Cobalt: Could it be a brake on battery development?

Recent media reports[i] have debated whether government should support the development of electric vehicles (EV) given their current costs. Part of the discussion has focussed on the cost of the all-important power source, the batteries. Lithium-ion batteries are core to many EVs, and a vital component in these batteries is cobalt. With projections that the development of EVs is expected to accelerate[ii] , this has prompted some concern about whether the world will have an adequate supply of cobalt into the future[iii].

Cobalt in the energy industry

Cobalt is a key component used in the cathode section (the negatively charged pole of the battery) of rechargeable batteries, usually stored as the compound lithium cobalt oxide. It has a wide range of uses within the energy industry and plays a vital role in the storage of energy in rechargeable batteries - from mobile phones to home and utility-scale batteries (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Products powered by cobalt

Source: Global Energy Metals Corporation

Source: Global Energy Metals Corporation

Cobalt has an essential role in the magnets required to produce energy from wind turbines and as a catalyst for the process of biogas production[iv]. Cobalt was also at the core of the widely publicised “World’s Largest Battery” now operating in South Australia.

Although it is difficult to assess the likely level of future demand for large-scale rechargeable batteries for grid supply, it is expected to grow and with it demand for cobalt.

Figure 2: Uses of cobalt in industry

Source: Battery University

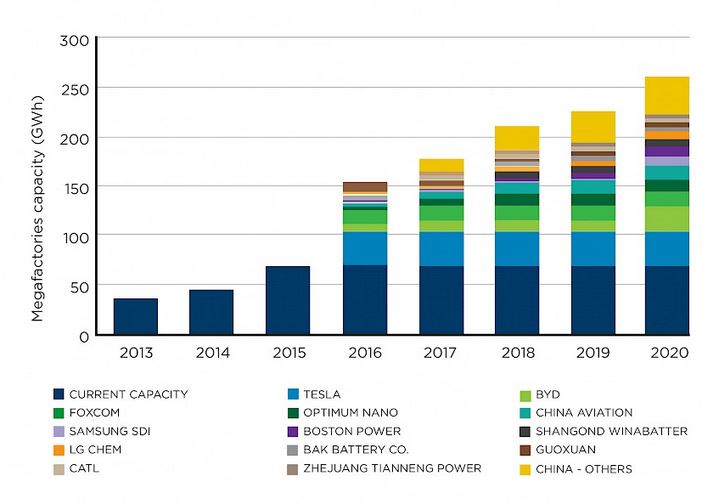

In 2015 the total global supply of cobalt was 100,000tpa and the battery market consumed 48,000tpa[v]. In October 2016, Benchmarked Mineral Intelligence (BMI) tracked 14 lithium ion mega factories under construction with 3-25GWh capacities, and estimates cobalt demand will regularly exceed 100,000tpa by 2020.

Cobalt price fluctuations

At the end of 2017, the global cobalt price sat at US$72,000 per tonne and had reached US$80,000 per tonne by January this year – up from a record low of US$22.000 in February 2016 and an increase of more than 341 per cent increase[vi].

Figure 3: Global cobalt prices 2011 - 2017

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

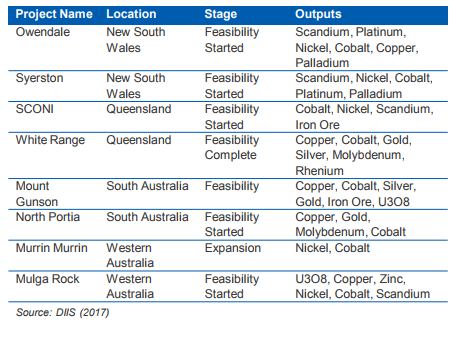

The Australian Department of Industry, Innovation and Science has highlighted eight cobalt mining projects in Australia – seven in feasibility phases and one in expansion phase – demonstrating the market’s expectation of an exponential growth in cobalt demand.

Figure 4: Australian cobalt projects

Improving cobalt efficiencies in batteries

While much of the discussion surrounding a potential cobalt shortage focused on the expected growth in the number of EVs on our roads, there will be an increasing use of rechargeable batteries to support renewable generation development, home battery storage solutions and industrial scale-utility batteries for grid support. Developers of batteries are considering other options to reduce their need for cobalt.

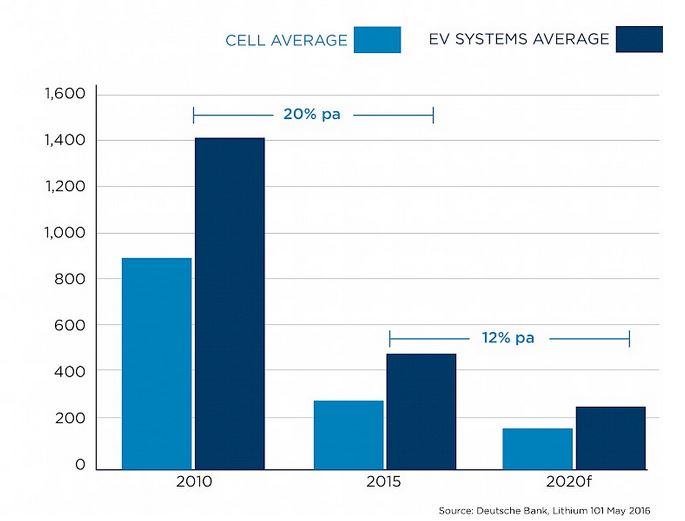

Fortune magazine reports that Tesla has opted for a lower density cobalt battery requiring approximately half the amount than a traditional lithium battery. A traditional Nickel Manganese Cobalt (NMC) composition of a lithium battery cathode is around 33 per cent cobalt. New, more energy dense technologies, such as Tesla’s Nickel Cobalt Aluminium (NCA) lithium preference is 15 per cent cobalt.

Battery manufacturers are starting to play with the relative proportions of nickel, cobalt and manganese. BMI states that batteries have moved from a 1-1-1 ration to a 5-2-3 ratio, with more nickel and the industry is looking to an 8-1-1 ratio[vii].

Global Energy Metals’ outlook on the use of cobalt in batteries suggests that industrial consumption is growing, while average battery prices are dropping and cobalt battery demand is driving further efficiencies, such as Tesla’s NCA technology. Nonetheless Cobalt’s limited availability as a finite resource highlights a potential brake on the ongoing broader development of rechargeable batteries, in their current technological state, for the industrial energy market.

Figure 5: New battery capacity

Source: Global Energy Markets Corporation

Source: Global Energy Markets Corporation

Figure 6: Battery costs are falling

Source: Global Energy Markets Corporation

Source: Global Energy Markets Corporation

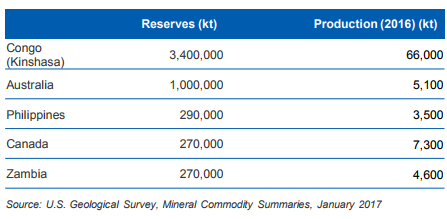

Risk of cobalt’s global supply chain

The current supply chain for cobalt is also a key industry risk, with the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) being the dominant global market supplier of cobalt. R3D estimates in 2015, 60 per cent of the world’s supply of cobalt originated in the DRC.

The DRC is a key player in global cobalt production because it is the sole three tier supplier cobalt producer, with pure cobalt mining, cobalt by-product from nickel mining and cobalt by-product from copper mining.

Figure 7: Top five cobalt mine reserves

Given the limited supplier options for cobalt, in October 2017, the Financial Times[viii] reported that Volkswagen attempted to secure a minimum five-year supply at a fixed price, while other car manufactures such as BMW and Tesla also tried to secure stocks. This shined a light on the current and growing cost and supply issues facing car manufacturers to meet the requirements of a growing EV market.

In contrast to this reliance on cobalt, the Resources and Energy Quarterly report highlights that technology change is just as likely in future years, to render cobalt based battery technologies nascent, or heavily reduced in their usage of cobalt.

[i] The Australian, 29 January 2018 “Drive for subsidies weak”; The Australian, 30 january 2018, “Muddled EV plans drive us towards a Cuban sunset”

[ii] https://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/GlobalEVOutlook2017.pdf

[iii] Financial Times, 17 October 2017 “Cobalt stand-off key to future of electric vehicles”

[iv] https://www.cobaltinstitute.org/renewable-energy.html

[v] http://benchmarkminerals.com/do-drc-politics-spell-further-price-rises-for-cobalt-why-19-december-is-a-date-to-mark/

[vi] https://tradingeconomics.com/commodity/cobalt

[vii] https://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/the-truth-about-the-cobalt-crisis#gs.iFSLJkc

[viii] Financial Times, 17 October 2017 “Cobalt stand-off key to future of electric vehicles”

Related Analysis

The return of Trump: What does it mean for Australia’s 2035 target?

Donald Trump’s decisive election win has given him a mandate to enact sweeping policy changes, including in the energy sector, potentially altering the US’s energy landscape. His proposals, which include halting offshore wind projects, withdrawing the US from the Paris Climate Agreement and dismantling the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), could have a knock-on effect across the globe, as countries try to navigate a path towards net zero. So, what are his policies, and what do they mean for Australia’s own emission reduction targets? We take a look.

UK looks to revitalise its offshore wind sector

Last year, the UK’s offshore wind ambitions were setback when its renewable auction – Allocation Round 5 or AR5 – failed to attract any new offshore projects, a first for what had been a successful Contracts for Difference scheme. Now the UK Government has boosted the strike price for its current auction and boosted the overall budget for offshore projects. Will it succeed? We take a look.

Battery Storage: Australia’s current climate

As the world shifts to renewable energy, the importance of battery storage becomes more and more evident. Intermittent sources of generation – wind and solar – are playing an increasing role during the transition, and as dispatchable plants leave the market, battery storage, along with pumped hydro and gas-fired generation, will become more critical to the grid. So, what does Australia’s storage capabilities look like, and what will be needed to meet our net zero targets? We take a look.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.