Mandatory electricity code: ‘Sparking’ up the wrong tree

On 23 February, the Federal Government announced that it would impose a mandatory industry code on electricity retailers, known as the Electricity Retail Code. This Code has been driven by the Federal Government’s desire to demonstrate that it can remedy high power bills. It hopes that the effect of this Code, to introduce a Default Market Offer (DMO), will reduce energy prices for consumers without stifling competition and the market offers that the majority of households are on.

So will the industry code work and is re-regulation the best way to keep a lid on electricity prices?

What is an industry code?

Industry codes are governed by Part IVB of the Competition and Consumer Act (CCA). They are intended to set out the rules that regulate the behavior of industry participants towards other industry actors and/or customers. The code can be either voluntary or mandatory. Mandatory codes are quite rare though they do exist in certain sectors, such as franchising and horticulture. Section 51AE of the CCA grants the Government the power to prescribe a mandatory industry code, but does not regulate the process Government must follow when exercising this power. Instead, it is expected the process will respect the principles laid out in two Government guidelines: Australian Government Guide to Regulation (the ‘Government Guideline’) and Industry Codes of Conduct Policy Framework (the ‘Treasury Guideline’).

Combined, the Government Guideline and the Treasury Guideline make up 89 pages and their central theme is crystal clear: extensive public consultation is indispensable for getting regulation right. To satisfy this, the guidelines lay out a number of expectations of Government. These include ensuring all affected stakeholders have been consulted in a “genuine and timely way”;[1] publishing a Regulatory Impact Statement that invites debate about the potential impact of the proposed regulations;[2] and making sure that all alternative regulatory options have been properly considered.[3] So how then does the proposed Electricity Retail Code fare in relation to these principles?

The birth of the Electricity Retail Code: Reasonable or rash?

Regulation of electricity prices was a key recommendation of the ACCC Report, and in October 2018 the Government indicated that it would progress a DMO along the lines proposed by the ACCC. Ideally that would have been achieved with the assistance of the States, which generally control retail electricity pricing. However, the COAG Energy Council was not inclined to support a Federal takeover of retail electricity prices and so, on 15 February 2019, the Government confirmed its intention to introduce a DMO via an industry code under the CCA. This was contrary to the wishes of the States.

The new Code will apply in New South Wales, South Australia and Southeast Queensland. Victoria was excluded because it had recently announced its intention to implement a Victorian Default Offer. The Government published an Exposure Draft of the Code on 23 February and opened it for public consultation until 12 March. It also set an implementation date of 1 July 2019.

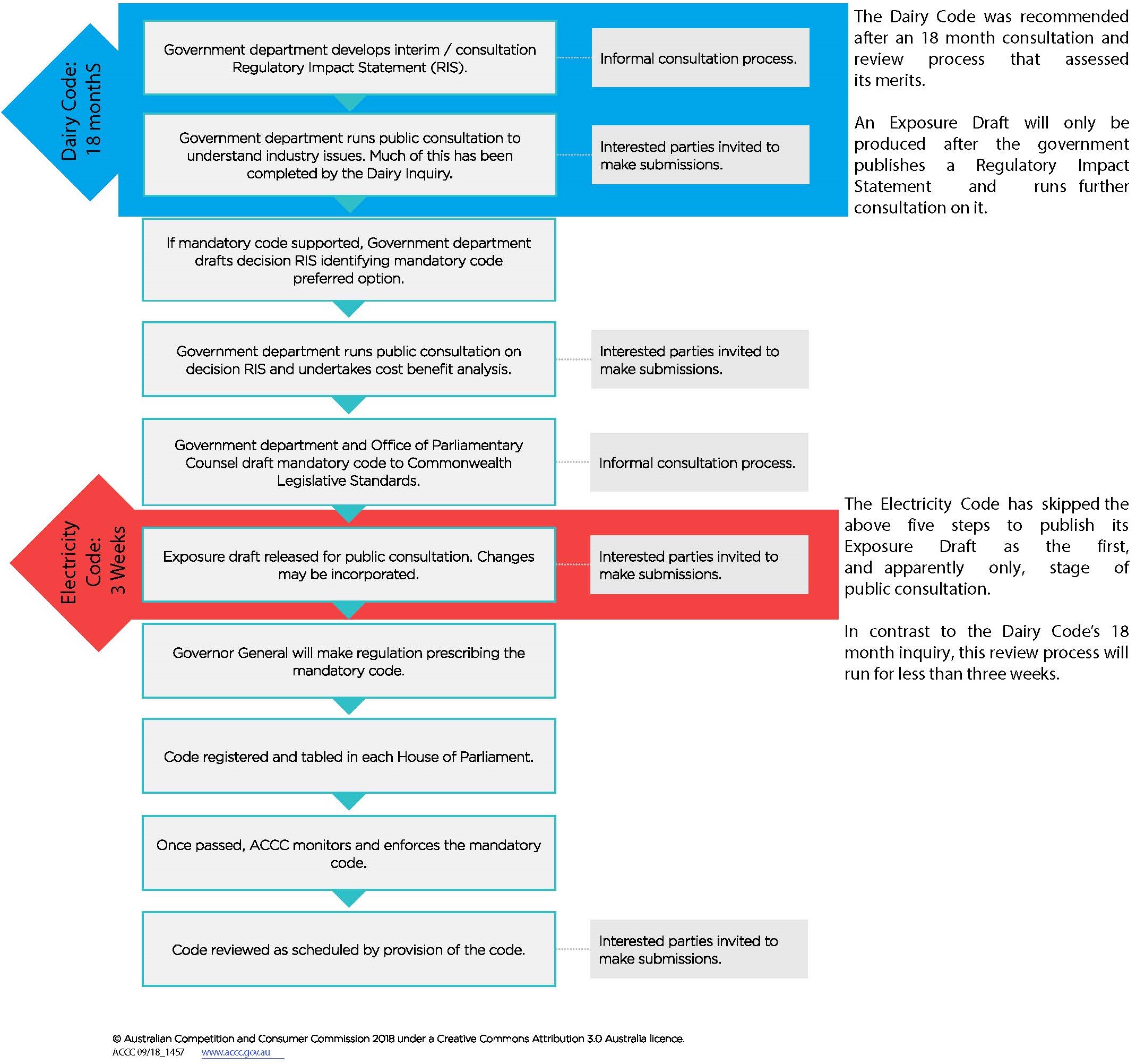

The sudden pursuit of the Electricity Retail Code represents a significant departure from the considered processes that underpinned earlier mandatory codes. Usually, mandatory codes are borne out of a comprehensive review into the respective industry, which can take between 18 to 24 months. During this time, all affected stakeholders are invited for consultation and their submissions help determine the merits of introducing a code. In this instance, the consultation period is markedly short (less than three weeks), placing it well below the 30 to 60 day period of consultation suggested in the Government’s own Government Guideline.[4] Moreover, no review into the merits of a mandatory code for retail electricity has taken place.[5] These discrepancies are highlighted in Figure 1, which contrasts the process leading up to the Electricity Retail Code with that of the proposed Dairy Code.

Figure 1: ACCC process for developing a mandatory code

The hastiness of this consultation period is exacerbated by the Code being a Government, rather than industry, initiative. Previous mandatory codes, such as those in the franchising and horticulture sector, were borne out of industry attempts at self-regulation. This is in line with the Treasury Guideline, which states that industry-led initiatives should be the ‘preferred method of addressing specific problems in an industry’ presumably because of better technical knowledge.[6]

The Electricity Code further departs from its predecessors by restricting what the consultation can be about. The Treasury Guideline makes it quite clear that Government should first ‘initiate a public consultation process to assess the merits of prescribing a code’.[7] Here, however, submissions were expected to only focus on the content of the Code, not the actual merits of having one. This approach has hampered any discussion about viable alternatives to a code. Instead, the Electricity Code appears to do exactly what the Government Guideline explicitly says is not acceptable: ”presenting one fait accomplis option”.[8] Considering that the Government has already announced its implementation date, it appears a foregone conclusion that the Code will be implemented regardless of any advice to the contrary.

But don’t good outcomes outweigh poor process?

If good consumer outcomes are guaranteed from having the Electricity Retail Code then surely these procedural pitfalls can be overlooked, or at the very least, addressed later on. Unfortunately, any meaningful discussion about consumer outcomes has been lost because the Government has to date declined to produce a Regulatory Impact Statement. This is problematic since there have been very genuine concerns expressed by the Government’s own rule maker – the Australian Energy Market Commission - that a DMO will not benefit consumers overall and might even concentrate power into the hands of the largest energy retailers. Customers are likely to see the DMO as representing the cheapest offer, when it in fact this will not be the case. If the UK experience with a DMO is any guide, price regulation actually makes it harder for smaller retailers to compete and deters new market entrants, to the detriment of consumers.

The importance of proper consultation to protect against unintended consequences is further justified by the irregular reach of the Electricity Code. Since mandatory industry codes are a Commonwealth initiative, they usually apply nationwide. The Treasury Guideline clarifies this expectation, emphasising that there should be a compelling “national public interest” for prescribing a code.[9] All existing mandatory codes are nationwide in scope, which is not just necessary for uniformity, but also to ensure costs can be kept to a minimum and not passed on to non-participating jurisdictions. The fact that the Electricity Code only applies to two states and the south-east corner of a third is likely to produce some unknown outcomes when the DMO is introduced into the market. Having a proper risk assessment may have helped fleshed out some of these unknowns and allowed regulators and retailers to protect against them.

Conclusion

The Electricity Retail Code represents a significant reform with significant consequences. As such, it is worthy of a thorough consultation process. The Government’s omission of any meaningful discussion may satisfy political needs but risks the DMO producing adverse outcomes for retailers and consumers alike that are likely to need redress in the future. While some large retailers might be able to absorb these changes, consumers are likely to be left confused and worse off.

[1] Australian Government, Australian Government Guide to Regulation, March 2014, p2.

[2] Treasury, Industry Codes of Conduct – Policy Framework, November 2017, p12.

[3] Australian Government, Australian Government Guide to Regulation, March 2014, p26.

[4] Australian Government, Australian Government Guide to Regulation, March 2014, p45.

[5] While there was recently a review into the energy industry, it did not entertain the idea of an Electricity Code and therefore there was no previous consultation assessing its merit or content.

[6] Treasury, Industry Codes of Conduct – Policy Framework, November 2017, p2.

[7] Treasury, Industry Codes of Conduct – Policy Framework, November 2017, p14.

[8] Australian Government, Australian Government Guide to Regulation, March 2014, p26.

[9] Treasury, Industry Codes of Conduct – Policy Framework, November 2017, p11.

Related Analysis

A New Year: New regulated offer; new records but some old challenges

A new year has brought major developments across Australia’s energy markets, with new regulatory interventions alongside record-breaking renewable generation. The Federal Government’s Solar Sharer Offer marks a significant shift in retail market design, while the wholesale market delivered historic renewable output and much lower prices, driven largely by strong wind and growing battery capacity. We take a look at what these changes mean for customers, retailers and the reliability of the power system, and where old challenges continue to resurface.

2025 Another Year Full of Energy (Developments)

2025 has been another year in which energy-related issues have been front and centre. It ended with a flurry of announcements and releases, including a new Solar Sharer tariff proposed by the Federal Government and the release of the 2026 Integrated System Plan (ISP) draft. Below we highlight some of the more notable developments over the past 12 months.

Getting it right: How to make the “Solar Sharer” work for everyone

On paper, the government’s proposed "Solar Sharer Offer" (SSO) sounds like the kind of policy win that everyone should cheer for. The pitch is delightful: Australia has too much solar power in the middle of the day; the grid is literally overflowing with sunshine: let’s give households free energy during 11am and 2pm. But as the economist Milton Friedman famously warned, "There is no such thing as a free lunch." Here is a no-nonsense guide to making the SSO work.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.