Gas and electricity bills: What's the story?

The energy debate in Australia continues to be hampered by ideological or partisan positions. This week a new report by the McKell Institute, “The Cost of Inaction”, that purported to model for the first time the impact of wholesale gas prices on household power bills in New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland was released.

Based on its modelling the report claimed that Australian households could be paying as much as $430 more for electricity by the end of next year unless wholesale gas prices are lowered.

The report was used by the Australian Workers Union (AWU) to support its campaign for a domestic gas reservation policy[i]. The AWU argues that the modelling should force a change of government policy on gas exports.

There is no doubt that gas prices can and do influence wholesale electricity prices, but the extent to which it does is very complex. To make any sort of estimate one must engage in detailed market modelling, attempting to model all generator bidding behaviour, demands, network constraints and other matters. The McKell Institute’s approach however avoids this by assuming a simple 100 per cent relationship, i.e. a 10 per cent increase in gas price will lead to a 10 per cent increase in wholesale electricity price. This could only hold if gas-fired electricity bidding purely reflected their fuel costs (ignoring, for example, their contracts and earning a return on investment) and if gas-fired generators set the wholesale market price continuously.

The Basis for the McKell Institute’s Gas ModelThe Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) reports that wholesale electricity costs account for 22 per cent, 24 per cent and 21 per cent of a residential electricity bill in New South Wales, Queensland and Victoria respectively. The current average wholesale gas price is estimated to be $9/GJ – this is based on the Finkel Review. If this $9/GJ wholesale price increases to $14/GJ, that represents a 56 per cent increase. Therefore the relevant proportion that wholesale electricity costs make up of a residential electricity bill should also increase by 56 per cent. In the case of Victoria, the 21 per cent the wholesale costs account for in a residential bill would increase to about 33 per cent, and therefore the residential electricity bill in total will increase by around 12 per cent (33 per cent minus 21 per cent). For NSW the increase would be just over 12 per cent and for Queensland it would be more than 13 per cent. Dollar estimates for the relevant increases are then calculated based on average household electricity consumption levels and gas prices of $6.30/GJ, $7.80/GJ, $8/GJ, $12/GJ, $14/GJ and $19/GJ. Key findings based on its modelling include: That “households in NSW, Queensland and Victoria are already paying approximately $151, $175, and $134 more per year on their household power bills respectively, as a result of the currently inflated wholesale gas price”. By 2019, the report estimates that using ACCC advised figures of where the wholesale gas price should have been in 2017, and with current policy settings, the average household will be paying:

Under the worst case scenario of a gas price wholesale average of $19/GJ, average households would be paying:

The report’s conclusions are presented with nearest dollar precision and classified by Federal electorate. The McKell approach holds all other things equal, so it ignores the potential impact of additional supply on future electricity prices, which was outlined by the Australian Energy Market Commission’s 2017 Residential Electricity Price Trends[ii] |

In the National Electricity Market (NEM), generators bid their generation into the market every five minutes. The Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) dispatches generators based on the price of bids, using the cheapest generator first and then the next cheapest and so on, until demand is met. The highest or the marginal bid that is dispatched sets a five minute price in each NEM region (each of the five NEM states – Queensland, NSW, Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia - is a region). Where an interconnector (the transmission lines between the regions) is operating at its full capacity, the marginal bids on either side of that interconnector will set the price for the upstream and downstream regions respectively.

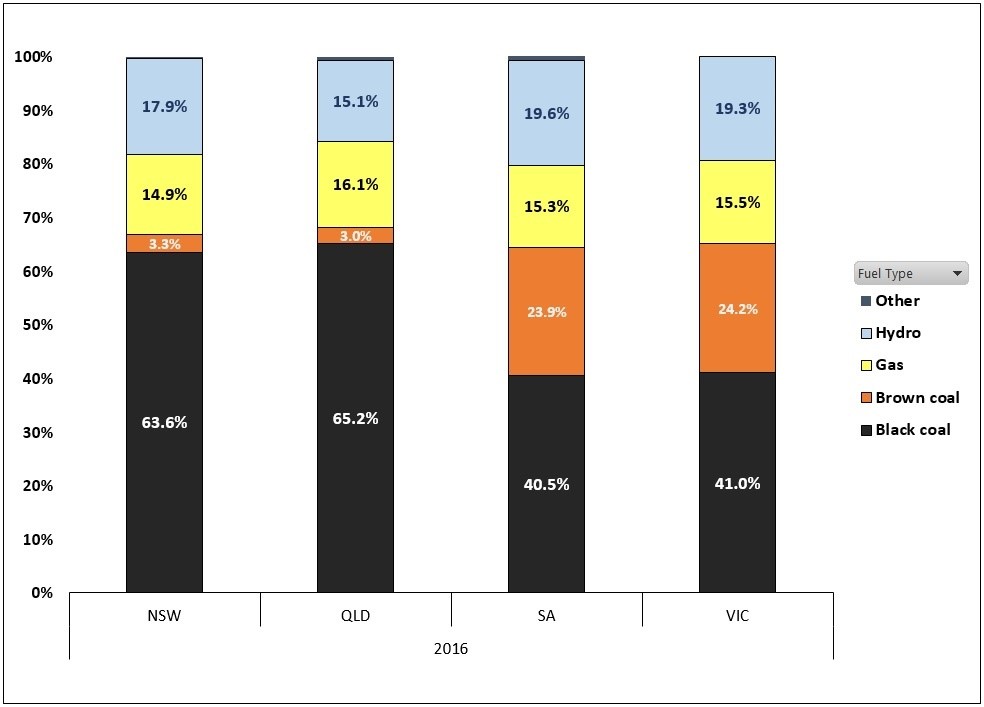

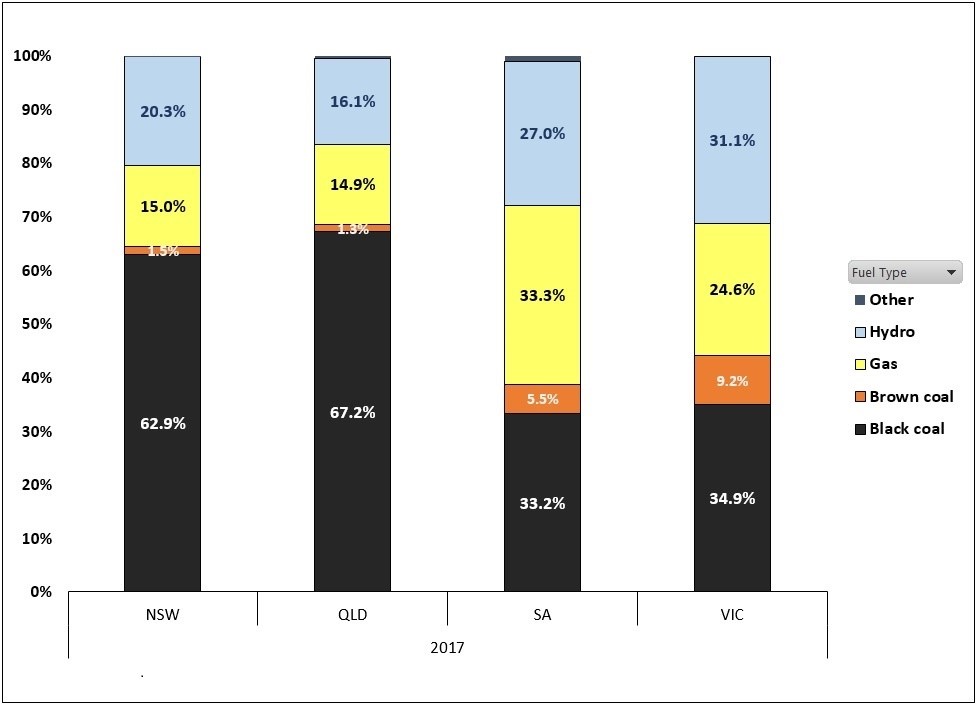

Available market data shows that gas is the price setter for significantly less of the time than assumed in the McKell Institute’s modelling. Other generators also significantly contribute to price setting, and their influence changes substantially over time and location. The following figures illustrate the point.

Figure 1: Price Setting By Fuel Type and NEM Region 2016

Source: Market Management Systems Data

Source: Market Management Systems Data

Figure 2: Price Setting By Fuel Type and NEM Region 2017

Source: Market Management Systems Data

Source: Market Management Systems Data

Price setting by fuel type

The market data in figure 2 shows that last year gas was the price setter for nearly a quarter of the time in Victoria, up from around 10 per cent in 2015. Hydro and black coal generation set the price for more of the year than gas generation. The influence of gas on wholesale prices in Victoria has grown, particularly with the retirement of the Hazelwood plant, but not to the extent assumed in the McKell Institute report.

These graphs are shown for illustration and are not intended to be used as an adjustment to McKell’s analysis, for example by reducing the pass through to the fraction of time when gas-fired generation did set price. Generator bids are affected by many complex matters including fuel price. And there would be secondary effects on non gas-fired generators too, for example hydro generators will have to respond by adjusting their bids to ensure their water remains appropriately rationed over time.

AEMC’s Assessment

The McKell approach was a with/without comparison: holding everything else equal, if gas prices were $/GJ lower, electricity customers would pay $Y less. Whilst they did not purport to analyse underlying pricing developments over time, it is worthwhile to consider some recent reputable price predictions for context. The Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) in its most recent assessment of electricity price trends, forecast price increases between 2016/2017 and 2017/2018 due to a combination of higher gas prices and the withdrawal of firm generation. In particular the AEMC points to:

- The retirement of Northern coal power station (546 MW) in May 2016 and the Hazelwood coal power station (1,600 MW) in March 2017.

- Closure of the Smithfield gas power station (171 MW)

- South Australia’s Pelican Point gas-fired power station (239 MW) returning to service in 2017/18, although the increased gas prices increase its operating costs

- The withdrawal of the Tamar Valley gas power station (208 MW) in 2016/17

The AEMC has also forecast that wholesale prices will moderate in the period 2018-2019 and 2019-2020 as an expected 5300 MW of new generation (which includes an estimated 4900MW of renewable generation) comes into the NEM: “In 2019/20, this 4,900 MW of new renewable generation is expected to represent around 10 per cent of generation capacity and 8 per cent of energy output in the NEM ... the LRET scheme design exerts downwards pressure on wholesale prices in the short-term (reporting period)”[iii].

It also points to the return to service of the Swanbank E gas power station (385 MW) in Queensland and expected lower short-run costs for South Australian gas plants in 2019/20 due to the pass through of certificate revenue from South Australia’s Energy Security Target, which was announced in March last year.

Conclusion

The Age[iv] reported that the AWU is seeking to use the McKell Institute’s projected impact on house-hold prices to lobby and draw policy interest to the issue of gas reservation. The scenarios consider the impact on household electricity costs from gas prices ranging from $6.30/GJ to $19/GJ.

The report mounts the case for more government action on gas supplies, but limits its commentary to export gas and Federal Government action. It appears to ignore the impact of state and Territory-based bans and limitations on the development of additional gas supplies.

Attempts to assess the impact of generation mixes on price trends is useful and is undertaken annually by the AEMC in its price trend reports. The McKell Institute’s work seeks to present precise price increases for households, but precision is lacking in its approach. Policy consideration should rely on more sophisticated modelling of the electricity market in order to assess potential impacts as a result of changes in fuel costs.

[i] Australian Workers Union, Media Release 5 February 2018, “With Link Between Power Bills and Gas Price Crisis Exposed, Turnbull Must Move Urgently”

[ii] AEMC, 2017 Residential Electricity Price Trends, Dec 2017

[iii] ibid

[iv] The Age, 5 February 2018, “Power bill hike of $430 predicted”

Related Analysis

2025 Election: A tale of two campaigns

The election has been called and the campaigning has started in earnest. With both major parties proposing a markedly different path to deliver the energy transition and to reach net zero, we take a look at what sits beneath the big headlines and analyse how the current Labor Government is tracking towards its targets, and how a potential future Coalition Government might deliver on their commitments.

Is increased volatility the new norm?

This year has showcased an increased level of volatility in the National Electricity Market (NEM). To date we have seen significant fluctuations in spot prices with prices hitting both maximum price caps on several occasions and ongoing growth in periods of negative prices with generation being curtailed at times. We took a closer look at why this is happening and the impact this could have on the grid in the future.

Is there a better way to manage AEMO’s costs?

The market operator performs a vital role in managing the electricity and gas systems and markets across Australia. In WA, AEMO recovers the costs of performing its functions via fees paid by market participants, based on expenditure approved by the State’s Economic Regulation Authority. In the last few years, AEMO’s costs have sky-rocketed in WA driven in part by the amount of market reform and the challenges of budgeting projects that are not adequately defined. Here we take a look at how AEMO’s costs have escalated, proposed changes to the allowable revenue framework, and what can be done to keep a lid on costs.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.