EVs: UK ponders how to get the (charge) timing right

The United Kingdom’s energy regulator, the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem), has released a Future Insights paper[i] to consider how an increasing number of electric vehicles (EVs) will affect the energy system, consumers and regulatory approaches.

The energy sector regulatory framework was not designed explicitly with EVs in mind and, as Ofgem notes, assumes supply to the home, rather than mobile demand that will draw electricity at home, work or at potentially thousands of locations.

It expects the shift to EVs to challenge key industry arrangements including settlement, how the industry balances and settles demand and supply, and challenge current arrangements for accessing and using the electricity network.

As a result regulation will need to adapt to provide predictability to the EV market and protection to EV users. The scale of uncertainty around the uptake of the new cars, charging behaviours, as well as the blurring of typically separated sectors (energy and transport) also represents a challenging prospect.

Increasing use of EVs could have considerable implications for the energy system, for example inflexible charging could add to peak demand and require expensive network reinforcements.

Ofgem argues that industry should focus on minimising overall system costs for all consumers (including non-EV users) by seeking to make more efficient use of our existing assets, before considering reinforcement.

It argues that the development of new markets that provide flexibility will play a key role by incentivising or automating the shifting of load away from peak demand, even if total demand increases. This means network businesses should not expect to be remunerated for reinforcement alone when more cost-effective solutions exist.

The regulator envisages that flexible charging could enable cost-effective decarbonisation of the transport sector and ensure that the grid is used in a smarter and more flexible way.

Key regulatory considerations include efficient investment in infrastructure, improving access to charging, how costs and benefits are distributed, and technological interoperability.

Not Even

Overall Ofgem anticipates that the transition to EVs should bring substantial benefits for energy consumers – electricity flows will be increasingly complex and bi-directional, particularly if EVs are used to feed power back into the grid through vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technology.

But elsewhere it expects that impacts associated with EVs will not be distributed equally. This is true, it says, in terms of where flow on the network will change due to EV charging, and how costs and benefits are distributed across different socio-demographic groups.

If EV users choose to charge during peak times, they will impose considerable costs which will be borne by all consumers. An enduring charging regime should ensure costs are distributed fairly and EV users face charges that are reflective of the costs or benefits they are imposing on the system.

“Vulnerable customers, or those who are currently unable to share in many of the benefits of EVs, are likely to object to subsidising more affluent early adopters of EVs,” the paper states.

The least deprived decile of the population accounts for more EV chargepoints than any other decile, with the mean EV user in the 7th decile and the median in the 8th – a strong indicator that current uptake is heavily linked to a person’s socio-demographic status. “This raises concerns regarding how system costs are currently allocated,” Ofgem says.

If inflexible charging leads to reinforcement, poorer consumers may reasonably object to paying for system costs associated with EV ownership by predominantly more affluent consumers.

If charging is managed flexibly all consumers (including those without EVs) “should benefit from a more optimised energy system, and avoided reinforcement costs".

Ofgem also argues that there are equitable arguments for adopting a regime that ensures costs are imposed on those who create them – this can occur with cost-reflective charges for connecting EV chargepoints to the network, and cost-reflective price signals that mean consumers who choose to charge during peak times will pay proportionately for the system costs incurred from their behaviour.

Flexible and fast charging is essential for facilitating the transition to EVs in the most cost-effective way, by enabling all consumers (including those who do not own an EV) to benefit from a more optimised energy system, and avoiding grid reinforcement costs.

EVs in the UK

In the UK the number of EVs on the road has grown from 4000 in 2013 to around 160,000 in June this year. While this represents a significant increase, EVs remain a fraction of the UK’s total car fleet of 31.2 million cars (around 1 in 200 vehicles).

The annual uptake of EVs has jumped from 2254 new registrations in 2012 to almost 50,000 in 2017. Meanwhile, the total number of public chargepoint connectors has grown more than 500 per cent and stands at 16,000 across more than 5600 locations.

The number of rapid chargepoints has grown from 79 (2012) to more than 3400 in May 2018, representing the largest rapid chargepoint network in Europe.

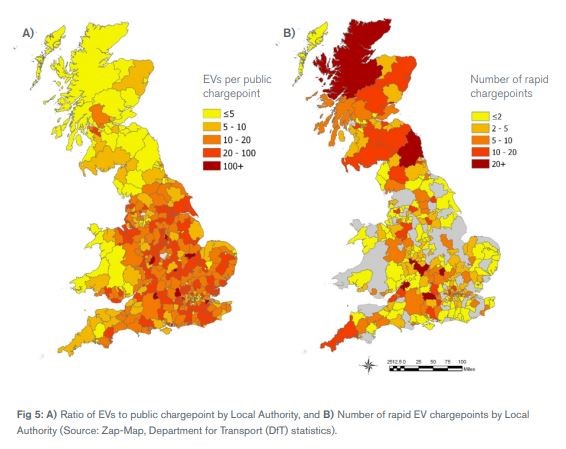

There is around one public chargepoint for every eight EVs in the UK, but the distribution of these is uneven (figure 1). The number of rapid chargepoints, which encourage drivers to charge their cars while travelling, has grown 900 per cent since 2013, well above the 30 per cent growth in slow chargers. Despite the strong growth in rapid chargers the limited distribution of them in some regions is seen as a likely barrier to EV uptake.

Figure 1: EVs per Chargepoint and Number of Rapid Chargepoints

Source: Ofgem

Home is Where the Charge Is

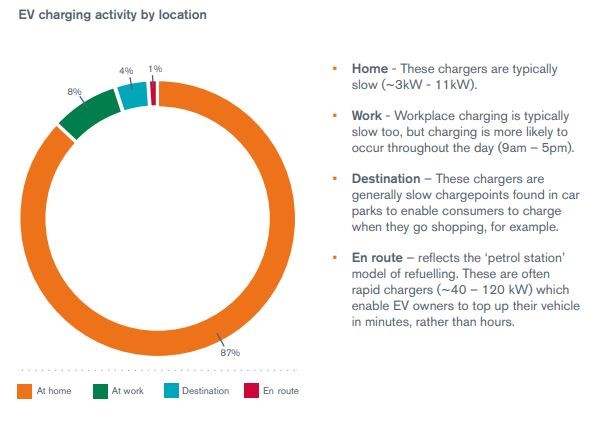

By far the majority of private EV charging currently occurs at home (see figure 2) and at peak demand times, which means impacts on the network are likely to be greater where constraints already exist.

The implications for the grid may mean that some reinforcement is needed, potentially leading to higher costs for all consumers.

Figure 2: EV charging activity by location

Source: Ofgem

EV charging could be offset by microgeneration if charging happens when solar PV systems are exporting to the grid, and as the economics of storage improves it is expected to allow stored electricity to offset the demand from EV charging and heat pump use.

Ofgem argues that to maximise the benefits of EVs electricity demand, the cars should be integrated in a “smart and flexible way”.

It argues that flexible charging can complement a system with variable renewable generation in two ways:

- Promoting charging when there is excess generation; and,

- Alleviating network constraints by shifting charging to times when there is sufficient network capacity.

This will demand smart systems that can communicate with the wider energy system in real time – it will demand smart meters, half-hourly settlements, and time of use tariffs.

Ofgem supports the idea that consumers could be rewarded for being flexible with their demand, but also being required to pay a premium if their behaviour adds to peak demand or local congestion – this would then reflect either the benefit they deliver or the costs they impose on the system.

But it does caution that there may be limits to the extent to which price-signals should penalise consumers who are less able to engage.

In assessing the impact of EV charging on the low voltage network the regulator found that:

- Flexible fast charging allowed the greatest number of EVs to connect to the network, due to higher load diversification compared to slow charging;

- Inflexible fast charging allowed the smallest number of EVs to connect, due to the limited capacity available at peak times;

- Flexible EV charging, even with the additional demand of heat pumps, allowed a comparable number of EVs to connect compared to inflexible slow charging, and considerably more compared to inflexible fast charging;

- For all inflexible charging (at peak) cases, EV uptake is constrained by the transformer limit; and,

- For all cases with flexible charging, EV uptake is constrained by the feeder limit.

Policy Implications

Ofgem found that the analysis had clear implications for policy – as smart, flexible solutions allow at least 60 per cent more EVs to connect to the existing electricity network before reinforcement needs to be considered. If “fast” charging is adopted, flexible solutions may allow up to six times more EVs to connect.

It also found that experience from retail markets showed that consumers don’t always engage in the market even when there are financial benefits.

In considering how to address this issue it points to numerous options:

- Consumers could be actively incentivised through price signals to charge at off-peak times.

- Consumers could opt-in to agreements for automated charging, within defined parameters, or other options for access such as off-peak or timed access.

- Through new flexibility markets, DNOs could contract directly with EV users or aggregators for flexibility services.

- Flexible charging could be established as the industry “default” where domestic charging would only happen at off-peak times, unless an override (requiring consumer action) was triggered.

- Flexible charging could be bundled with the cost of vehicle purchase (such as a discount on the purchase price) on a fixed term, or opt-out basis.

In rare cases where flexible charging fails to prevent constraint issues, curtailment of EV charging might still serve as a last resort backstop to avoid outages, although Ofgem sees this as occurring only in extreme situations.

Ofgem has proposed reforms[ii] that will give incentives for customers to charge EVs at the right time. The reforms are intended to free up existing grid capacity to allow new generators, including businesses or other organisations which want to generate their own power on-site, to get grid connected more quickly.

[i] https://www.ofgem.gov.uk/system/files/docs/2018/07/ofg1086_future_insights_series_5_document_master_v5.pdf

[ii] https://www.ofgem.gov.uk/publications-and-updates/ofgem-proposes-system-reforms-support-electric-vehicle-revolution

Related Analysis

The ‘f’ word that’s critical to ensuring a successful global energy transition

You might not be aware but there’s a new ‘f’ word being floated in the energy industry. Ok, maybe it’s not that new, but it is becoming increasingly important as the world transitions to a low emissions energy system. That word is flexibility. The concept of flexibility came up time and time again at the recent International Electricity Summit held in in Sendai, Japan, which considered how the energy transition is being navigated globally. Read more

Nuclear Fusion Deals – Based on reality or a dream?

Last week, Italian energy company ENI announced a $1 billion (USD) purchase of electricity from U.S.-based Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS), described as the world’s leading commercial fusion energy company and backed by Bill Gates’ Breakthrough Energy Ventures. CFS plans to start building its Arc facility in 2027–28, targeting electricity supply to the grid in the early 2030s. Earlier this year, Google also signed a commercial agreement with CFS. These are considered the world’s first commercial fusion-power deals. While they offer optimism for fusion as a clean, abundant energy source, they also recall decades of “breakthrough” announcements that have yet to deliver practical, grid-ready power. The key question remains: how close is fusion to being not only proven, but scalable and commercially viable, and which projects worldwide are shaping its future?

Community Power Network Trial: Potential risks and market impact

Australia leads the world in rooftop solar, yet renters, apartment dwellers and low-income households remain excluded from many of the benefits. Ausgrid’s proposed Community Power Network trial seeks to address this gap by installing and operating shared solar and batteries, with returns redistributed to local customers. While the model could broaden access, it also challenges the long-standing separation between monopoly networks and contestable markets, raising questions about precedent, competitive neutrality, cross-subsidies, and the potential for market distortion. We take a look at the trial’s design, its domestic and international precedents, associated risks and considerations, and the broader implications for the energy market.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.