Government’s big stick: What does it hit?

This week has been tumultuous not only for the political class but also for the energy sector with the Federal Government at the time of writing effectively putting the National Energy Guarantee (NEG) into limbo by deciding it would not proceed with the emissions guarantee. This was greeted with dismay by not only the energy industry, but also energy users, business groups and a very broad range of stakeholders.

In its place the government said that it would take a “big stick” to energy companies.

One aspect, designed to “drive lower electricity prices for households and small businesses”, was the introduction of a default retail price offer.

To put a default price in place the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) and the Australian Energy Regulator (AER) will be directed to set a price for households and small to medium sized businesses to replace current standing offers in New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and South-East Queensland.

Assuming the states and territories support the move to re-regulate prices in this way or, alternatively, the Federal Government is able to legislate the default offer into law in the absence of agreement from the various jurisdictions, what is it likely to achieve?

A Closer Look

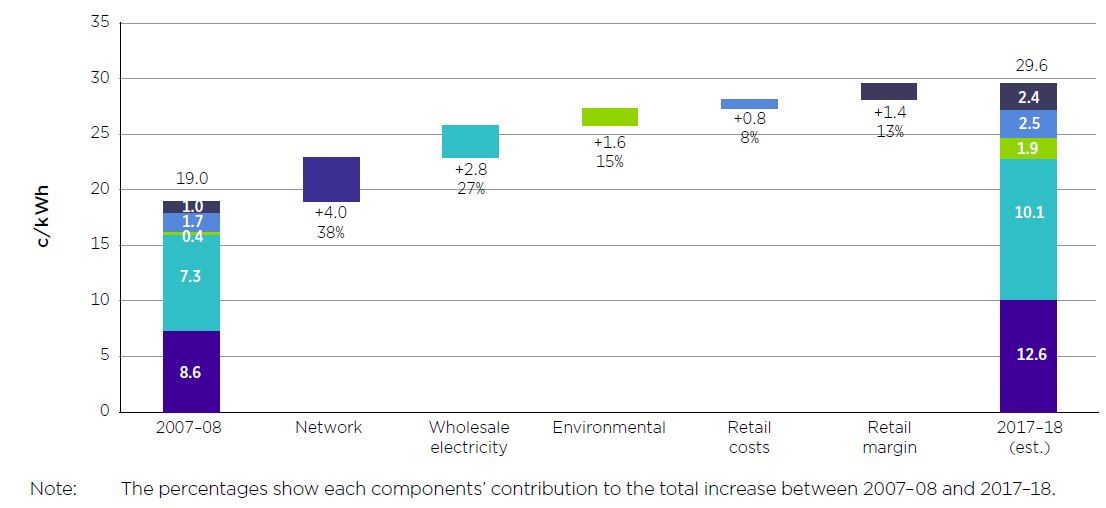

The measure is intended to address increases in electricity bills for standing offer customers (the government pointed to a 56 per cent increase in electricity prices over the past 10 years based on c/kWh), and provide greater clarity for households and businesses. The ACCC has argued that a default price will provide greater transparency for customers to assess market offers and discounts.

The 56 per cent rise in power prices in the past decade shows that across the National Electricity Market (NEM) 38 per cent of the rise in power bills was driven by network costs, while 27 per cent came from higher wholesale prices. There was a 15 per cent increase in the cost of government environmental or green schemes (such as solar feed-in tariffs), while retail costs grew 8 per cent in the period and retail margins increased 13 per cent increase over the decade (see figure 1). Only the retail margin would be impacted by the proposed default price.

Figure 1: Change in average residential customer effective prices (c/kWh) from 2007-08 to 2017-18 NEM-wide (real $2016-17 ex GST)

Source: ACCC

Source: ACCC

The default price is designed in a similar manner to other regulated tariffs of the past, and will replace the existing standing offers in non-regulated jurisdictions (New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and South-East Queensland). It is not clear if a federally set default price would necessarily be welcomed by states, particularly those that have more recently deregulated their markets.

The percentage of customers on standing offers ranges from 7 per cent in the most mature competitive market of Victoria to 19 per cent in SE Queensland, which has only been de-regulated since 1 July 2016. In SA 11 per cent of customers are on standing offers while there are 18 per cent of customers on these tariffs in NSW (the state deregulated on 1 July 2014). The introduction of a default price will not in itself reduce the price for any customer who has entered into a market contract with a retailer.

The number of customers on standing offers tends to decrease year on year as more customers engage with the markets. In addition, the number is likely to be significantly lower than reported, given that the ACCC’s final report will not fully reflect the efforts by retailers, since the government’s roundtables, to contact those on standing offers to encourage them to shift to cheaper market offers.

As noted the risk of highly prescriptive actions to lower prices in the short-term is that they could lead to unintended consequences in the longer term. It will be difficult for regulators to get the default price right given the variation in state energy markets and across distribution networks – set too low and it could see smaller retailers pushed out of the market. Set too high and customers will be paying more than they need to.

The Grattan Institute pointed to potential issues: “Direct regulation of retail prices might deliver lower margins for retailers but could just lead to higher wholesale margins and little if any net gain for consumers.”

Consumers would be better served by regulators and governments working closely with retailers to simplify the comparison of offers. These measures will have significantly greater long term outcomes for the vast majority of customers than a political fix to benefit a relative few.

Other Measures

The default offer was one of several measures announced by the Federal Government out of 56 recommendations made by the ACCC. Many of the recommendations relate to actions that need to be undertaken by various governments, such as ending their solar premium FIT and writing down the value of network assets.

We will take a closer look at some of the other steps being introduced in future EnergyInsiders. Additional measures accepted and announced by the Federal Government this week included:

- Limiting market power by placing a cap on the share of generation a single participant can control in any one region (excluding investment in new capacity and noting the ACCC’s recommended 20 per cent cap).

- Greater monitoring of the market and market participants by the ACCC, including an inquiry and review in March next year, with further reviews every six months until [2023].

- A range of enforcement remedies and responses that could be applied if the ACCC identifies problems, ranging from court enforceable undertakings and a binding price cap right up to ordering divestiture of assets.

The divestment decision has attracted significant comment, particularly given it was expressly not recommended by the ACCC which considered divestment and described it as an “extreme measure” in any market, and not warranted in the NEM. The government qualified its move to allow divestment by stating it would only be a last resort. It is difficult to see the circumstances in which it would be used, but unfortunately it adds further uncertainty for investors and market participants on top of the continued lack of a climate and energy policy.

Given that it is estimated that investment of $25 billion[i] will be needed to replace older plants as they retire (excluding any additional investment that would be needed for the electricity network), it will require the kind of policy certainty that the NEG would have provided. That now appears to have vanished.

[i] New Investment, Newgrange Consulting

Related Analysis

Judicial review in environmental law – in the public interest or a public nuisance?

As the Federal Government pursues its productivity agenda, environmental approval processes are under scrutiny. While faster approvals could help, they will remain subject to judicial review. Traditionally, judicial review battles focused on fossil fuel projects, but in recent years it has been used to challenge and delay clean energy developments. This plot twist is complicating efforts to meet 2030 emissions targets and does not look like going away any time soon. Here, we examine the politics of judicial review, its impact on the energy transition, and options for reform.

Climate and energy: What do the next three years hold?

With Labor being returned to Government for a second term, this time with an increased majority, the next three years will represent a litmus test for how Australia is tracking to meet its signature 2030 targets of 43 per cent emissions reduction and 82 per cent renewable generation, and not to mention, the looming 2035 target. With significant obstacles laying ahead, the Government will need to hit the ground running. We take a look at some of the key projections and checkpoints throughout the next term.

Certificate schemes – good for governments, but what about customers?

Retailer certificate schemes have been growing in popularity in recent years as a policy mechanism to help deliver the energy transition. The report puts forward some recommendations on how to improve the efficiency of these schemes. It also includes a deeper dive into the Victorian Energy Upgrades program and South Australian Retailer Energy Productivity Scheme.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.