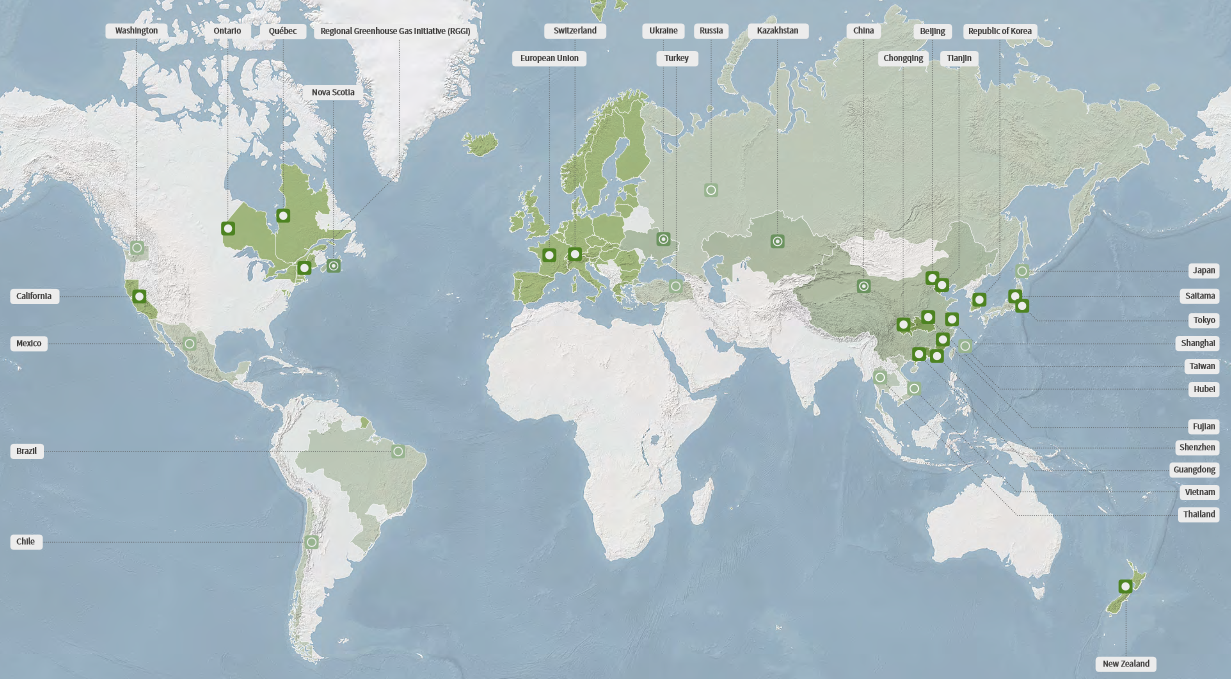

Carbon schemes around the world

It was recently reported that China will launch a national emissions trading scheme (ETS) by the end of 2017[i]. The nation has experimented with several schemes since 2013, with varying levels of success, and by the end of the year will join other major economies by introducing a national ETS.

By the end of 2017, the world’s ETS programs will regulate more than seven billion tons of greenhouse emissions, with 19 systems operating across the globe. They will operate in economies that generate almost half of the world’s gross domestic product and cover more than 15 per cent of global emissions[ii].

We take a look at the energy policies of some of the world’s biggest emitters.

Figure 1: ETS World Map

Source: Emissions Trading Worldwide, International Carbon Action Partnership Status Report 2017

Carbon policies

At its essence, a carbon policy in the electricity sector has the aim of reducing emissions from the sector. This can be done in several ways. Generally, to reduce emissions the uptake of new, lower emissions technology is needed. This can be encouraged by either subsidising the incumbent generation or increasing the price of the higher emissions technology - or a combination of both.

Some policy options to achieve reduced emissions from electricity include but are not limited to:

- Carbon price

- Emissions intensity scheme

- Renewable energy target

- Renewable energy feed-in tariffs

- Forced coal closures

These policy mechanisms all aim to do the same thing using different regulations or market forces, and allow different energy providers to compete to ‘abate’ their emissions in the most efficient and cost-effective way.

In general terms the more market based the policy, the more cost efficient the end result will be. Market based schemes are far more efficient than traditional ‘command and control’ regulation because market forces enable polluters to find the cheapest way to reduce or off-set emissions.

An ETS - or cap and trade - creates a market of supply and demand. Industries with low emissions can sell their extra allowances to larger emitters, establishing a market price for greenhouse gas emissions. An ETS also caps the total level of greenhouse gas emissions to help ensure that the required emission reduction occurs.

Europe

The European Union (EU) has an EU wide emissions policy and, until the implementation of the Chinese national ETS, is the largest emissions market in the world covering 31 countries (28 EU countries plus Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway).

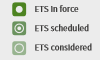

Figure 2: Overall EU greenhouse gas emissions

Source: Emissions Trading Worldwide, International Carbon Action Partnership Status Report 2017

The ETS covers over 11,000 stationary sources of emissions, namely power stations and large scale manufacturing and air travel between the countries. The scheme currently covers 45 per cent of the EU’s greenhouse emissions.

Through a cap and trade scheme, the total amount of greenhouse gas emissions from the sources covered by the EU emissions trading scheme is capped at certain amount. The EU aims to reduce this total by 20 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions by 2020, at least 40 per cent by 2030, and 80-95 per cent by 2050, when compared to the region’s 1990 levels[iii]. Within this cap, participants in the scheme can buy and sell permits as they wish. The allowances to emit act like a currency within the scheme and their limited amount give them a value.

New Zealand

New Zealand has a national ETS (NZ ETS) that requires all sectors of New Zealand’s economy to report on their emissions and, with the exception of pastoral agriculture, to purchase and surrender emissions units to the Government for those emissions. Just over half of New Zealand’s greenhouse gas emissions are covered by NZ ETS surrender obligations[iv]. The scheme also enables sectors that decrease emissions, such as planting trees, to sell credits to emitters.

New Zealand’s overall greenhouse gas target is a five per cent reduction from 1990 levels by 2020, a 30 per cent reduction from 2005 levels by 2030 (equivalent to 11 per cent reduction from 1990) and a 50 per cent reduction from 1990 levels by 2050.

The eligible emissions unit is the New Zealand Unit (NZU). A unit equals one metric tonne of carbon dioxide, or the carbon dioxide equivalent of any other greenhouse gas. A schematic of how the scheme is administered is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Simplified illustration of NZU trading

Source: NZ Ministry for the Environment

United States

The United States does not have a national ETS, but it does have two regional schemes.

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) commenced in 2009 and is a cooperative between nine states: Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Rhode Island and Vermont. It is the first mandatory ETS in the United States.

Each state's CO2 Budget Trading Program limits emissions of CO2 from electric power plants, issues CO2 allowances and establishes participation in regional CO2 allowance auctions. States sell emission allowances through auctions and invest proceeds in energy efficiency, renewable energy, and other consumer benefit programs, to increase jobs and innovation in the clean energy sector.

California also has its own cap and trade scheme. Québec and California have been operating their programs, since 2012 and 2013 respectively. Both programs belong to the Western Climate Initiative, and the states linked their programs in 2014.

On 22 September 2017, California, Québec and Ontario agreed to extend the existing link of the California and Québec cap and trade programs to also include Ontario. The agreement will come into effect on 1 January 2018. The three states have climate policies to decrease their overall emissions by at least 35 per cent compared to 1990 by 2030.

Asia

Cap and trade is becoming increasingly more established in Asia. Tokyo initiated its cap and trade program in 2010, Korea’s national carbon trading market commenced in 2015, while China plans to start a nationwide ETS at the end of 2017. These nations have also commenced early-stage discussions and are looking towards possible future cooperation.

South Korea

In 2010 South Korea legislated the Framework Act on Low Carbon and Green Growth. A small number of large companies were responsible for more than 60 per cent of the nation’s emissions, so the government introduced the Target Management Scheme (TMS) in 2012, which set reduction targets for individual companies. The TMS operated successfully, but did not allow for emissions trading. In January 2015, the Korean ETS (KETS) was launched.

To support the Paris Agreement, Korea set a 2030 target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 37 per cent from business-as-usual levels[v]. By the end of 2015, there were a 525 companies participating in the KETS.

Japan

The Japanese Voluntary Emissions Trading Scheme (JVETS) was introduced in September 2005 to support emission reduction activities by Japanese companies. JVETS was a voluntary cap and trade system, which concluded in 2010. In December 2010 the Japanese government postponed plans for a national ETS.

Tokyo’s cap and trade scheme for large scale business facilitates launched on 1 April 2010. It is Japan’s (and Asia’s) first mandatory ETS, and was set by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. It has seen a large reduction in emissions.

Large facilities are covered by Tokyo’s cap and trade scheme, while emissions from small and medium‒sized facilities are covered by the Tokyo Carbon Reduction Reporting Program, which requires facilities to account for their emissions and encourages them to implement their own low-carbon measures. Both programs aim to help Tokyo to achieve its goal of reducing CO2 emissions by 30 per cent by 2030 compared to 2000 levels.

Figure 4 shows that reductions made in the first compliance period of the program (FY2010-2014) are approximately 14 million tons over five years, the equivalent of five years’ worth of CO2 emissions from 20 per cent of Tokyo’s total households[vi]. This was achieved even with an increase in the size of covered facilities – in the 2014 financial year there was a one per cent size increase when compared to the previous year, and a four per cent increase when compared to the base year.

Figure 4: Changes in total CO2 emissions of covered facilities in Tokyo

Source: Emissions Trading Worldwide, International Carbon Action Partnership Status Report 2017

Mexico

The Mexican carbon tax is primarily applied to gasoline and diesel emissions. The Mexican government is investigating the compatibility of a future ETS with the current carbon tax and The Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT) is examining ways to achieve a more efficient carbon pricing.

In August 2016, SEMARNAT and the Mexican Stock Exchange signed a Memorandum of Understanding to implement an ETS Simulation Exercise for private and public sectors, so far 50 companies have confirmed their participation in the program.

The objectives of the exercise are to[vii]:

- Promote dialogue among stakeholders;

- Build capacity for ETS operation in facilities and companies, as well as in government and regulatory bodies; and,

- Learn lessons from the simulation to help policymakers design the ETS regulations.

SEMARNAT aims to publish a draft ETS regulation by 2018, building on the lessons learned from the ETS Simulation Exercise and from international collaboration.

Australia

The debate around carbon policy has reignited in Australia with the release of the Finkel review in June as well as the recent debate surrounding the future of coal-fired power stations and the implementation of a clean energy target (CET). Finkel himself suggested a CET to fix the energy policy vacuum that has left us with a fragile national energy market and soaring wholesale prices.

The example of what other countries are doing to curb their electricity emissions might provide some guidance on the way forward for Australia, but whatever policy is used, the importance of stable, predictable policy is imperative.

[i] Australian Financial Review, 3 October 2017, p6

[ii] Emissions Trading Worldwide, International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP) Status Report 2017 https://icapcarbonaction.com/en/?option=com_attach&task=download&id=447

[iii] European Commission, Climate Action, https://ec.europa.eu/clima/citizens/eu_en

[iv] New Zealand Ministry for Environment, http://www.mfe.govt.nz/climate-change/reducing-greenhouse-gas-emissions/about-nz-emissions-trading-scheme

[v] Emissions Trading Worldwide, International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP) Status Report 2017

[vi] Emissions Trading Worldwide, International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP) Status Report 2017

[vii] Emissions Trading Worldwide, International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP) Status Report 2017

Related Analysis

International Energy Summit: The State of the Global Energy Transition

Australian Energy Council CEO Louisa Kinnear and the Energy Networks Australia CEO and Chair, Dom van den Berg and John Cleland recently attended the International Electricity Summit. Held every 18 months, the Summit brings together leaders from across the globe to share updates on energy markets around the world and the opportunities and challenges being faced as the world collectively transitions to net zero. We take a look at what was discussed.

Great British Energy – The UK’s new state-owned energy company

Last week’s UK election saw the Labour Party return to government after 14 years in opposition. Their emphatic win – the largest majority in a quarter of a century - delivered a mandate to implement their party manifesto, including a promise to set up Great British Energy (GB Energy), a publicly-owned and independently-run energy company which aims to deliver cheaper energy bills and cleaner power. So what is GB Energy and how will it work? We take a closer look.

Delivering on the ISP – risks and opportunities for future iterations

AEMO’s Integrated System Plan (ISP) maps an optimal development path (ODP) for generation, storage and network investments to hit the country’s net zero by 2050 target. It is predicated on a range of Federal and state government policy settings and reforms and on a range of scenarios succeeding. As with all modelling exercises, the ISP is based on a range of inputs and assumptions, all of which can, and do, change. AEMO itself has highlighted several risks. We take a look.

Send an email with your question or comment, and include your name and a short message and we'll get back to you shortly.