Investment worries: The IEA’s latest assessment

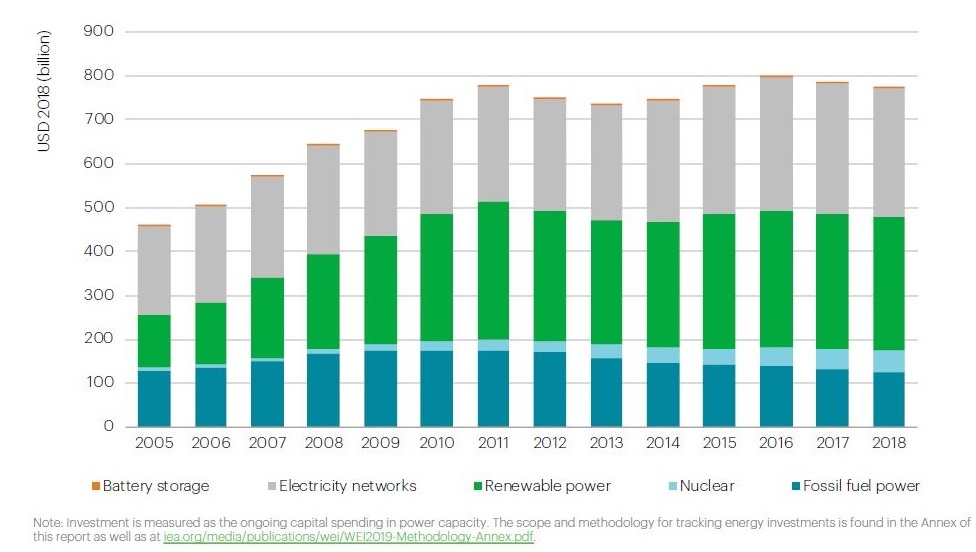

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has released its assessment of world energy investments which shows that global power sector investment fell 1 per cent to just over USD 775 billion in 2018, with lower capital spending on generation (see figure 1). Investment in networks also edged down, but investment in battery storage jumped 45 per cent (although this is from a low base).

Figure 1: Global investment in the power sector by technology

Source: IEA World Energy Investment 2019

Source: IEA World Energy Investment 2019

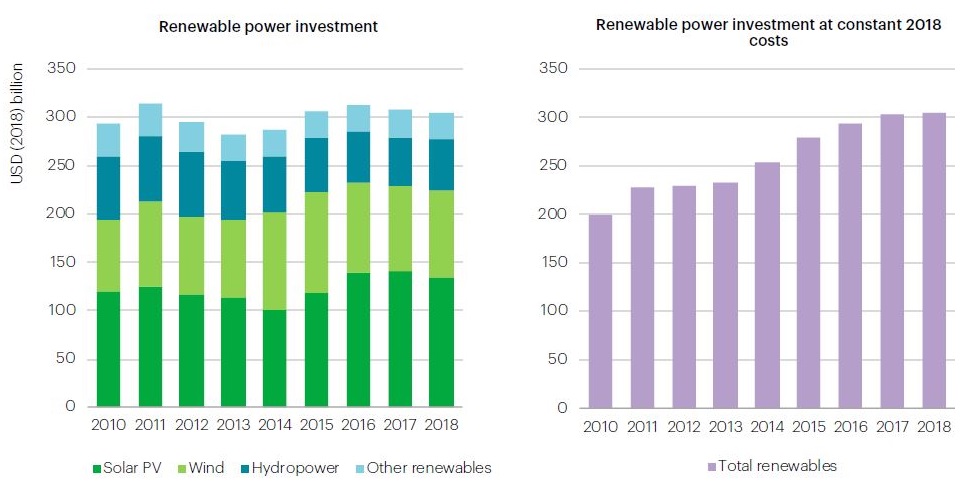

Investment in renewables globally fell 1 per cent in 2018, while investment in coal-fired generation declined by almost 3 per cent (its lowest level since 2004). Net additions to renewable capacity were flat and costs fell in some technologies with a dollar of renewables buying more capacity today than previously, the IEA reports. If the investment spending over time is adjusted to 2018 cost levels, renewables investment is up 55 per cent in the past eight years (figure 2). On this cost-adjusted basis, investment was strongest in solar PV and wind, which benefitted the most from falling costs and higher deployment.

Figure 2: Investment in renewable power actual spending vs investment at constant 2018 cost levels

Source: IEA analysis with calculations for solar PV, wind, and hydropower based on costs from IRENA (2019).

Source: IEA analysis with calculations for solar PV, wind, and hydropower based on costs from IRENA (2019).

Unadjusted solar PV spending fell around 4 per cent, while wind investment was flat in 2018. The drop in solar investment was largely due to policy changes in China, while in India solar spending was higher than coal-fired power stations. Total renewable spending in India topped its investment in fossil fuel based generation for a third year running and was helped by government tendering and uncertain financial prospects for new coal power plants, according to the report.

Interestingly, investment in solar PV and wind in the US was up 15 per cent, helped along by corporate procurement.

Renewables in Europe accounted for 75 per cent of generation spending in 2018. While wind farm projects declined in Europe, they remained the dominant source and offshore wind farms accounted for about half of all wind investment.

Coal Investment

The 3 per cent drop in coal investments (less than USD 60 billion and the lowest level this century) was mainly driven by lower investment in China and India. There was also an increase in coal plant retirements, and yet the world’s coal power fleet continued to grow due to additions in developing Asian countries. Southeast Asia, China and India accounted for the bulk of the new coal-fired generation (see figure 3).

The Middle East and North African (MENA) and Southeast Asian regions were the main drivers of fossil fuel investment, where it was higher than for renewables. In the past five years MENA power sector spending has risen by almost 40 per cent, while in Southeast Asia it has remained flat.

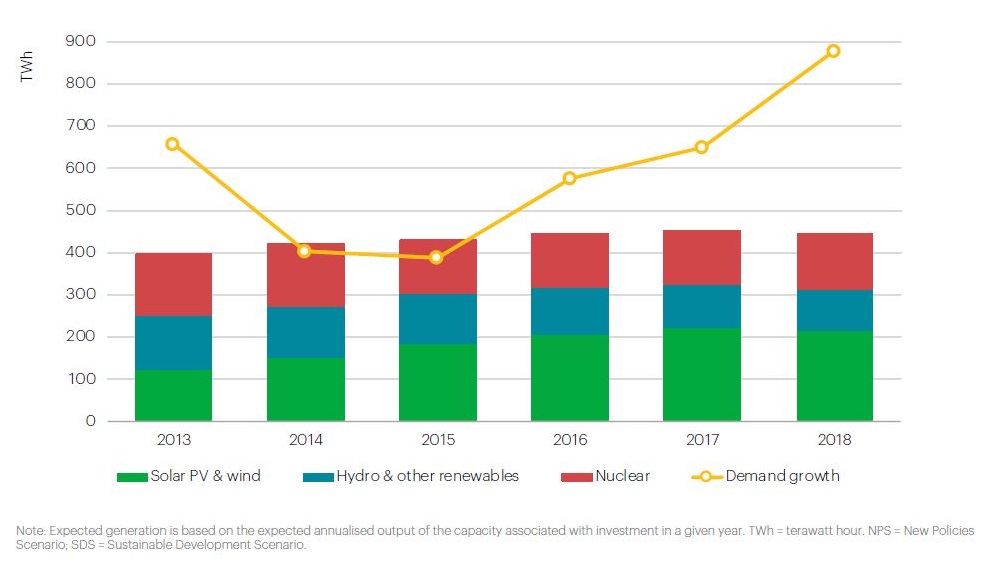

The IEA flags that the continuing investment in long-lived coal plants appeared to be aimed at filling a growing gap between rising demand and a levelling off of expected generation from low-carbon investments (renewables and nuclear). It warns that without carbon capture technology or incentives for earlier retirements, coal power and its high carbon emissions will stay part of the global energy system for many years to come.

Figure 3: Power sector investment by major countries and regions, 2018

Source: IEA World Energy Investment 2019. Note: MENA = Middle East and North Africa; SSA = sub-Saharan Africa; Other RE = (bioenergy, geothermal, solar thermal electricity, and marine).

Source: IEA World Energy Investment 2019. Note: MENA = Middle East and North Africa; SSA = sub-Saharan Africa; Other RE = (bioenergy, geothermal, solar thermal electricity, and marine).

After rising to their record level in 2012, spending on gas-fired power plants slowed in 2018, led by the Middle East and North African region and in the US (which has had a large pipeline of gas projects finalised in recent years).

Meanwhile, final investment decisions on new power stations declined to their lowest level this century and retirements were at near record levels. Global investment in electricity grids was slightly down (1 per cent), largely because of lower spending on distribution, while transmission continued to grow.

Investment in battery storage jumped 45 per cent to a record of more than USD 4 billion with strong increases in both grid-scale and batteries for home storage, which were the majority of installations. The overall investments in battery storage, however, was equivalent in dollar terms to just over 1 per cent of total grid spending.

One trend highlighted by the IEA’s work is that the output from low carbon power generation is not keeping pace with the growth in demand (figure 4).

Figure 4: Expected generation from low carbon power investments compared to electricity demand growth

Source: IEA World Energy Investment 2019

Source: IEA World Energy Investment 2019

The IEA reports that investment in low-carbon energy – both in supply and demand – was relatively stable at around USD 620 billion in 2018. But spending growth has stagnated in the past two years, compared with 3 per cent growth in 2016. The share of low-carbon in total energy investment stayed at around 35 per cent in 2018.

Low-carbon spending in 2018 was marked by unchanged investment in energy efficiency and nuclear, while spending on renewables nudged down.

The IEA report signalled a growing “mismatch between current trends and the paths to meeting the Paris Agreement and other sustainable development goals”.

Related Analysis

International Energy Summit: The State of the Global Energy Transition

Australian Energy Council CEO Louisa Kinnear and the Energy Networks Australia CEO and Chair, Dom van den Berg and John Cleland recently attended the International Electricity Summit. Held every 18 months, the Summit brings together leaders from across the globe to share updates on energy markets around the world and the opportunities and challenges being faced as the world collectively transitions to net zero. We take a look at what was discussed.

Great British Energy – The UK’s new state-owned energy company

Last week’s UK election saw the Labour Party return to government after 14 years in opposition. Their emphatic win – the largest majority in a quarter of a century - delivered a mandate to implement their party manifesto, including a promise to set up Great British Energy (GB Energy), a publicly-owned and independently-run energy company which aims to deliver cheaper energy bills and cleaner power. So what is GB Energy and how will it work? We take a closer look.

Delivering on the ISP – risks and opportunities for future iterations

AEMO’s Integrated System Plan (ISP) maps an optimal development path (ODP) for generation, storage and network investments to hit the country’s net zero by 2050 target. It is predicated on a range of Federal and state government policy settings and reforms and on a range of scenarios succeeding. As with all modelling exercises, the ISP is based on a range of inputs and assumptions, all of which can, and do, change. AEMO itself has highlighted several risks. We take a look.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.