliable and lower emissions electricity system at least cost. Below are perspectives on market design that emerged from the panel discussion.

Alex Cruickshank, Principal Consultant, Oakley Greenwood

The Australian NEM is not alone in needing to change as a result of new developments and the increasing cost of electricity. Markets around the world are refocusing to the edge of the grid as technology develops and the old paradigm that centrally supplied energy is the most efficient is giving way to a more nuanced approach where a mix of technologies and approaches provides the best solution. In addition, there is a felt need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in an attempt to forestall climate changes.

With the developments of technology, businesses are emerging that are seeking to assist businesses, communities and, eventually, individuals to optimise their use. This will lead to a rise in the use of PV, storage and demand response.

The emerging issue with uncoordinated developments is a reduction in reliability and security of the electricity grid. At the same time, the deteriorating investment environment and the costs of subsidies is leading to higher prices to consumers.

These impacts are being felt in many countries with energy markets. Those markets that grew organically and already had capacity remuneration are changing their mechanisms and markets that were efficiently designed as energy only are also adopting approaches to directly remunerate capacity. It is also worth noting that there is also a general increase in mechanisms to incorporate demand response into dispatch markets to improve the responsiveness to intermittent supplies. Two quotes summarise the debate:

"Energy only markets work in theory but not in practice."[1]

"Capacity remuneration is for people that don't believe in (trust) markets.”[2]

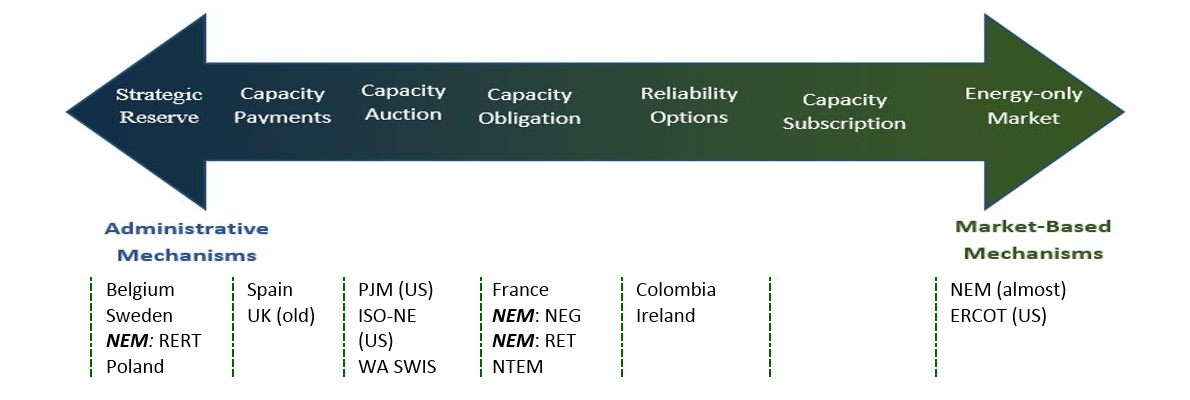

I use the term capacity remuneration, rather than capacity markets, as there are a range of approaches to supporting capacity development to assure reliability. The variety of mechanisms is also complicated by jurisdictions optimising their approaches by adopting variations. On a spectrum, the most comment types, and markets or countries that use them, can be shown[3] as:

All capacity remuneration mechanisms have their flaws, like the NEM, but many countries are starting to use them, or improving their current approaches, to address price and reliability issues. The decision should be based on the trade-off between the required reliability and the least-cost approach to achieve it.

Demand response is also increasing around the world, seen as a key factor in providing increased flexibility. The key aspects for efficient demand response is effective pricing, both in customer prices and for services provided by demand response, effective technical integration so that costs do not increase and measurement (or verification) of the quantity of demand response.

A lot of demand response is currently provided via retailers and aggregators into the energy and ancillary services markets in the NEM. Many overseas markets, however, have found the separation of the load serving entity (retailer) and the demand response provider (aggregator) leads to a large increase in the use of demand response.

Ben Skinner, General Manager Policy and Research, Australian Energy Council

My advice to those who seek change from the current market is: “Be careful what you wish for”. Centrally determining capacity requirements may seem comforting, but instead it introduces a host of new problems.

Whilst we call the existing NEM an “energy-only” market, it actually incorporates many ancillary services markets, and supports contracting markets run by participants.

There is clearly a need for more ancillary services, as electrical phenomena that could previously be taken for granted are now in short supply. The NEM’s rules always anticipated this, and empowers AEMO and Networks to go out to market to obtain them. The frequent interventions we are seeing have nothing to with the energy market design, they are only a symptom of how long it is taking these parties to exercise the powers they already have.

It is not unexpected that monopolies would struggle to keep up with all the changes in our industry, and this is exactly why we should rely less on their judgements at this time rather than more.

With respect to energy, the NEM’s processes already values and arranges it. And I mean energy in a broad sense, including:

- The capacity to supply energy as needed when the system is tightest;

- Balancing – at least for timeframes beyond the settlement interval, which includes:

- Ramping assets up and down;

- Starting and shutting down assets as needed.

How can an energy-only market do all that? With a bit of greed, and an awful lot of fear:

- Retailers fear paying $14,700/MWh, so they contract with a generator;

- Generators fear paying $14,700/MWh to a retailer when their assets are not receiving it; and

- Generators fear paying $1,000/MWh for running more assets than customers need.

Decentralised markets, such as the contract market which exists around the NEM, achieve all of the above through the magic of the invisible hand.

In the NEM, participants form their own view about their own customers and the performance of their own assets, under pain of $14,700/MWh. And who is better placed than them?

Consider the alternative. Central capacity mechanisms require authorities to perform these difficult analyses, subject as they are to information assymetry, conservatism and special pleadings. They are the very worst people to do such analyses – and I should know, I’ve been one.

When it was discovered, around 2005, in both South Australia and Western Australia that wind could not be relied upon for its average 33 per cent output at time of demand peak, the NEM’s contract markets immediately adjusted to discount it to near zero for firmness. In contrast, it took the Western Australian electricity market rule maker some eight years of contested argument to adjust its central capacity allocation down.

And now we welcome a whole host of new technologies to the NEM. How many hours of storage maketh the battery firm? What kinds of demand-side response are firm and with how much notice? When should an ageing coal unit’s reliability be discounted? Sure, these are hard questions for their owners to get right, but much harder for a regulator.

Something often forgotten by those who seize on capacity markets, is that introduction to the NEM would force a re-think of transmission access. The NEM’s network will never be capable of carrying every generators’ output simultaneously to customers, and so network capacity is rationed at dispatch time in the energy-only market. However dispatch is not available when allocating capacity years into the future. Allocating capacity rights would therefore in turn necessitate forward allocating transmission access – a highly controversial issue the NEM has never agreed upon.

That is not to say that transmission access rights are a bad thing, but that it is logically inconsistent to believe it is possible to provide forward generation capacity allocations without first resolving transmission access.

So, in conclusion, my advice is to not wander blithely into centralized capacity mechanisms without being aware of these great challenges that they bring. I agree this energy transformation under the energy-only market looks chaotic and unpredictable, but all history shows that the best manager of chaos is Adam Smith’s invisible hand.

Our existing market relies on decentralised decision-making. This seems the worst of times to centralise it.

The following is an edited summary of comments made by Professor Michael Brear, Director Melbourne Energy Institute at Melbourne University

Variable generation is challenging our system in ways that even the sharpest of sharpest power system engineering minds don’t fully understand. All the way from inter-year, long-term randomness in generation, to short-term randomness in their forecast of generation, through to how power electrics in these devices do strange things and don’t operate as assumed or intended, and then impact the system in many different ways. At the same time, there are a number of other dynamics going on in the system. It’s complicated.

With such increasing complexity and a technologically complex world, determining ‘resource adequacy’ or ‘capacity adequacy’ is an increasingly wicked problem, and it’s an area that very serious technical analysts are trying to improve all the time – some of them are in the Australian Energy Market Operator, or universities and other places around the world.

It’s also primarily an engineering problem and not an economic problem. Capacity assessment is a hard technical problem that requires very experienced people. Working out what we need in terms of capacity is easy to get wrong. Getting it wrong is probably of greater economic consequence to all of us, than if we have an energy only market, a capacity and energy market, or whether we have 10 or 15 ancillary services or not.

It’s also easy to get it wrong if one state minister says, “we need this kind of stuff”, and another state minister says “we need that kind of stuff”, and a federal minister says “we don’t need either of those, we need this instead” and either directly intervene in the market, or lean on people to push assessments in certain directions – observing the inconsistencies of such central policy makers almost comes across as possibly an argument against capacity markets.

But the engineer in me says there should be rigorous independent assessment of capacity adequacy and some means of implementing that assessment.

Relying on a retailer that may not fully understand it - I’m not convinced that’s the best way to do it.

I can’t see how retailers and financial markets can ensure the building of everything needed to ensure reliability and security, so I tend towards independent capacity assessment at the very least and maybe the awarding of contracts.

The retailer reliability obligation (RRO) in this context may be a least-worst option, with AEMO conducting the capacity assessment and retailers responsible for contracting of this capacity.

One thing that we can all agree is that a staged reform process is needed, underpinned by rigorous, transparent and independent analysis.

In my view, such a process should be conducted at a level above that which we typically see during rule changes, in which different parties often engage opposing consultants to argue their book.

The time has come for us all to stop putting our “two bobs worth” in, uninformed by this sort of rigorous analysis. If we get the analysis right, it will tell us what we need to do rather than all of us continuing to speculate.

Listen to the The NEM: Beyond 2025 full panel discussion podcast here.

[1] Gerard Doorman, the convener of WG C5-17 on capacity remuneration at the first meeting.

[2] Various attributions have been made for this quote, but I am going with Greg Thorpe from Oakley Greenwood.

[3] Based on Technical Brochure 647, “Capacity mechanisms – needs, solutions and state of affairs”, CIGRE 2016, www.e-cigre.org

Related Analysis

Certificate schemes – good for governments, but what about customers?

Retailer certificate schemes have been growing in popularity in recent years as a policy mechanism to help deliver the energy transition. The report puts forward some recommendations on how to improve the efficiency of these schemes. It also includes a deeper dive into the Victorian Energy Upgrades program and South Australian Retailer Energy Productivity Scheme.

2025 Election: A tale of two campaigns

The election has been called and the campaigning has started in earnest. With both major parties proposing a markedly different path to deliver the energy transition and to reach net zero, we take a look at what sits beneath the big headlines and analyse how the current Labor Government is tracking towards its targets, and how a potential future Coalition Government might deliver on their commitments.

The return of Trump: What does it mean for Australia’s 2035 target?

Donald Trump’s decisive election win has given him a mandate to enact sweeping policy changes, including in the energy sector, potentially altering the US’s energy landscape. His proposals, which include halting offshore wind projects, withdrawing the US from the Paris Climate Agreement and dismantling the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), could have a knock-on effect across the globe, as countries try to navigate a path towards net zero. So, what are his policies, and what do they mean for Australia’s own emission reduction targets? We take a look.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.