Concerns remain post-Liddell

On Friday 20 November the modelling undertaken for the Liddell Taskforce was finally released, following the September release of the Taskforce report.

In its response to the Taskforce’s report, the Federal Government announced that 1000MW of new dispatchable capacity was required to replace the power station. It also warned the private sector that it had until April 2021 to reach final investment decisions on new plant or it would step in.

Without adequate dispatchable replacement capacity it forecast we could see wholesale prices rising by around 30 per cent to $80/MWh in 2024 and by up to $105/MWh by 2030.

This appears to be based on the no replacement scenario in the released modelling, conducted in 2019, which the author Frontier Economics describe as a “contrived case”. Amongst other assumptions, it is based on no new plant entering the market that is not already committed: “that new investment cannot occur regardless of how high prices may rise, though in reality high prices should increasingly drive new investment”.

Concerns about the replacement for Liddell since its planned closure was announced, are based around the potential reliability and price impacts, although as noted by the Liddell Taskforce, specific plans in train or recently implemented are intended to help mitigate these.

“They include interconnector upgrades, Snowy 2.0, Renewable Energy Zones, UNGI[i], the Retailer Reliability Obligation, Grid Reliability Fund, NSW Emerging Energy Program, Converting the Integrated System Plan (ISP) into Action, the NSW Electricity Strategy and the Wholesale Demand Response Mechanism[ii]”.

However, as the modelling was conducted in 2019 it clearly could not and did not anticipate the scale of the just legislated NSW Roadmap which, inter alia, proposes the underwritten investment of a minimum of some 14 GigaWatts of new NSW plant before 2030.

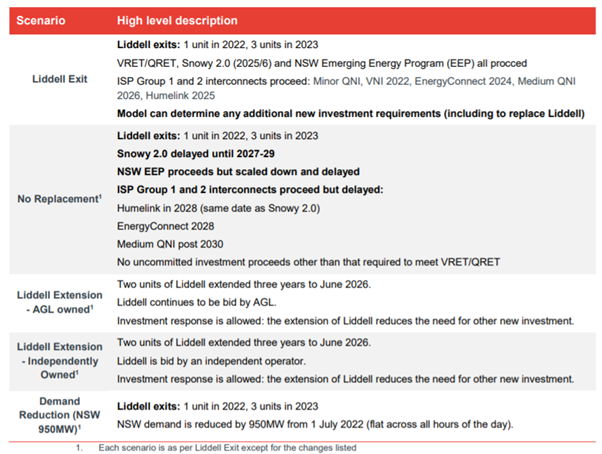

Below we summarise the scenario along, with three others that were considered.

The scenarios

Overall, the Liddell Taskforce found the modelling suggested Liddell’s planned closure could lead to a NSW wholesale price increase from the low $60s/MWh in 2022 to $75-$80/MWh in 2023–24, depending on the market response to deliver new capacity. The price is expected to moderate over the following years as Snowy 2.0 and more renewable energy capacity comes into the system, to average $71 over the five years to 2027–28.

The full range of key scenarios modelled for the Liddell Taskforce is summarised in the table below.

Figure 1: Summary of key scenarios modelled for the Liddell Taskforce

Source: Modelling of Liddell Power Station Closure Report

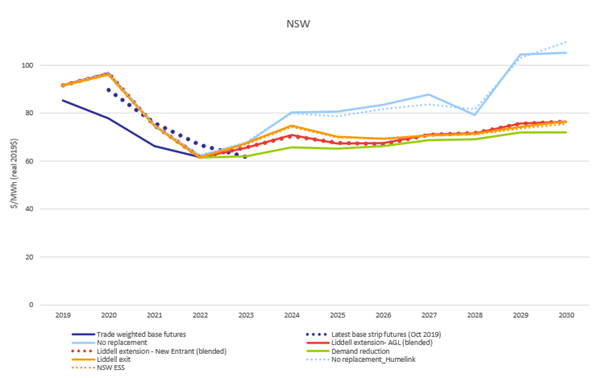

The price impacts are shown in Figure 2, based on the various key scenarios above.

Figure 2: Wholesale price comparison (median SPARK prices)

Source: Modelling of Liddell Power Station Closure Report

No replacement

The no replacement scenario assumes new investment cannot occur regardless of how high prices rise. It assumes that Snowy 2.0 is delayed by three years (to 2028) and no uncommitted investment occurs except that driven by the state-based renewable energy targets in Victoria and Queensland.

Humelink, a proposed project to strengthen transmission in southern NSW, and EnergyConnect between SA and NSW are also delayed and NSW’s Emerging Energy Program[iii] results in about half the expected capacity.

The scenario also assumes that the following do not proceed, compared to the Liddell Exit scenario:

- 530MW peak gas and 3700MW (uncommitted) wind in NSW;

- 770MW pumped hydro in Queensland (270MW up to 2028);

- 410MW battery and 460MW of wind in SA;

- 280MW gas in Victoria; and,

- 230MW gas and 340MW wind in Tasmania.

As a result, it forecasts the prices would rise above $80/MWh from 2024-28, with prices dipping in 2028 when Snowy 2.0 enters and Humelink and EnergyConnect allow more imports. Prices then rise again to around $100/MWh following the exit of Vales Point, Callide B and the start of unit closures at the Yallourn Power station in Victoria. With the increases “driven by the artificially assumed limit on any new entrant investment”.

Frontier Economics notes: “in reality, higher prices are increasingly likely to result in new entrant investment (such as NSW gas peakers, wind and pump hydro) which would limit some of the price increases”. It also includes the rider that the investment mix in this scenario is assumed and not a modelled outcome, “so the results should be interpreted accordingly”.

Frontier also modelled a no replacement sensitivity that allowed for 530MW of Humelink capacity from 2025, which resulted in lower prices from 2025-28 due to the removal of some of the constraint between Vic/Snowy and NSW. This did also indirectly lead to higher prices in 2030 because it impacted the timing of Victorian renewables entry to meet the Victorian Renewable Energy Target (but notes this is unlikely to occur).

Liddell exit

The Liddell exit scenario includes uncommitted investment entering the market, including, but not limited to, replacing Liddell’s capacity. Under this scenario Liddell’s capacity is mostly replaced by 500MW of gas peaking in NSW, with Snowy 2.0 and Humelink largely offsetting the dispatchable capacity lost. The new capacity does not replace the energy lost from Liddell (as opposed to the capacity), but this is largely replaced by new renewables. In this scenario around 1100MW of solar PV is already committed in NSW, 300MW of committed wind and a further 3700MW of non-committed wind enters after 2025.

In Queensland 270MW pumped hydro enters the market in 2024 and new hydro is expected to increase to 770MW by 2030, following further coal closures. An estimated 700MW solar and 1200MW wind is also committed in the state with an additional 1000MW of solar and 3000MW of wind expected to enter under Queensland’s RET.

In Victoria under this scenario, 500MW of solar and 2000MW of wind is committed with an additional 2500MW of wind expected to be driven by the state’s RET, while 570MW of peaking gas capacity is included in the model to offer more dispatchable capacity.

In NSW, median prices are forecast to fall to $62/MWh in 2022 before the Liddell exit. They rise to $68/MWh when one unit exits in 2023 and $75/MWh when the remainder of Liddell exits in 2024. Prices stabilise at around $70/MWh until Vales Point and Callide B also leave the market.

The price increases for other regions are much smaller: around $3/MWh each year in Queensland and SA and around $2/MWh in Victoria.

Liddell extension

The Liddell extension scenario assumes two of the power station’s four units are extended for three years, which limits the need for new capacity such as the 500MW gas peaking in NSW and 270MW of pumped hydro in Queensland, which are assumed to enter the market under the exit scenario.

While this scenario only delays the entry of wind capacity, it is forecast to reduce the requirement for gas peaking in NSW as well as reducing Victorian gas peaking by 280MW because it effectively bridges the Liddell plant to the entry of Snowy 2.0.

Prices are only marginally lower than under the Liddell exit scenario – from 2024-26 prices are on average $2.90/MWh lower in NSW while the impact is also marginal in other states. The price reductions are offset by reduced investment in peaking gas, pumped hydro and wind than would be assumed to occur in the exit scenario.

Demand reduction

The demand reduction scenario assumes a drop of 950MW that would more than offset the impact of the exit of Liddell, with prices staying relatively flat after 2020 reflecting that the market remains competitive.

Under this scenario the need for 500MW of NSW gas peaking capacity is reduced, along with a fall in new gas peaking capacity in Victoria by 280MW, while uncommitted NSW wind farm investment after 2025 is expected to be 1000-2000MW lower.

[i] The Underwriting New Generation Investment program announced by the Federal Government

[ii] Report of the Liddell Taskforce, April 2020

[iii] The EEP provides grant funding to assist with the development of large-scale electricity and storage projects in NSW.

Related Analysis

The return of Trump: What does it mean for Australia’s 2035 target?

Donald Trump’s decisive election win has given him a mandate to enact sweeping policy changes, including in the energy sector, potentially altering the US’s energy landscape. His proposals, which include halting offshore wind projects, withdrawing the US from the Paris Climate Agreement and dismantling the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), could have a knock-on effect across the globe, as countries try to navigate a path towards net zero. So, what are his policies, and what do they mean for Australia’s own emission reduction targets? We take a look.

A farewell to UK coal

While Australia is still grappling with the timetable for closure of its coal-fired power stations and how best to manage the energy transition, the UK firmly set its sights on October this year as the right time for all coal to exit its grid a few years ago. Now its last operating coal-fired plant – Ratcliffe-on-Soar – has already taken delivery of its last coal and will cease generating at the end of this month. We take a look at the closure and the UK’s move away from coal.

Retail protection reviews – A view from the frontline

The Australian Energy Regulator (AER) and the Essential Services Commission (ESC) have released separate papers to review and consult on changes to their respective regulation around payment difficulty. Many elements of the proposed changes focus on the interactions between an energy retailer’s call-centre and their hardship customers, we visited one of these call centres to understand how these frameworks are implemented in practice. Drawing on this experience, we take a look at the reviews that are underway.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.