Metering: Measuring the benefits of competition

Victoria was the first Australian state to implement a mandated smart meter rollout which highlighted to other jurisdictions the high costs and customer backlash associated with that approach. Not surprisingly, other state governments, along with the Federal Government, took these Victorian learnings and opted to design a new national regulation to boost competition among meter service providers in future and pursue a market-led approach that will come into effect in December this year.

The exception will be Victoria. Given Victoria’s strong track record in metering innovation (under a previous Labor government), it was interesting to see the Victorian Government opting out of the metering competition reforms last week, and delaying any decision that would open up competitive metering of electricity in households until 2021.

The Victorian outcome creates a two tier regulatory system for retailers who have customers in multiple jurisdictions, which is most of them. Simply, it means that retailers will incur substantial extra costs for running different operating and compliance processes for metering in Victoria. It also denies Victorians the benefit of competitively priced metering and access to metering-related services. It effectively locks in higher metering costs in Victoria at a time when the Victorian and Federal governments have flagged their concerns about higher power prices and are inquiring into what is driving higher prices.

New Zealand: Metering competition

To understand why the other states and the Australian government rejected the mandated smart meter rollout - given that smart meters are an enabling tool for new technologies and electricity management - we need to look across the ditch to the Land of the Long White Cloud. That’s because New Zealand has made significant progress and nearly completed a national smart meter rollout without mandated installation.

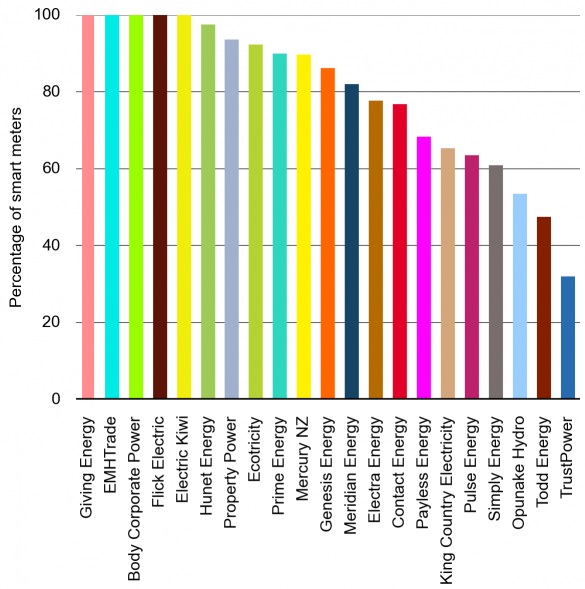

More than 70 per cent of New Zealand electricity connections now have smart meters. New Zealand’s Electricity Authority highlights that an increasing number of electricity retailers are exploiting the technology to deliver new customer services[i]. Figure 1 below shows that more than half of the electricity retailers in New Zealand have more than 80 per cent of their customers with smart meters. New entrant retailers in New Zealand have 100 per cent smart meters installed as they only accept customers with smart meters. Retailers have built their business models on using smart meter data to reduce costs, increase efficiency, improve customer service and offer new services and tariffs.[ii] This is helping drive the uptake of the meters.

Figure 1: Percentage of customers with installed smart meters – New Zealand

Source: Electricity Authority New Zealand, 2016

Metering competition in New Zealand has resulted in new entrants in its electricity market over the past two years building their product offerings on the foundation of smart meter technology. This has created new choices for consumers and further enhanced retail competition.

Competition between retailers underpins the incentives that individual retailers have to roll-out smart meters to their customers because it allows them to deliver a broader range of services and products for customers. A market-driven rollout also ensures that the meter specifications can be based on the smart metering services that customers want. It provides greater flexibility for retailers to develop new products and services for their customers. Victoria’s mandated smart meter rollout has failed to harness these competitive dynamics because it has led to a one-size-fits-all approach.

Electricity retailers in New Zealand provide households with more control over their electricity use with a range of offerings from in-home displays, online tools and apps, through to integration with solar installers and full cost disclosure with access to spot market-based pricing. Victoria’s mandated smart meter rollout has widely failed to deliver these consumer outcomes.

If New Zealand can do it why can’t Australia?

In Australia, the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) made its final determination on the Expanding Competition in Metering and Related Services Rule Change in November 2015[iii]. The AEMC final determination provides the framework for a market-led rollout of smart meters, and outlines which parties have responsibility for various aspects of metering. In Australia, as in New Zealand, retailers are well placed to enable a market-driven delivery of smart metering to customers. Competition amongst retailers to offer services paired to the metering addresses consumers’ legitimate cost versus benefit concerns that arose in Victoria. It satisfies the what’s-in-it-for-me question that plagued the Victorian mandated approach. It is a prerequisite to help avoid the customer backlash seen in that state.

The change in metering competition rules announced by the AEMC means that Australian (except Victorian) retailers can rollout smart meter products better suited to consumer demand. By definition, the market-driven rollout occurs in response to consumers wanting to have their meters upgraded so they can access products that can bring cost benefits and that are better tailored to their lifestyle and energy use patterns. Under the AEMC determination consumers do not have to change their existing meters unless they agree to do so (although some meters may be replaced for maintenance reasons)[iv].

Typical amongst the new offers available, most retailers in Australia are now offering packages that not only incorporate the installation of solar photovoltaic and storage batteries, and a web-based smart energy platform that communicates with and via the smart meter. With Victoria opting out of metering competition until at least 2021, Victorians are likely to have to wait for those benefits.

NSW has taken the path of metering competition

Power remains firmly in the hands of NSW customers as it is they who will decide whether the benefits of a smart meter meets their needs before their meter is updated. Under the NSW Government market-driven smart meter rollout, there will be a variety of retailer led options to choose from, and if New Zealand is any guide a broader range of products available off the smart meter platform. The retailer will consider the competitive response of its rivals and the response of its customers. Driven by competition, retailers seek to provide the meter at least cost to the consumer. The driver in this case is the need for the retailer to maximise customer value or risk losing them. This is in contrast to a regulated distributor led model, where retail products are not the main consideration.

In NSW the transition to new metering technologies will be challenging and not without cost. The New Zealand experience though highlights that it is possible to have competitive market arrangements and business cases that meet consumer expectations at the same time. Greater competition incentivises service providers in NSW to focus on improving services to their customers because that will help differentiate them from other providers.

Extra costs without metering competition

As a result of the Victorian Government’s decision, most retailers who have customers in multiple jurisdiction will incur substantial extra costs to set up different processes. The divergence in metering arrangements between Victorian and other states is likely to be so great that retailer will need to look at running separate systems, processes and increasing resources to manage them.

Victorian distributors have highlighted that there are additional functionalities in the Victorian minimum services specification (VMSS) meters compared to the national minimum services specification. However, the Victorian Department has not made it clear what technologies are actually available, nor whether all the additional functionalities of the Victorian AMI meter are actually in use. Notwithstanding, the national framework can cater for certain capabilities of the Victorian metering specification if they were displaced. An important difference is that in Victoria retailers cannot control what the smart meter does and are dependent on the meter owner.

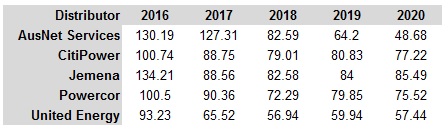

Bringing down Victorian metering charges is partly influencing the delay in introducing metering competition for Victoria. Whilst regulated metering charges in Victoria have been falling since 2014, they are still at a materially high level, as the table below shows.

Table 1: Annual metering charge, $/household customer

Source: Australian Energy Regulator, 2016

Although a different type of meter to Victoria’s the metering charges for national minimum services specification (NMSS) smart meters in NSW are lower than those in Victoria. The example for Ausgrid below shows that the annual metering charge for household customers is lower than the annual metering charge from Victorian distributors in 2016[v] - followed by future annual metering charges which are much lower than any of Victoria’s charges.

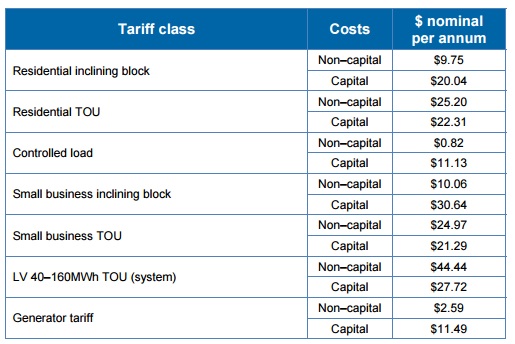

Table 2: Annual metering charges for FY16 by Tariff

Source: Ausgrid, 2015

Where metering has been opened to competition, such as in NSW, it has given retailers the ability and incentive to manage this element of the cost stack. At the same time they are able to differentiate themselves through the capabilities of the meter. While the NSW process has only just started, making it difficult to be definitive, the New Zealand experience does give cause for optimism when considering the benefits.

Retailers can meet the safety requirements

Safety must be a primary concern and it was raised as an issue during the Victorian smart meter rollout. There are current (and unfortunately inconsistent) state regulatory regimes that metering providers need to be competent in and comply with to ensure minimum safety standards are maintained.

The Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) also undertakes ongoing six monthly audits of Meter Provider requirements. The Meter Provider must submit the names, licenses of its technicians and training schedule and training material to AEMO for review and approval. Certified electricians must undertake further training as part of the Meter Provider AEMO accreditation process. This includes jurisdictional safety and compliance training which is then also reviewed and approved by AEMO.

In a competitive metering environment this does not change. Anyone who wants to be a meter provider will continue to need to meet AEMO’s requirements as well as comply with state-based safety requirements. This would apply for retailers as well. As electrical safety moves beyond the domain of the DNSP – which it does with PV, batteries etc as well as metering, the case for a nationally harmonized electrical safety regime becomes ever stronger.

Decision rewards Distributors

The Victorian Government’s decision to defer may have been driven by a desire to monitor the implementation of metering competition in other jurisdictions. Given the state has already been through a mandated meter rollout and the resultant consumer backlash, damning audit reports about the level of benefits to Victorian households from their smart meters and the distributor asset value benefit, it seems rather late in the day to take a wait and see approach.

In the meantime all consumers are paying to manage different compliance and regulatory regimes, while Victorian consumers will miss out on many of the benefits that smart metering can deliver. Look no further than New Zealand.

[i] Electricity Authority New Zealand, “20 September 2016 - Businesses getting smart with smart meters”, < https://www.ea.govt.nz/about-us/media-and-publications/media-releases/2016/20sep16/ >

[ii] ibid

[iii] AEMC, 2015, “Expanding competition in metering and related services”, <

[iv] Ibid [v] Ausgrid, 2015, “Initial Pricing Proposal For the Financial Year ending June 2016”, << http://www.aer.gov.au/system/files/Initial%20Pricing%20Proposal%20-%20Main%20Submission.pdf >>, p37

Related Analysis

The return of Trump: What does it mean for Australia’s 2035 target?

Donald Trump’s decisive election win has given him a mandate to enact sweeping policy changes, including in the energy sector, potentially altering the US’s energy landscape. His proposals, which include halting offshore wind projects, withdrawing the US from the Paris Climate Agreement and dismantling the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), could have a knock-on effect across the globe, as countries try to navigate a path towards net zero. So, what are his policies, and what do they mean for Australia’s own emission reduction targets? We take a look.

UK looks to revitalise its offshore wind sector

Last year, the UK’s offshore wind ambitions were setback when its renewable auction – Allocation Round 5 or AR5 – failed to attract any new offshore projects, a first for what had been a successful Contracts for Difference scheme. Now the UK Government has boosted the strike price for its current auction and boosted the overall budget for offshore projects. Will it succeed? We take a look.

Energy transition understanding limited: Surveys

Since Graham Richardson first proposed a 20 per cent reduction in Australia’s greenhouse gas emission levels in 1988, climate change and Australia’s energy transition has been at the forefront of government policies and commitments. However, despite more than three decades of climate action and debate in Australia, and energy policy taking centre stage in the political arena over the last decade, a reporting has found confusion and hesitation towards the transition is common among voters. We took a closer look.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.