Tackling coal-fired emissions – No easy fixes

Australia is not the only place grappling with the challenge of transitioning from coal-fired generation given its current role in overall supply and the need to maintain reliability and affordability. The IEA has assessed the implications of tackling emissions from coal-fired power plants internationally.

Coal-fired power stations have been providing reliable, flexible and affordable electricity for more than a century and more recently they have helped bring access to electricity to hundreds of millions of people, particularly in Asia.

That is counterbalanced by the fact that they account for 30 per cent of energy-related carbon emissions and around a quarter of energy-related greenhouse gases overall.

The IEA notes that retrofitting coal-fired plants with carbon capture and storage technologies, repurposing plants to provide flexibility and in some cases phasing out plants early are options that might need to be considered to meet global emissions targets.

The scale of the capacity of coal-fired power stations poses significant challenges and coal plants are continuing to be developed. The IEC estimates that more than 170GW of coal plant capacity was under construction in 2018[i], which would be added to the existing international coal generation fleet which was sitting at 2080GW and “risk locking in another 15GT of CO2 emissions over the next two decades”[ii].

Given the international capacity of coal-fired power stations they remain the biggest source of electricity internationally, accounting for 38 per cent of total electricity generated – the same as it was in the 1970s[iii].

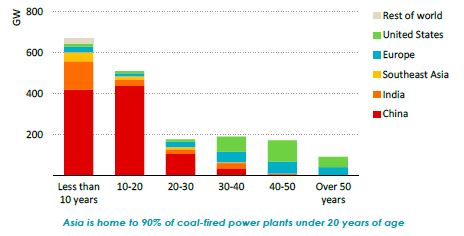

The other challenge in moving away from coal is that almost 60 per cent of the existing coal plants are around 20 years old or younger (see figure 1), while in developing Asian economies coal plants average 12 years (the estimated lifespan for a coal-fired plant is put at 50 years).

Over the past two decades, Asia accounted for 90 per cent of all new coal-fired power stations built worldwide (this involved 880GW being built in China, 173GW in India and 63GW in SE Asia, 28GW in Korea and 20.5GW in Japan). Outside of Asia Europe added 45GW of coal-fired capacity and the US added 25GW in that same period.

Figure 1 Global coal-fired power capacity by plant age, 2018

Source: IEA

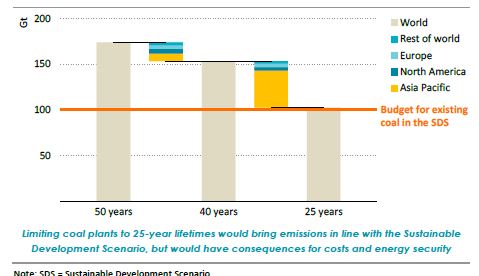

So how to tackle the emissions question while maintain supply reliability and affordability? As noted by the IEA the crucial question for tackling CO2 emissions is what average lifespan for the world’s coal-fired power plants would be compatible with international climate goals.

Capping the life of all existing plants to 25 years would bring emissions into line with the sustainable development scenario[iv], but applying a 40-year limit would see emissions exceeding climate goals by 50 per cent (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Cumulative CO2 Emissions from existing coal-fired power plants by assumed lifespan, 2019-2040

Source: IEA

While restricting the life of plants might have appeal because of its seeming simplicity, it obviously has major implications for energy costs and energy security. With almost 700GW of the capacity that is currently in operation being more than 25 years old shutting them down immediately (in line with the sustainable development scenario) would seriously impact energy security while also having significant financial implications for owners (both private and public).

The IEA believes several options could help in dealing with coal-plant emissions including carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) retrofitting or biomass co-firing equipment, changing their function to focus on providing power system adequacy and flexibility while reducing their output and retiring early if the other options don’t work.

But the IEA concedes the financial hurdles are high - the CCUS option could cost $1bn or more per gigawatt for a retrofit, while the cost of biomass co-firing or changing the function of the plants would cost millions per gigawatt.

CCUS would be most attractive for younger, more efficient coal-fired power plants located near places that have scope to use or store the carbon emissions. It would also demand enhanced public policy, such as preferential dispatch to ensure high utilisation rates for the plant, together with feed-in tariffs, capital grant funding and tax credits, according to the IEA. The IEA estimates the price tag for CCUS investment would be US$225bn to 2040.

Implementing retrofits, changing the role played by coal plants and introducing a retirement strategy to make the world’s coal-fired fleet compliant with climate goals would also lead to balance sheet writedowns and greater investment in lower-carbon sources of generation and associated network infrastructure. The IEA notes that more than US$1 trillion of capital invested in the existing coal fleet has yet to be recovered with most of the investment in Asia.

Putting aside the major financial barriers to the IEA options, the agency calculates that if applied CCUS could reduce emission by up to 99.7 per cent, biomass by 5-20 per cent while shifting the way coal-fired power stations are operated within the power system could lead to reductions of between 1-80 per cent.

Replacing coal plants will continue to be a major challenge and the subject of debate, not least because it is and has been a cheap source of electricity and the price tag of replacing existing facilities with new generation sources risks increasing overall supply costs while potentially reducing reliability.

The IEA makes the point that addressing emissions from coal power generation worldwide raises challenges for policy makers of how to finance the transition “which is global in scale and unevenly distributed geographically”. It warns that developing countries may face a significant share of the burden which raises yet another barrier to change.

[i] Outlook for Electricity, IEA World Energy Outlook 2019

[ii] International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook 2019, Global Trends

[iii] ibid

[iv] The Sustainable Development Scenario lays out a pathway to reach the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) most closely related to energy: achieving universal energy access (SDG 7), reducing the impacts of air pollution (SDG 3.9) and tackling climate change (SDG 13). It is designed to assess what is needed to meet these goals, including the Paris Agreement, in a realistic and cost effective way.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.