SA energy plans: Ebony and Ivory

South Australia has become the “ground zero” of energy policy debate in Australia. It has a partially interconnected grid with the highest penetration of intermittent renewables in the world. South Australian consumers have experienced rising prices and increased blackouts over the past two years, most infamously the system black on 28 September last year. It’s unsurprising that energy policy has become a hot political battleground in the lead up to the state election next March.

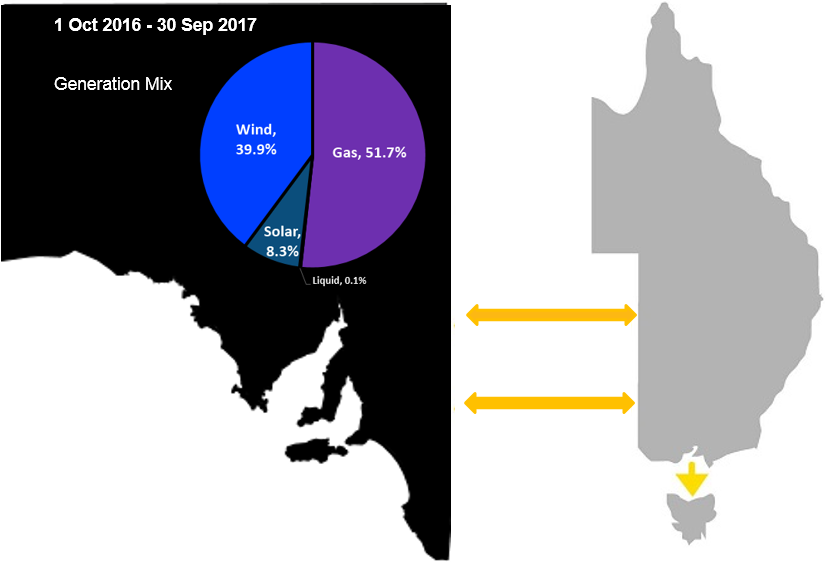

Figure 1: SA generation post coal

Source: NEM Review, AEMO

The fundamental challenge for both major parties is that South Australian energy policy is only weakly managed at the state level. The state is part of the National Electricity Market (NEM). Electricity supply and investment is increasingly impacted by national policy settings, or the absence thereof. The State’s 1700MW of wind and solar generation was facilitated by supportive state government planning laws and processes, but was fundamentally driven by a combination of the national Renewable Energy Target, the state’s historically higher wholesale prices in the NEM and access to good sites for wind and solar development.

The short term effect of this new generation was to suppress wholesale prices at times when the wind was blowing. However this in turn undermined the viability of the state’s firm generators - gas and coal - that were required to run hard when there was no wind and back right off or switch off when it was windy. They were not designed for this purpose. Northern Power Station closed in March last year.

Energy consumers in South Australia have been hit the hardest by high domestic gas prices because the state is relatively much more reliant on gas for its electricity generation than other NEM states. High gas prices translates to high electricity prices.

Without the state’s last coal fired generator, managing the SA grid became uncharted territory. The six blackouts experienced over the past two years were caused by a combination of extreme weather events and inexperience in managing this level of high intermittent generation. The Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) has subsequently put in a series of remedial measures to improve the reliability of the system. They are centred around ensuring there is more firm generation available within the state.

Given South Australia's energy systems are national: national energy and climate policy, national renewables targets, national electricity markets and national gas policy, the main solutions will need to be delivered at that level. So what can state governments really do?

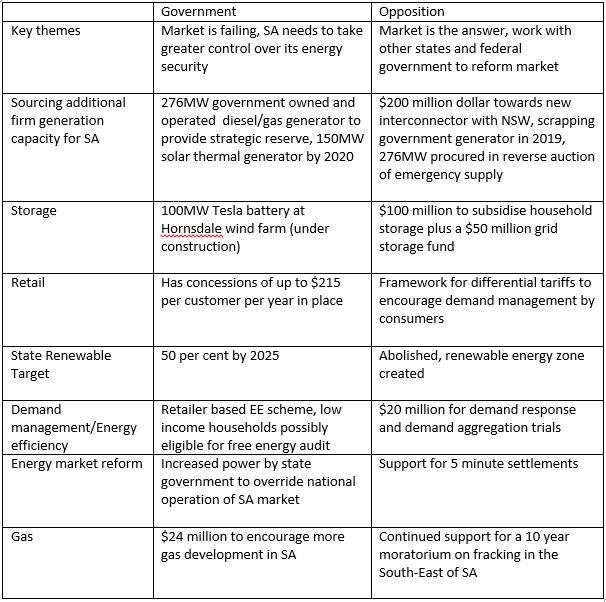

The Weatherill Government announced, and has since largely implemented its Our Energy Plan in March. This focussed around increasing the amount and viability of firm generation within the state: a new government built and owned power station to act as a strategic reserve, a new 100MW battery (being built by Tesla), a new 150MW solar thermal power station and measures to increase the viability of remaining firm generators within SA. They also increased gas exploration and development.

The main drawbacks of the SA Government plan are the level of government intervention, particularly in building and running a 230MW diesel/gas generator. The effect of this sort of government intervention tends to discourage businesses from investing in the SA market. First because it changes the expected returns and hence financial viability of a new generator, second because there is always the risk that future governments decide to put the asset into the market full time, and third because it signals the potential for further government intervention. It would have also been more useful if the 100MW of batteries subsidised by the government were spread across a wider cross section of technologies and applications and made more visible to the rest of the market. This would increase the “learning by doing” aspect of large scale battery deployment. But it wouldn’t have enabled the photo opportunities with Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla.

Liberal Energy Solution

This week the SA Opposition announced its energy plan. Unsurprisingly, it has ended up being almost the mirror opposite of the Weatherill Government’s Plan. The original headline claim is an average $302 a year saving by consumers on their energy bills (which appears both remarkably specific and ambitious).

The Opposition plan takes a contrary position to the Government plan on a number of key issues. Headline elements of the plan include:

- Support a national energy strategy and see the market as a part of the solution rather than part of the problem;

- Scrapping of the government owned and operated reserve generator and state renewable energy target;

- Sourcing extra generation via $200 million towards an interconnector to NSW and a reverse auction for private sector supply of the same amount of emergency generation;

- Subsidising installation of residential batteries by $100 million;

- No change to the Opposition’s proposed 10 year moratorium on gas development in the state’s south-east.

Comparison: SA Government vs Opposition Energy Plans

Discussion

From an industry perspective, like the Government plan, the Opposition energy plan is a mixed bag. Support for a national, market based approach to energy policy rather than “going it alone” is welcomed. So too is the switch to a competitive, market based procurement of emergency generation services. The need for emergency generation should only need to be temporary if and when national energy and climate policy can finally be agreed.

Abolition of the state’s RET also reflects the recommendations of the Finkel Review and the need to move away from both state and technology specific targets, although this is largely symbolic as the target has already been reached.

On the flipside subsidising an interconnector to NSW could do more harm than good, certainly in the absence of a national energy strategy. In the absence of any other supporting framework, this would enable NSW’s lower cost black coal generators to jump into the SA market and outbid the more expensive SA gas generators. It’s an expensive solution, which may deliver a short run easing of wholesale prices, but if it does it will also undermine the viability of the SA generators. It’s a variation of the same problem that resulted in the Northern Power Station closing ahead of schedule, sending prices skyrocketing and reducing reliability. New interconnection may be an important part of a national energy strategy, but we should develop the strategy first and see what we actually need.

Subsidising households to install new technology is not a new idea. It was first deployed to support rooftop solar PV systems. The problem is inefficiency and equity: it’s (politically) harder to get the new technologies into the right part of the grid, and the types of households who can afford and install a still expensive battery tend to be wealthier than all the other households who end up paying for their windfall gain. Storage should be deployed as and how it is most cost effective and delivers the greatest economic, not political benefit.

Increasing gas supplies into the east coast is an important measure to bring down gas prices. Moratoriums on gas development are not based on science and are unnecessarily heavy handed. Gas development is a crucial part of a more sustainable, affordable and reliable energy system and access to the resource requires more sophisticated thinking.

Conclusion

The challenges in South Australia reinforce the need for a national energy policy based on technologically-neutral and market-based solutions.

Electricity supply and investment is increasingly impacted by national policy settings, and policy inaction has resulted in driving uncertainty and costs. State governments have a role to facilitate the transformation, but escalated intervention tends to be politically rather than systemically driven.

Ironically, the best energy policy platform for SA is a combination of aspects of both the Government and opposition plans. A commitment to national and market solutions, temporary, contracted supply to meet short term supply needs, market led installation of technologies, an end to state and technology targets and access to more gas. Where technologies are enabled at scale (like batteries) the investment should be designed to maximise learning and deployment by the market.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.