South Australia renewables: Incidental learnings

The Northern Power Station ceased operations at 9.30am on Monday 9 May 2016, after 31 years of providing South Australia with base load power. Increased utility scale wind and residential PV have made it difficult for coal-fired generation to remain competitive in South Australia, with Alinta pointing to the significant growth in renewables, along with declining demand leading to significant oversupply of generation assets in South Australia[i].

Increased utility scale wind, residential solar penetration and the exit of thermal generation has led to a unique combination of challenges in the South Australian energy market. Minimum and maximum demand forecasts from the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) indicate that minimum demand could be met entirely by residential solar panels in 2025, while the continued exit of thermal generation is forecast to lead to a supply adequacy breach by 2020 unless there is new investment in dispatchable generation[ii]. Below we take a look at the minimum and maximum demand issues facing South Australia.

Minimum demand

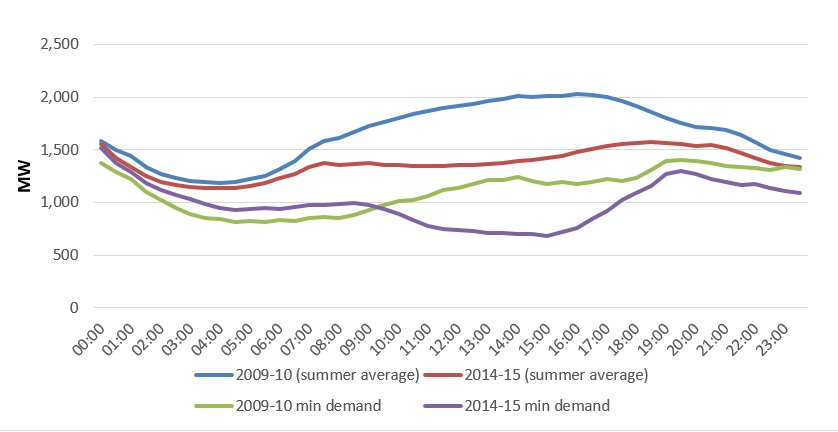

The timing of minimum demand is changing - previously minimum demand occurred during the night or early morning when households are not active and businesses are closed. With the increasing penetration of residential solar (some suburbs can reach in excess of 40 per cent penetration[iii]) the timing of minimum demand has shifted to early afternoon. Figure 1 shows the changing nature of demand in South Australia. The average trend line highlights the decline in consumption, while the comparison between days when minimum demand occurs highlights the shift in the timing of the lowest demand. In 2009-10 minimum demand occurred at 5:30am in the morning, five years later, minimum demand has moved to 3:00pm.

Figure 1: South Australia shifting demand 2009-11 vs 2014-15

Source: Australian Energy Council analysis of NEM-Review data

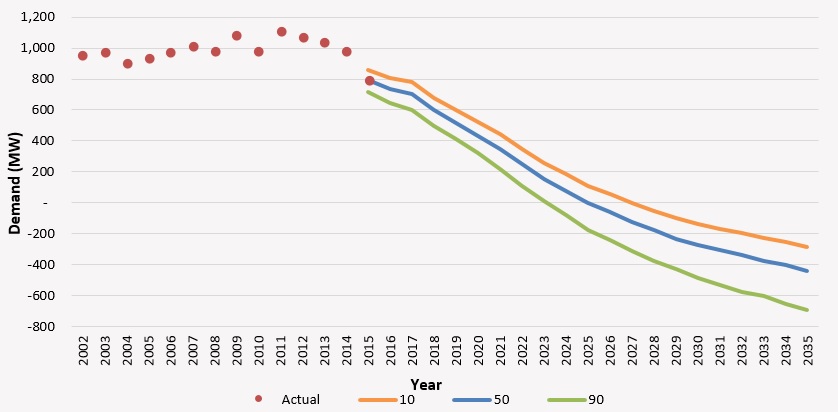

The declining trend has prompted AEMO to forecast minimum demand levels in South Australia for the first time in their National Energy Forecasting Report. By 2025, under the 50 per cent probability of exceedance scenario (POE) PV generation will exceed minimum load. Figure 2 shows AEMO’s forecast.

Figure 2: AEMO forecast of minimum demand

Source: AEMO

What is the problem with demand being met by residential solar?

Rooftop solar was never designed to meet the demand of an entire system. The electricity system is complex and constantly changing, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Demand changes every second due to changes in residential and commercial load. The degree of the changes varies significantly, from that caused by houses switching on lights and domestic appliances to changes resulting from large, energy intensive businesses, such as industrial customers.

Thermal generation provides inertia which ensures small or large changes in electricity demand do not interrupt energy supply. Inertia comes from spinning turbines which can be adjusted to match demand shifts where necessary. Rooftop PV generation does not provide inertia for the electricity grid. It cannot adjust to sudden changes in customer load. This means that if rooftop PV has displaced all thermal generation for a period and then there are changes in demand, the market operator has no-one it can call on to respond to maintain frequency levels. As long as the Heywood interconnector is operational, this will help, but it puts a lot of reliance on this one asset for system stability and security.

The phenomenon of rooftop PV meeting a region’s entire load has not been seen anywhere in the world, so there has been no solution offered. South Australia is the first of its kind and due to this, regulators and operators will be forced to come up with original solutions to ensure reliability in the future.

Maximum demand

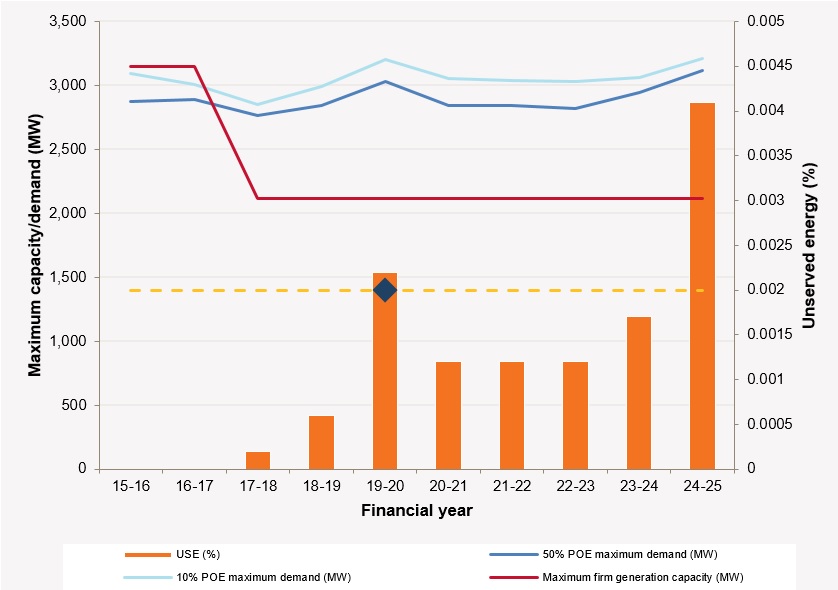

After several years in which we have seen an increasing oversupply of generation, the release of the 2015 Electricity Statement of Opportunity (ESOO) for Eastern Australia highlights that a return to supply/demand constraints may be on the horizon. Figure 3 shows the forecast Low Reserve Condition (LRC), which estimates a breach in South Australia in 2019-20. LRC is the term used when AEMO considers that a region's reserves fall short of what is required to meet the reliability standard.

Figure 3: South Australia generation adequacy

Source: AEMO

The decreased generation adequacy is caused by decreased firm capacity in the market. Firm capacity is the total generation capacity in a region (excluding wind), plus the historical wind capacity factor at times of peak demand multiplied by the wind capacity.

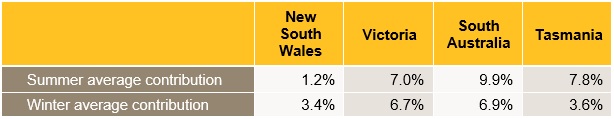

AEMO’s modelling uses NEM historical data to estimate the impact of the contribution of wind during times of peak demand. Table 2 shows the contribution of wind during peak demand in each region of the NEM. The data is representative of the capacity factor at times of peak demand, not of the share of total generation.

Table 1: 85 percentile wind contribution to operational maximum demand factors

Source: AEMO

The closure of the Northern Power Station, South Australia’s second largest power station, is a result of falling demand and continued growth of intermittent renewables in the market. Wind, which runs at zero marginal cost, has pushed baseload capacity further up the merit order, making it difficult for traditional generations to compete in the market and remain operational.

[i] Alinta Energy, Flinders Operations Announcement, https://www.alintaenergy.com.au/about-us/news/flinders-operations-announcement

[ii] AEMO, 2015 Electricity Statement of Opportunities, http://www.aemo.com.au/Electricity/Planning/Electricity-Statement-of-Opportunities

[iii] Australian PV Institute, Mapping Australian Photovoltaic installations, http://pv-map.apvi.org.au/historical#8/-35.317/138.933

Related Analysis

Certificate schemes – good for governments, but what about customers?

Retailer certificate schemes have been growing in popularity in recent years as a policy mechanism to help deliver the energy transition. The report puts forward some recommendations on how to improve the efficiency of these schemes. It also includes a deeper dive into the Victorian Energy Upgrades program and South Australian Retailer Energy Productivity Scheme.

The return of Trump: What does it mean for Australia’s 2035 target?

Donald Trump’s decisive election win has given him a mandate to enact sweeping policy changes, including in the energy sector, potentially altering the US’s energy landscape. His proposals, which include halting offshore wind projects, withdrawing the US from the Paris Climate Agreement and dismantling the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), could have a knock-on effect across the globe, as countries try to navigate a path towards net zero. So, what are his policies, and what do they mean for Australia’s own emission reduction targets? We take a look.

UK looks to revitalise its offshore wind sector

Last year, the UK’s offshore wind ambitions were setback when its renewable auction – Allocation Round 5 or AR5 – failed to attract any new offshore projects, a first for what had been a successful Contracts for Difference scheme. Now the UK Government has boosted the strike price for its current auction and boosted the overall budget for offshore projects. Will it succeed? We take a look.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.