Putting the squeeze on prices and competition

A new paper has found a drop in the spread of retail market offers following the re-introduction of price re-regulation in July last year.

The assessment[i] suggests that in trying to assist disengaged customers through a default market offer (DMO), policymakers have actually disadvantaged the majority of customers who shop around with the risk that over time fewer customers will see enough incentive to shop around.

It is echoed by findings from NSW’s Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal (IPART). In its recently released draft electricity retail market report,[ii] IPART expects the DMO to “have the effect of increasing the lowest market offers from what they otherwise would have been. The reduced spread in price means there is less to gain from switching and therefore being active in the market and retailers may increase their focus on non-price competition”.

Relative to June 2019, IPART found market offers in June this year fell for customers in the Ausgrid and Endeavour Energy distribution areas by 3.2 per cent and 2 per cent respectively, although they did increase slightly for those in the Essential Energy distribution area (0.8 per cent). IPART has flagged concerns that the DMO will lead to reduced competition and higher prices in the longer term.

How did we get here?

The DMO came into effect on 1 July 2019 in New South Wales, South East Queensland and South Australia with the offer price set by the Australian Energy Regulator (AER). At the same time, in Victoria the Essential Services Commission (ESC) introduced a similar effective price cap through the Victorian Default Offer (VDO). Both were designed as safety nets for disengaged customers.

The AER and ESC use different approaches to set the regulated price – the AER saw the DMO as a fall-back price and was designed to continue to encourage people to engage with the market. To achieve that it provided headroom to allow retailers to continue to differentiate their offerings and compete. In contrast the VDO did not include competitive headroom and was set much lower than the DMO.

Figure 1 below shows the timeline of deregulation of retail markets, including full contestability and when re-regulated prices were introduced. Victoria led the way in 2009 with the last jurisdiction in the NEM to deregulate electricity prices being South East Queensland in July 2016.

Figure 1: NEM deregulation timeline

Source: Energy Policy

At the time of the introduction of re-regulated prices last year, the Australian Energy Council and retailers argued that while price regulation would assist a small percentage of customers who did not shop around for better deals, it would potentially lead to perverse outcomes for the majority of retail customers who do engage. To address concerns for vulnerable and disengaged customers there were other mechanisms that could be used.

The Energy Policy paper highlights that a compression of offers is occurring leading to a reduction in the effective “return” on a search for the best deal of 2.3 per cent or around $37 a year on average.

The extent of the retail price gap between standing offers and market offers in markets following deregulation is shown in figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Comparison of Average Standing and Market Offers

Source: Energy Policy based on analysis of St Vincent de Paul and Alvis Consulting data

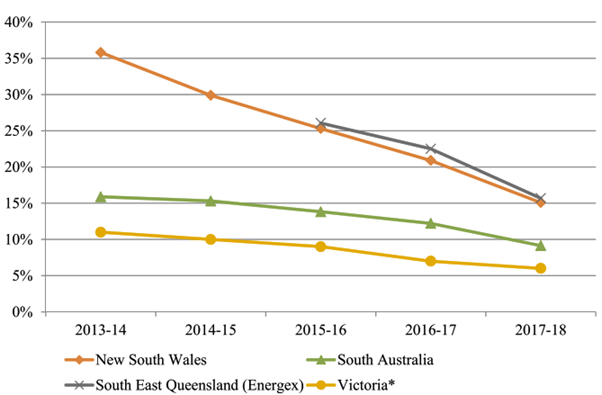

This price spread or dispersion increased after deregulation while the percentage of customers on standing offers fell over time where prices were deregulated (see figure 3).

Figure 3: Percentage of residential customers on standing offers

Source: Energy Policy

In jurisdictions with full retail contestability, regulated prices see a higher proportion of customers who stay on the standing offer. For example, there are more than 50 per cent of customers on standing offers in the ACT and more than 90 per cent in Tasmania, according to the paper.

In deregulated markets, the percentage of customers switching between retailers to get better deals are estimated to be between 20 and 30 per cent each year.

The paper highlights that introduction of price regulation has an impact on the number of customers who go into the market to find a better deal due to the risk that customers may perceive the returns from shopping around are reduced.

And the knock-on risk is that a drop in the numbers of customers switching ultimately will impact the level of competition.

So why introduce a price cap?

Policy makers see a regulated default price as a means to protect those customers who could face energy-related financial hardship.

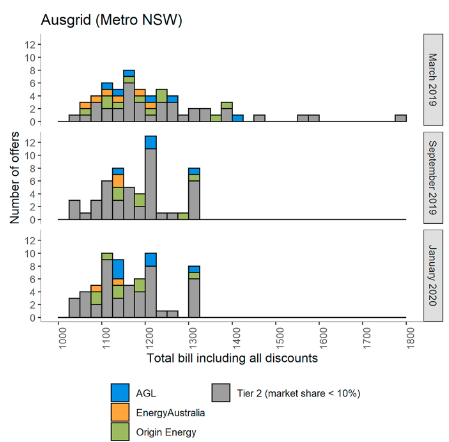

To assess the actual impacts the paper compares the retailer offers before and after the introduction of the DMO on 1 July 2019 and collected offers from the Australian Energy Regulator’s Energy Made Easy comparator website for March and September 2019 and then for January 2020 for Sydney (figure 4)

“After July 1, high price offers have disappeared from the market and there is a concentration of offers at the DMO price level. It also appears that the weight of the distribution has shifted to the right, with a greater number of offers in the range of $1100-$1200/year.”

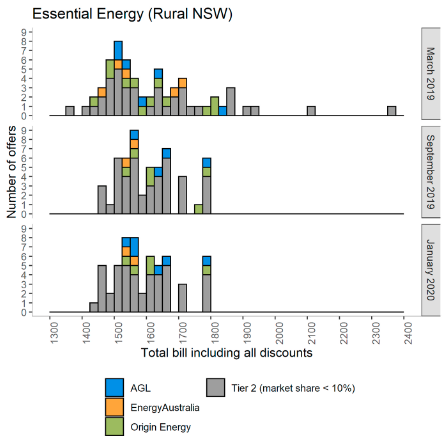

The paper finds following the DMO, Tier 1[iii] retailer offers concentrated in the middle of the bill distribution. There are still cheap offers from Tier 2 retailers, which may reflect changes in input costs. In rural NSW there is also evidence of compression of market offers (figure 5).

Figure 4: Comparison of bills distributions (Ausgrid area)

Figure 5: Comparison of bill distributions (Essential Energy area)

Source: Energy Policy

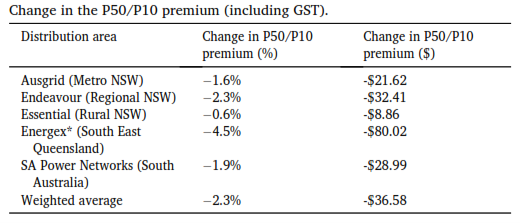

The comparison can be distorted because it does not account for changing retailer input costs, so the paper calculates a dispersion metric calculated as the percentage of the premium of the median market offer over the 10th percentile market offer in each distribution area. Using this metric, price dispersion reduced across all distribution areas between March 2019 and January 2020. Weighting the results by customer numbers showed a 2.3 per cent reduction in the premium of the median market offers over offers at the 10th percentile. Table 1 shows the variations with the largest change seen in South East Queensland and the smallest in rural NSW.

Table 1: Variation in premium

Source: Energy Policy

This metric found an overall reduction in the premium of the median market offer over an offer at the 10th percentile of 2.3 per cent or $37 a year on average.

Implications

The paper concludes that a retail price cap may lead to retailers withdrawing the cheapest offers. If customers are “sticky” and stay beyond the discounted benefit period profit maximising retailers have an incentive to aggressively compete by offering generous discounts for new customers, which is what we have seen in the deregulated markets.

When a price cap is introduced at a level below the profit maximising price for staying customers, the profitability of these customers is reduced and leads to a smaller discount for new customers. It results in a redistribution of consumer surplus from more active to less active customers.

Ironically, the drop in the premium market offer reduces the incentive to go looking for a better deal. “Policy makers should consider this reduced incentive with the dynamic efficiency gains that may be lost if customers are disengaged and not taking up new disruptive technologies that may lower system costs overall,” the paper argues.

Re-regulated prices leave customers on heavily discounted plans worse off with a redistribution from both vulnerable, but engaged and other engaged customers on low priced offers to disengaged customers on high standing offers.

The paper argues that price dispersion is “welfare enhancing” relative to price regulation with price regulation likely to be counter-productive.

Alternative approach

The challenge is to develop interventions that protect vulnerable and disengaged consumers while preserving the benefits for other consumers to remain active and engaged, particularly in an environment where new technologies may provide customers with new ways of reducing the costs of their energy consumption.

An alternative suggested in the paper is the creation of an auction for the right to serve vulnerable, disengaged consumers. It argues an auction could provide a way for entrant retailers to establish themselves in the market by giving them the opportunity to win a customer base. It would also shift responsibility of setting price caps away from the regulator, who may be under political pressure.

Under this approach, policymakers should determine an appropriate length of time for consumers to be on standing or high market offers (it suggests two years) and then after this period vulnerable customers would be automatically moved to a basic retailer offer determined through an auction for each distribution area. The auction would be annual and decided by the lowest proposed offer.

The argument is this would not reduce incentive to engage with the market. They have also suggested that policies such as requiring retailers to contact long standing customers on high price offers annually and directing them to the Energy Made Easy comparator website and letting them know they can make savings through switching could be useful mechanisms. Equally an expansion of state-based concession schemes would assist the most vulnerable customers.

Overall, the paper concludes that price caps are too blunt an instrument for dealing with vulnerable, disengaged customers given the potential to harm other customers (including the vulnerable customers who are engaged) and damage competition. Its modelling shows there has already been a drop in the incentive to go to the market for customers.

[i] The impacts of price regulation on price dispersion in Australia’s retail electricity markets, Ryan Esplin, Ben Davis, Alan Rai, Tim Nelson, Energy Policy.

[ii] https://www.ipart.nsw.gov.au/files/sharedassets/website/shared-files/investigation-compliance-monitoring-energy-publications-monitoring-the-retail-energy-markets-during-201920/draft-report-monitoring-the-electricity-retail-market-2019-2020.pdf

[iii] Tier 1 retailers are defined as those with a market share of more than 10 per cent. Tier 2 have a market share below 10 per cent.

Related Analysis

Beyond the “loyalty penalty”: unlocking CER value is the real pathway to a services market

The Australian Energy Market Commission pricing review has sparked debate about fairness and competition, with the AEC cautioning against treating price differentials as the core problem. Recent evidence from the ACCC suggests competition and recent reforms are improving customer outcomes with the AEC arguing that a true shift to a services-based market will depend on unlocking and fairly sharing CER value, not weakening the competitive dynamics that drive innovation. We outline our position on the review. Read more.

A New Year: New regulated offer; new records but some old challenges

A new year has brought major developments across Australia’s energy markets, with new regulatory interventions alongside record-breaking renewable generation. The Federal Government’s Solar Sharer Offer marks a significant shift in retail market design, while the wholesale market delivered historic renewable output and much lower prices, driven largely by strong wind and growing battery capacity. We take a look at what these changes mean for customers, retailers and the reliability of the power system, and where old challenges continue to resurface.

2025 Another Year Full of Energy (Developments)

2025 has been another year in which energy-related issues have been front and centre. It ended with a flurry of announcements and releases, including a new Solar Sharer tariff proposed by the Federal Government and the release of the 2026 Integrated System Plan (ISP) draft. Below we highlight some of the more notable developments over the past 12 months.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.