What is the price tag for policy inaction?

Government inaction to progress our energy and climate policy has resulted in partisan politics driving uncertainty in energy and higher costs. In our submission to the Review into the Future Security of the National Electricity Market (Finkel Review)[i], we estimate that we are now paying the equivalent of in excess of $50 tonne carbon price.

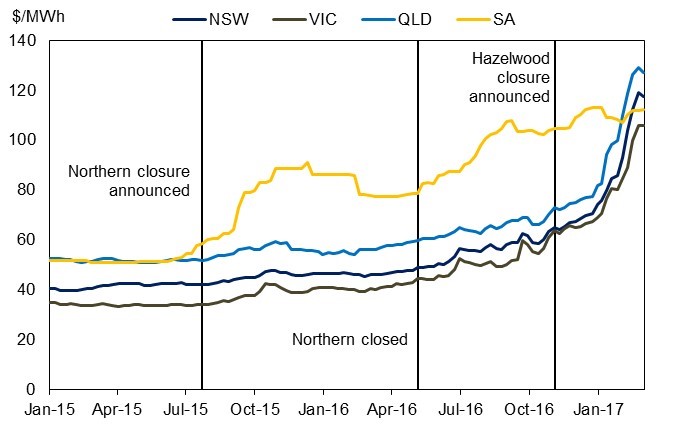

The current price impact of government policies (or lack of them) to decarbonise the electricity system extends well beyond the cost of carbon pricing, renewable subsidies and grant funding for related projects. Since 2012, and following the impending closure of Hazelwood power station, more than 5,000MW of firm generation will have left the National Electricity Market (NEM). The withdrawn capacity has not been replaced. The reduction in the supply-demand balance and a recovery in demand since 2015 has significantly increased prices in the forward contract market for electricity (refer to Figure 1).

Figure 1: Contract prices in NEM regions, for delivery in CY 2017

Source: NEM Review, 2017

Higher wholesale prices are a signal by the NEM for investors to enter the market and increase supply. Investors have been unable to replace retired generation because of sustained policy uncertainty over the past decade rendering new generation investment currently unbankable. In Australia, the lack of national policy certainty is now the single biggest driver of higher electricity prices.

Forward contracts for energy provide an indicator of the expectations about the supply/demand balance for energy. Wholesale market prices vary widely, so energy buyers and generators contract with one another in the long term to hedge their risk to the volatile wholesale price. If the forward contract price for energy rises (as shown in Figure 1) this is a reflection of rising expectations about risk in the future and the higher physical price for energy. Forward contract prices are currently trading at $100-$120 MWh for energy delivered in 2017[ii] (see Table 1).

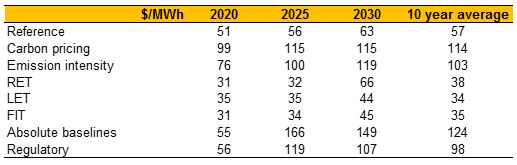

When compared to a reasonable estimate of the underlying long term cost of supply (absent carbon constraints), we find the additional cost due to policy uncertainty and risk in the price of electricity. We approximate the long term cost of supply to a 10 year average of wholesale prices. The Climate Change Authority modelling of climate policy scenarios, conducted by Jacobs[iii] provides the first ten years modelled from 2020 to 2030 (see Table 2). When an emissions intensity figure of 0.92 tonnes/MWh for the National Electricity Market as at the end of 2016[iv] is applied it is possible to estimate the price of carbon. The contract price for electricity is considered to include a risk premium relative to spot prices, so we applied a 15 per cent risk premium. Taking the difference between the long term cost of supply (around $57 MWh) and the current contract price ($100-120 MWh) the electricity cost of sustained national policy inaction is effectively equivalent to a carbon price of more than $55 a tonne.

Table 1: Contract prices in NEM regions, for delivery in CY 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020

Source: ASX Energy, 2017

Table 2: average wholesale spot prices in NEM regions under climate policy scenarios

Source: Jacobs for the Climate Change Authority, 2016

This suggests that development of durable and effective national energy and climate polices, which return investment to the market, are likely to reduce electricity prices over time. By reducing volatility and risk in the market, contract prices should be lower and lower the overall cost of supplying electricity to consumers.

The current price impact of government policies to decarbonise the electricity system extends well beyond the literal cost of carbon pricing, renewable subsidies and grant funding for related projects. Higher wholesale prices are a signal by the NEM for investors to enter the market and increase supply. However, investors in efficient plant are withdrawing their supply unable to make a commercial case to remain in the market such as Pelican Point Power Station in South Australia. The sustained policy uncertainty over the past decade combined with the existing policies in place (such as the moratorium on conventional gas exploration or renewable targets), make accurately estimating the returns on an investment decision difficult.

The current policy settings imposed on the markets and the regular change in policy settings have undermined confidence in energy assets. If a policy supports new generation irrespective of the market price (such as a renewable energy target or a government underwriting a contract for difference with a generator) it may incentivise generation when demand is not there, moving the market away from the least-cost supply mix and increasing overall costs. There should be an emphasis on policy outcomes rather than technology outcomes, supporting the government’s technology neutral policy principle. This will enable all available technologies to be used in the most efficient way and for consumers and their purchasing to lead the energy transition. It is time to move he political debate on and stop asking consumers to pay higher prices because of political partisanship which creates risk and uncertainty.

[i] Australian Energy Council, 2017, Submission to the Preliminary Report of the Review into the Future Security of the National Electricity Market, https://www.energycouncil.com.au/submissions/

[ii] ASX Energy, 2017, Base futures prices as at 07/03/2017, https://www.asxenergy.com.au/

[iii] Jacobs for Climate Change Authority, 2016, http://climatechangeauthority.gov.au/reviews/special-review/modelling-illustrative-electricity-sector-policies

[iv] AEMO, 2016, CDEII results – summary results 2016, https://www.aemo.com.au/-/media/Files/CSV/CO2EII_SUMMARY_RESULTS_2016.csv

Related Analysis

2025 Election: A tale of two campaigns

The election has been called and the campaigning has started in earnest. With both major parties proposing a markedly different path to deliver the energy transition and to reach net zero, we take a look at what sits beneath the big headlines and analyse how the current Labor Government is tracking towards its targets, and how a potential future Coalition Government might deliver on their commitments.

The return of Trump: What does it mean for Australia’s 2035 target?

Donald Trump’s decisive election win has given him a mandate to enact sweeping policy changes, including in the energy sector, potentially altering the US’s energy landscape. His proposals, which include halting offshore wind projects, withdrawing the US from the Paris Climate Agreement and dismantling the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), could have a knock-on effect across the globe, as countries try to navigate a path towards net zero. So, what are his policies, and what do they mean for Australia’s own emission reduction targets? We take a look.

A farewell to UK coal

While Australia is still grappling with the timetable for closure of its coal-fired power stations and how best to manage the energy transition, the UK firmly set its sights on October this year as the right time for all coal to exit its grid a few years ago. Now its last operating coal-fired plant – Ratcliffe-on-Soar – has already taken delivery of its last coal and will cease generating at the end of this month. We take a look at the closure and the UK’s move away from coal.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.