Industry super and nuclear power: Compare the pair

Industry Super Australia recently published a discussion paper, Modernising Electricity Sectors – A guide to long-run investment decisions (the ISA Report).[i] Controversially it proposed investigating nuclear power to replace retiring coal plant. What’s the report about, and do its findings stack up? We take a look.

Written by two economists, the paper deals with the uncertainties facing the Australian electricity sector, in the face of increasing urgency to reduce emissions. It characterises the two scenarios available to investors as:

- Long-term solutions – anticipating future government decisions, making strategic investments to fill gaps in networks and replacing existing fossil fuel generation with alternative technologies.; or

- Business-as-usual – capitalising on price movements in electricity markets and/or to maximise public subsidies paid to participants.

It then goes on to make a number of recommendations to facilitate the long-term solutions, including:

- long-term technologically-neutral policy certainty;

- more market planning and more competition;

- long-term supply contracts underwritten by governments;

- establishment of an independent expert panel;

- establishment of a public authority for transmission and distribution planning; and

- setting emissions targets as high as possible.

Discussion

The goal of the paper is zero emissions electricity, with consideration of the security and reliability of supply, given the inherently variable nature of renewable energy’s fuel sources.

To determine the different technologies’ costs, the paper considers:

- “plant costs” – construction costs and shallow connection costs, represented by levelised costs of energy (LCOE); and

- “grid costs” – additional infrastructure for system stabilising and frequency & voltage control, and energy security costs.[ii]

The paper uses three different sources for LCOE costs, being Lazard,[iii] OECD,[iv] and the Energy Information Reform Project.[v] While these are useful sources for US data, it would have been more appropriate to use Australian data, as published by the CSIRO in its GenCost 2018 Report.[vi]

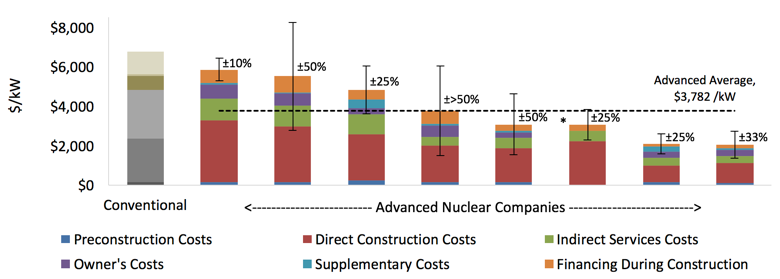

An example is the use of nuclear capital costs. Here is the chart from the Energy Information Reform Project, which reports average costs of US$3,782/kW (about A$5,400/kW):

Figure 1: Nuclear Capital Cost Results (US$)

Source: Energy Information Reform Project, Figure 4, p.10

Source: Energy Information Reform Project, Figure 4, p.10

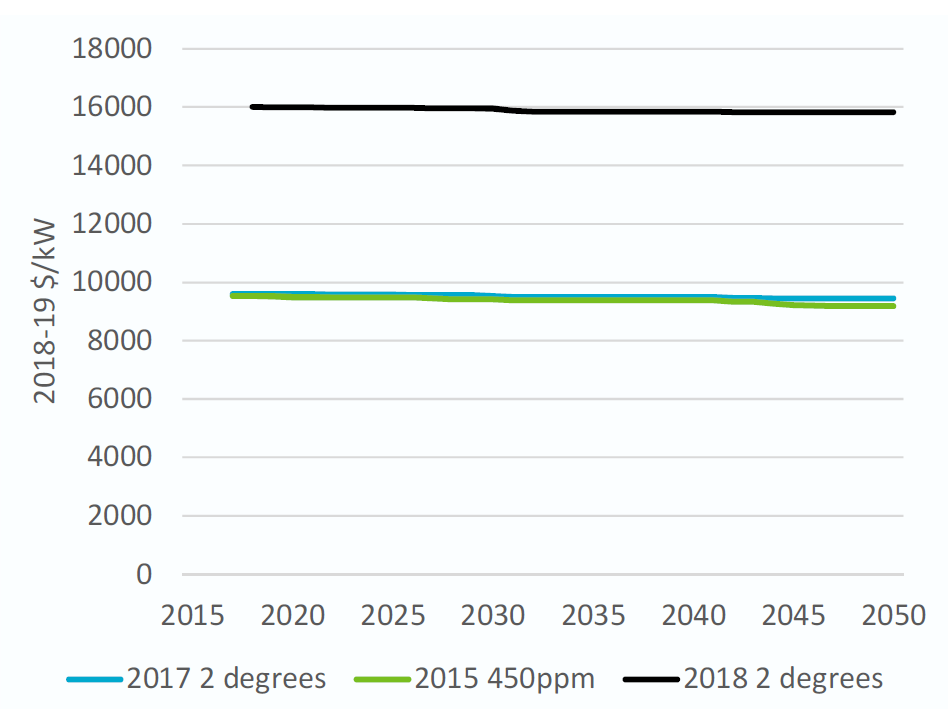

In contrast, here is a CSIRO graph showing prices of about A$10,000/kW for large-scale nuclear, and A$16,000/kW for small-scale nuclear:

Figure 2: Projected capital costs for small (2018 projections) and large scale nuclear from 2015 and 2017 projections (A$)

Source: CSIRO, Figure 3-9, p.16

Source: CSIRO, Figure 3-9, p.16

While the figures are not directly comparable, it is clear that the Australian figures are significantly different from the US sources cited, this then puts much of the subsequent analysis into conflict with conventional Australian analyses that conclude that nuclear is an economically unrealistic technology.

Capacities and costs

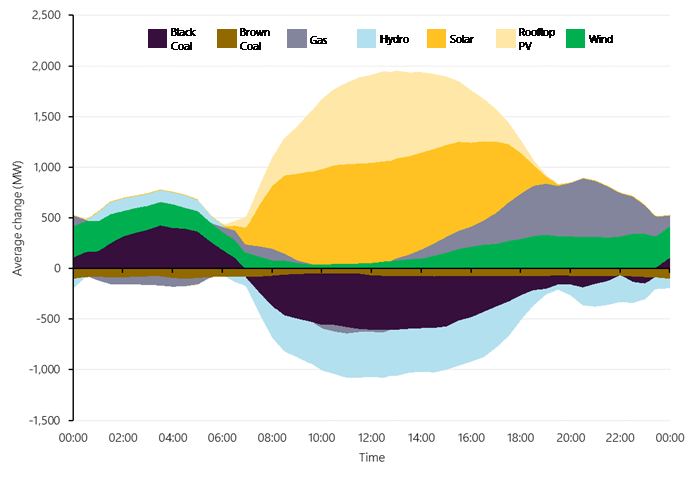

The ISA Report is quite rightly concerned about the “Duck Curve”. Again, not needing to refer to US sources, AEMO’s QED Report provides a good example of what is already occurring in Australia.[vii]

Figure 3: Change in Supply – Q1 2019 versus Q1 2018 by time of day

Source: AEMO, Figure 10, p.11

Source: AEMO, Figure 10, p.11

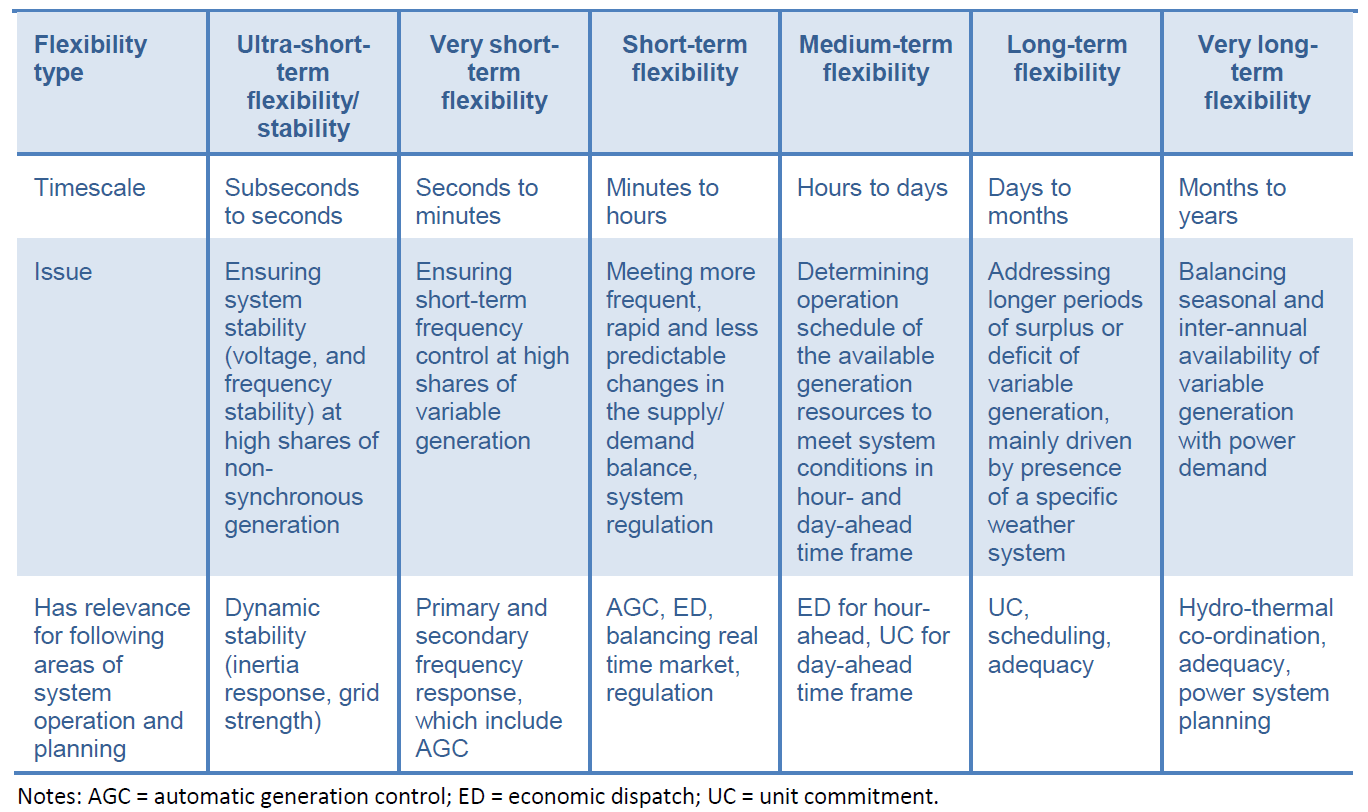

This shows that due to the penetration of domestic solar, grid demand during the day is declining markedly. Thus, we need plant that is responsive to short-term variations, but is also dependable over the longer-term. The following table from the International Energy Agency sets it out well.[viii]

Figure 4: Different timescales of power system flexibility

Source: OECD/IEA, Table 2.1, p.19

Source: OECD/IEA, Table 2.1, p.19

The ISA Report speculates that, “It is not clear how much back-up is needed. This will depend on the technology mix. If we had a complete solar and wind system, one-and-a-half days would seem reasonable, although this would probably not guarantee total reliability. One day would seem too low.”

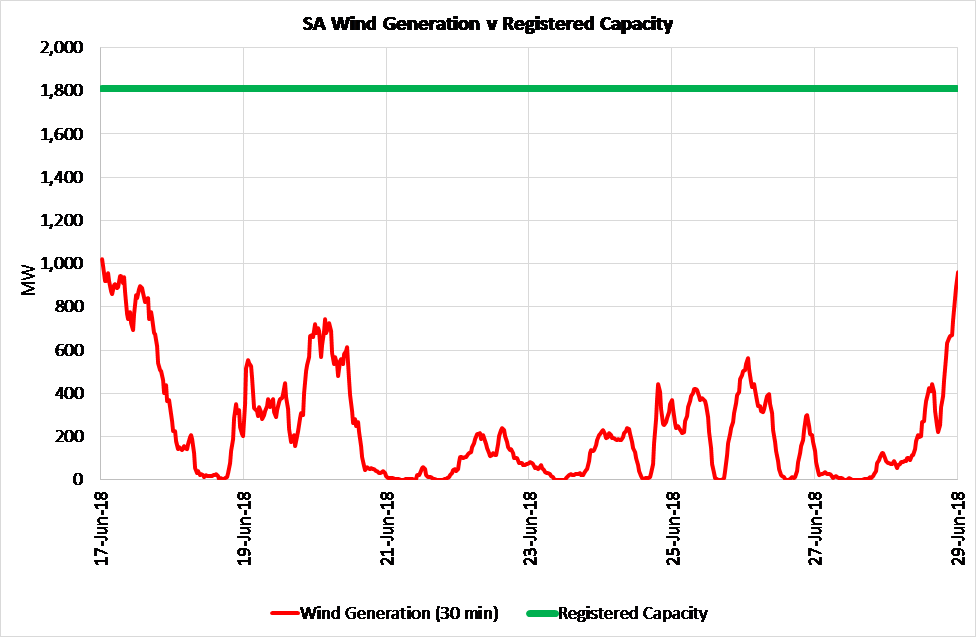

A quick review of available wind data suggests this is simplistic and inappropriate. See for example the following graph showing ten days in June last year.

Figure 5: SA Wind Generation v Registered Capacity

Source: AEC analysis of NEM data

Source: AEC analysis of NEM data

In this circumstance 1½ days of backup would be inadequate unless there were significant over-build to ensure demand was met.

The solution

The solution is to include a range of technologies with different characteristics to support the increasing variability of demand. For example, batteries can provide very fast response but for limited duration, whereas closed-cycle gas turbines are slower to come online, but, subject to fuel availability, can generate for longer.

These technologies don’t need to be standalone either. They can work in concert with variable renewable energy to “firm” its supply, whether that be on a physical basis,[ix] or a contractual basis.[x] In addition, the recently legislated Retailer Reliability Obligation will compel retailers to firm their supplies when there is a forecast shortfall.[xi]

The authors propose that nuclear power may be an option to provide that flexibility, however existing plants are notoriously inflexible and incapable at this role. There are proposals for more flexible plants in the future, but there is uncertainty whether it can be ramped up and down to the extent and in the required timeframes so match renewable energy fluctuations. See, for example, the paper Can Reactors React? – Is a decarbonized electricity system with a mix of fluctuating renewables and nuclear reasonable?[xii] This is further considered in the most recent IEA Report, “… nuclear power plants can be operated in a flexible manner, although this may require minor changes in plant design.”[xiii],[xiv]

In any case, the avoided marginal costs of reducing output of a nuclear plant would appear to be near zero and possibly negative – it may even be cheaper and simpler to spill renewables than ramp nuclear. The more conventional approach to “firm” the supply of renewables is to use low capital cost/high marginal cost/highly flexible plants, such as gas or liquid-fired peaking plant.

How do we encourage these solutions?

The ISA Report lists ten policy suggestions. We will concentrate on four of the most relevant ones.

Technological Neutrality

The report proposes that policies should be neutral to technology and market structures. It suggests that markets require more competition, alleging that there is gaming of price setting procedures in the NEM. This has previously been refuted by the Australian Energy Regulator (AER) in its NSW Electricity Market Advice[xv] and Hazelwood Advice.[xvi]

It then goes on to suggest establishment of an expert panel to provide technical guidance to government on issues related to technology, as well as suggesting that to provide “technological choice”, capacity to build or operate a nuclear facility should be fostered.

However there already exists the Office of the Chief Scientist, currently filled by Alan Finkel AO, who provides advice to Government on such matters, including by means of the National Science and Technology Council. We also have the CSIRO itself and many energy market institutions, such as the recently created Energy Security Board.

Long-term Market Architecture

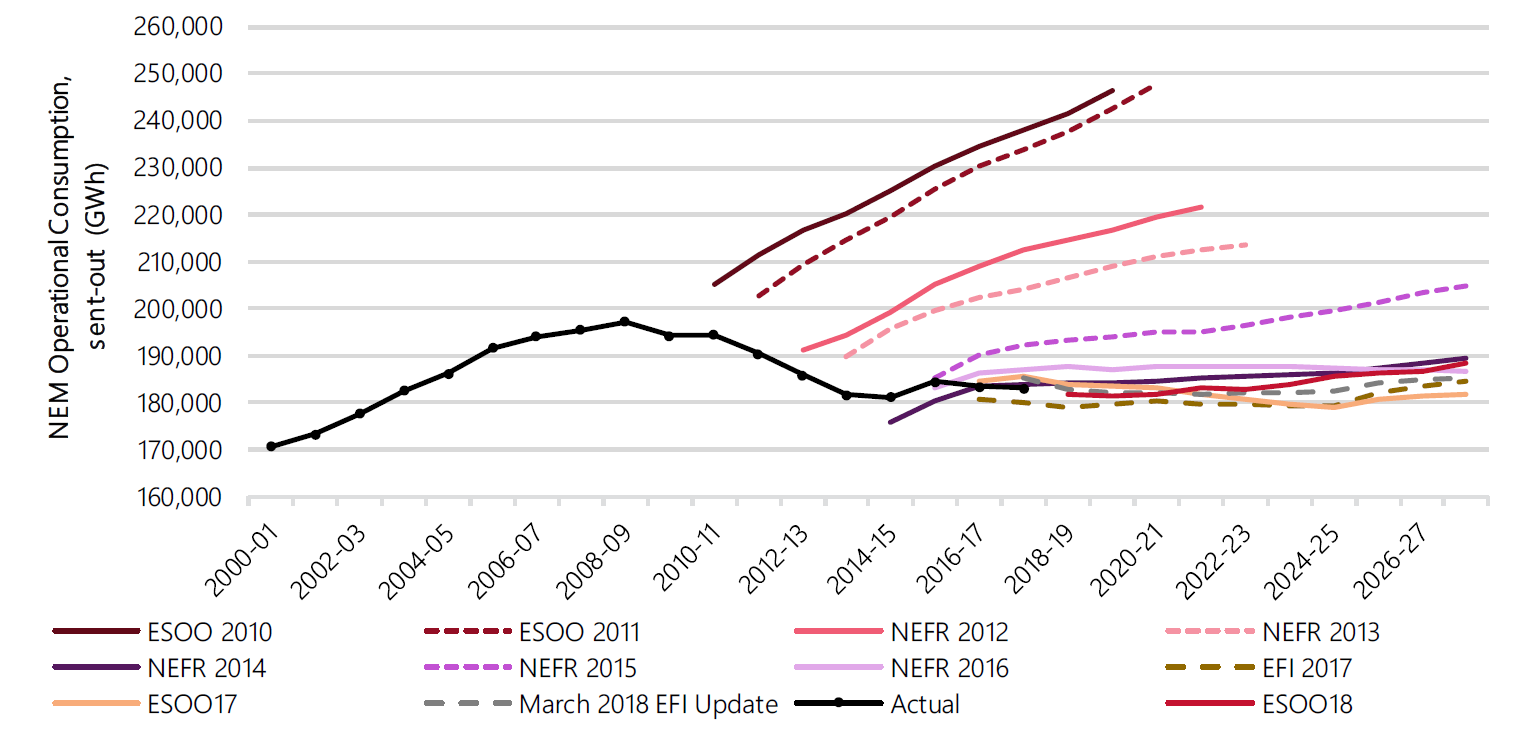

The authors suggest that the NEM should be focused on the longer term by having auctions of longer-term contracts of 20 years’ duration or longer written by the government.

In response to this, the AEC suggests this is effectively a reversal into government-managed electricity systems that was abandoned in the 1990s due to the waste and inefficiency that such a model created.[xvii] In the existing liberalised electricity market, there are already such long-term arrangements in place via power purchase agreements, where risks are borne by investors rather than customers, for example in over-estimating demand growth as occurred in many government owned electricity utilities in the 1980’s. These risks continue, and are evident in the following graph:

Figure 6: Operational consumption forecasts versus actual, 2010-18

Source: AEMO, 2018 Electricity Statement of Opportunities, August 2018, Figure 41, p.81

Source: AEMO, 2018 Electricity Statement of Opportunities, August 2018, Figure 41, p.81

Governments to formally underwrite markets[xviii]

The ISA Report suggests that Government may eventually have to act as underwriter of last resort in Australia’s electricity markets, if all other proposals fail to reduce emissions.

As the AEC submitted to the Underwriting New Generation Investments Public Consultation Paper,[xix] the AEC is of the firm opinion that government intervention in the investment process distorts the wholesale electricity market and would only be driven by a continued absence of consistent government policy, as has occurred over the past decade. In summary, the AEC opposed the UNGI Programme on the basis of:

- the proposal being unnecessarily rushed;

- the need for reliability via additional plant not being proven by AEMO’s current data (and is being further reinforced by the Retailer Reliability Obligation);

- separation of the underwritten plant from important market incentives; and

- the consequent market distortion stifling private investment, leading to unintended consumer outcomes such as the premature retirement of existing plant.

Public Authority for Transmission and Distribution Planning

The ISA Report observes that distribution and transmission networks are natural monopolies that require planning decisions in the public interest. It suggests that AEMO could be strengthened to perform this planning role.

However AEMO already conducts a considerable amount of such planning, in the form of the NEM Electricity Statement of Opportunities,[xx] Integrated System Plan[xxi] and the Energy Adequacy Assessment Projection.[xxii] When these businesses are regulated, the AER reviews their spending plans against these documents. Distribution businesses also conduct similar studies that are subject to the AER’s review.[xxiii]

Conclusion

The ISA Report offers an interesting perspective from those outside the industry. Although its authors were consciously seeking to challenge existing thinking, a proportion of its discussion and conclusions could have been significantly improved by a little more research, and consultation with those who are more familiar with industry’s workings. One thing upon which we can all agree is the need for government policy certainty. However the AEC would consider direct government involvement in the market as the antithesis of certainty.

[i] Available at https://www.industrysuper.com/media/modernising-electricity-sectors/

[ii] The “energy security costs” listed include “back-up against failure of generation to meet demand over a longer period”. This should more properly be characterised as reliability costs.

[iii] Lazard, Lazard’s Levelized Cost of Energy Analysis – Version 12.0, 2018

[iv] Not cited

[v] Energy Innovation Reform Project, What will advanced nuclear power plants cost? A Standardized Cost Analysis of Advanced Nuclear Technologies in Commercial Development, undated but assumed to be 2018

[vi] Graham, P.W., Hayward, J., Foster, J., Story, O. and Havas, L., GenCost 2018, December 2018.

[vii] AEMO, Quarterly Energy Dynamics Q1 2019, 7th May 2019

[viii] International Energy Agency, Status of Power System Transformation 2018 – Advanced Power Plant Flexibility, May 2018

[ix] For example, Lincoln Gap Wind Farm. See http://lincolngapwindfarm.com.au/

[x] See https://www.energycouncil.com.au/analysis/firming-renewables-the-market-delivers/

[xi] The draft rules for which are available at http://www.coagenergycouncil.gov.au/publications/retailer-reliability-obligation-rules

[xii] Craig Morris, Can Reactors React? – Is a decarbonized electricity system with a mix of fluctuating renewables and nuclear reasonable?, Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies, January 2018

[xiii] International Energy Agency, Nuclear Power in a Clean Energy System, May 2019, p.14

[xiv] ibid., p.72ff

[xv] AER, AER Electricity Wholesale Performance Monitoring – NSW Electricity Market Advice, December 2017

[xvi] AER, AER Electricity Wholesale Performance Monitoring – Hazelwood Advice, March 2018

[xvii] See https://www.energycouncil.com.au/analysis/happy-20th-birthday-national-electricity-market/

[xviii] We assume this is what’s meant by the authors saying that “governments may need to formerly underwrite markets”.

[xix] Available at https://www.energycouncil.com.au/media/14522/20181109-aec-underwriting-investments-final.pdf

[xx] See https://www.aemo.com.au/Electricity/National-Electricity-Market-NEM/Planning-and-forecasting/NEM-Electricity-Statement-of-Opportunities

[xxi] See https://www.aemo.com.au/Electricity/National-Electricity-Market-NEM/Planning-and-forecasting/Integrated-System-Plan

[xxii] See https://www.aemo.com.au/Electricity/National-Electricity-Market-NEM/Planning-and-forecasting/Energy-Adequacy-Assessment-Projection

[xxiii] See https://www.aer.gov.au/networks-pipelines/guidelines-schemes-models-reviews/distribution-annual-planning-report-template

Related Analysis

The return of Trump: What does it mean for Australia’s 2035 target?

Donald Trump’s decisive election win has given him a mandate to enact sweeping policy changes, including in the energy sector, potentially altering the US’s energy landscape. His proposals, which include halting offshore wind projects, withdrawing the US from the Paris Climate Agreement and dismantling the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), could have a knock-on effect across the globe, as countries try to navigate a path towards net zero. So, what are his policies, and what do they mean for Australia’s own emission reduction targets? We take a look.

UK looks to revitalise its offshore wind sector

Last year, the UK’s offshore wind ambitions were setback when its renewable auction – Allocation Round 5 or AR5 – failed to attract any new offshore projects, a first for what had been a successful Contracts for Difference scheme. Now the UK Government has boosted the strike price for its current auction and boosted the overall budget for offshore projects. Will it succeed? We take a look.

Energy transition understanding limited: Surveys

Since Graham Richardson first proposed a 20 per cent reduction in Australia’s greenhouse gas emission levels in 1988, climate change and Australia’s energy transition has been at the forefront of government policies and commitments. However, despite more than three decades of climate action and debate in Australia, and energy policy taking centre stage in the political arena over the last decade, a reporting has found confusion and hesitation towards the transition is common among voters. We took a closer look.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.